About halfway through my university life, not long after the freshman euphoria finally lost its magic and was immediately replaced by a heavy chain of events that was slowly weighing me down, I desperately needed change. I eventually decided to go against my introverted nature and threw myself into various activities that ranged from organizing welcoming events for newly enrolled students to taking photos of on-campus cultural events. The most interesting experience, however, was when I worked as a writing tutor – which is just a fancy way of saying that I was an essay checker.

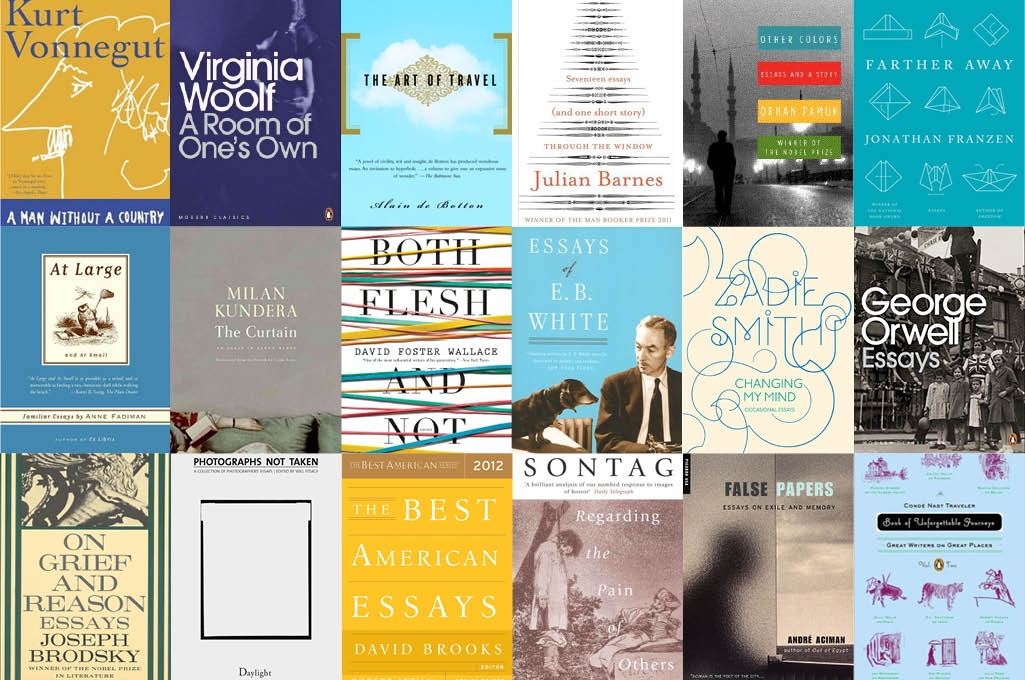

“Make sure there are enough references!” was my supervisor’s favourite reminder. The first time he said it, I did not understand why it was such a big deal. Aren’t essays supposed to be based on a person’s opinions? But I did as I was told, and always made sure that everyone’s essay cited other works. After more than a year of annotating pages and pages of essays, I noticed that the best ones included the writers’ own perspectives neatly mixed with the writings of experts regarding the topic at hand. My supervisor’s advice made sense. Not long after this enlightenment, I quit the job, and plunged into an ongoing obsession with the essay form – particularly the personal essay.

While essays are generally personal, it is the “I” that makes personal essays different from the rest. Yet despite the writer’s clear presence embodied in that one capitalized vowel, the element that makes the work personal lies elsewhere. Unlike novels, there is no room for the writer to hide. Figures of speech are used as a tool to convey opinions in a beautiful way, not as a mask. Dealing with literature that is branded as fiction is like holding a wonderfully wrapped present while quietly guessing its contents whereas reading a personal essay saves us from having to endure the pain induced by curiosity. We are immediately presented with the writer’s main ideas.

The writer’s main ideas. This is the key – not the writer; nor the idea, but the writer’s idea. In “Of Books,” Michel de Montaigne, also known as the pioneer of the personal essay, wrote, “Let attention be paid not to the matter, but to the shape I give it.” He specifically requested that his readers pay attention to the way he presents a certain topic. Montaigne refrained from using the essay to promote his identity and intelligence, and he was certainly too skillful to use it as a vessel that merely stores cold facts devoid of character and emotion.

But Montaigne’s words were written – most likely with a quill – centuries ago. It is not surprising that the personal essay has undergone changes over such an extensive stretch of time, though it is probably more reasonable to say that the increasing number of writers who have since followed Montaigne’s footsteps are the ones responsible for those changes. The casual nature of essays – as opposed to the discipline demanded by serious poetry and commitment required by novels – grants writers a space to speak about things that matter to them without being haunted by rules. This advantage is also its disadvantage because writers can always get a little too comfortable that they end up drowning in self-indulgence. No matter. No shape. Just an uppercase “i” too busy with itself.

In a piece featured on The New Republic entitled “The New Essayists, or the Decline of the Form?” Adam Kirsch laments over the growing population of essayists (or writers who think they are essayists, as I imagine Kirsch would say) too focused on the Self. He points out that although the self “has always been at the heart of the literary essay,” a lot of what readers would stumble upon these days are “exclusively about the self, with the world serving only as a foil and an accessory, as a mere staging ground for the projection of the self.”

As an avid reader of personal essays and essays in general, I sympathize with Kirsch. I, too, worry that future generations will not be able to pick up numerous essays written during this critical period and not feel the amazement I do each time I read pieces from Montaigne’s time. As someone who writes essays, I am even more worried because I dread that I am doing something wrong, or not doing something right enough. Am I a part of the group Kirsch so eloquently criticized? I wonder. Sometimes the thought even keeps me up at night.

But as an essayist himself, Kirsch is hopeful. He brought up a point that I have already pieced together through my supervisor’s helpful advice and a year of scribbling in the margins of many essays. “Not coincidentally, some of the greatest essays, from Addison on Paradise Lost to Mill on Coleridge, are engaged with texts, which is to say, with other minds,” wrote Kirsch. To put it simply, an essayist’s ally is another essayist.

I do not see Adam Kirsch’s tip as a threat towards the freedom promised by the personal essay. I am still optimistic about the personal essay in that it allows the writer to play the role of a potter who spends his or her days trying to make the perfect cup. Two potters who mold the same amount of clay in the same room will not produce identical things – one might prefer a cup while the other a bowl. But by catching a glimpse of each other’s techniques, both will learn a thing or two.

This cup is done. Thank you, Montaigne and Kirsch.