During my free time, I enjoy visiting bookstores. But since the price of imported books in Jakarta are not exactly financially friendly, I usually end up hanging around the fiction section – shamelessly taking my time to read random paragraphs from various new releases, comparing fonts and paper quality, or my ultimate favourite pastime: smiling at the exaggerated blurbs on the back covers of bestselling novels.

It was not until a few weeks ago that I realized how incredibly safe my habits had been. I had grown too sure of my own interests that I rarely ventured out of my comfort zone, which in this case is a mix of fiction and creative non-fiction – a discovery that comes as a shock to me for two reasons. First of all, it is now clear to me that I have been delusional about the scope of my literary obsession, and secondly, I am forced to accept the power of categorization. As much as readers hate to admit it, genres are the devils that divide the literary world.

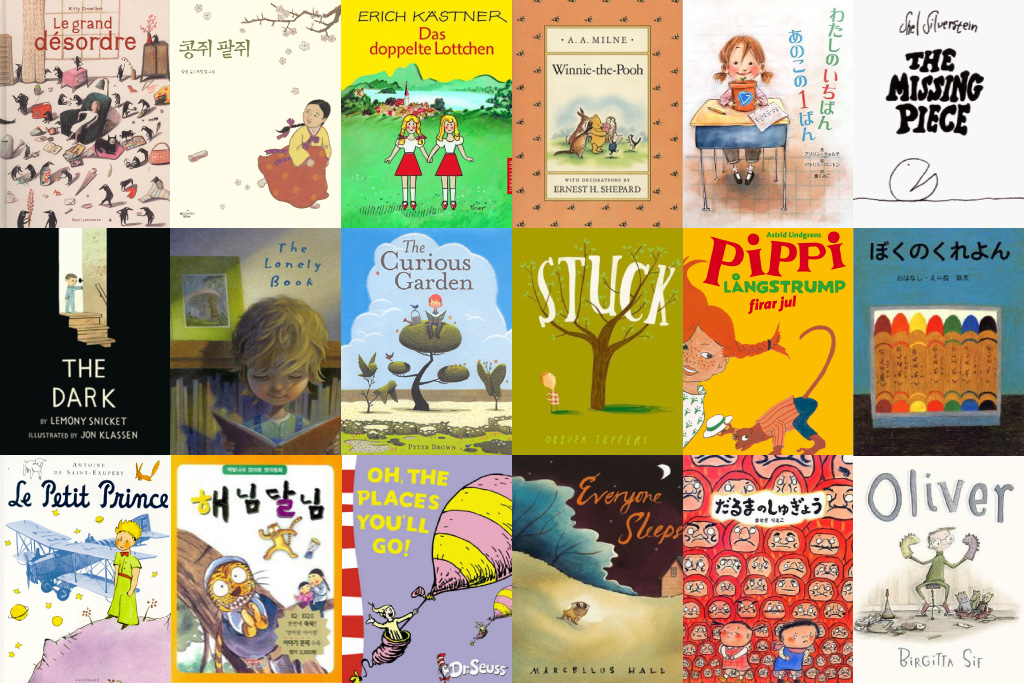

In the attempt to break free from my usual routine, I decided to browse the children’s literature section of the generously air-conditioned bookstore I recently visited after work. I suddenly became extremely aware of the impact of genres. Labeled as “children’s books,” the titles that I used to love all those years ago turned into gems that are no longer within my reach. It felt as if I had lost the right to pick up classics by Roald Dahl or Maurice Sendak.

But have we really lost that right, or are we consciously denying it? Are we so preoccupied with the multiple complexities of our current professional and personal lives that we have lost the ability to see the value of simplicity that is commonly found in children’s books?

Oliver Jeffer’s The Day the Crayons Quit made me so happy that I decided to read all of his other books. Not only did they bring out my inner child, but they also reminded me of the years I had so few words to make sense of the world.

Has our improved command of language made us suspicious towards simplicity? Have we become seduced by intricate prose because it appears to promise us so much meaning? It is strange that we seem to be put off by things that can be easily digested. We do not trust simplicity because we want to believe that there is so much more than meets the eye. Language is one way to manipulate the quantity of reality. What can be said in one sentence in a children’s book might take up a paragraph, or even an entire chapter, in a book for “grown ups.”

It is such an irony that knowing more words leads to more problems instead of more solutions. More ironic still is that on occasions when we do decide to get fancy with our choice of words for positive reasons, the essence of the message gets lost.

In his poem entitled “Tear It Down,” Jack Gilbert wrote, “We must unlearn the constellation to see the stars.” To recover the fundamental elements of our personal realities, we have to learn how to see through the tangled web of our accumulated experiences. I believe that authors of children’s books have the answer to retrieve those elements, but because the label of “children’s books” does such a great job at excluding readers who are not children, that magical answer remains inaccessible to those who actually need it.

By considering “children’s literature” as a separate genre, we are indirectly reducing its literary worth. It is as if we are saying that the books that fall into this particular category do not deserve to be taken seriously because of the simplicity of their content. What we need to remember is that not all works of literature are comparable – not because one is more superior to the other, but because they are simply incomparable. Each work needs to be appreciated according to what it has to offer.

But perhaps I am starting to complicate this essay. So before I defeat my own purpose, I have to come to a conclusion. I believe that everything there is to know about life can be found in those heartfelt picture books we have fond memories of but nevertheless are not compelled enough to revisit. Why should we crave for complexity if what we truly want lies in the creative simplicity of a Dr. Seuss riddle?