A Match of Wits

Ken Jenie introduces one of his favorite forms of competition.

by Ken Jenie

From Kool Moe Dee and Busy Bee challenging each other in moving a crowd, Jay-Z and Nas trading insults on songs, to most recently Kendrick Lamar declaring himself the king of New York, competition has always been and continues to be one of the driving forces behind hip hop music. With an emphasis on how clever, how cool, how original, and how credible emcees are, hip hop musicians inadvertently refine their craft within the established parameters as well as explore new and exciting territories the genre has yet to touch upon through competition. Emcees continually test their skill against each other, and this tradition of battling has become a byproduct, which, in recent years, has become organized into leagues and has given birth to a slew of stars within its pocket of hip hop.

Although in terms of relevancy I believe battling has not reached its full potential, it has gotten a significant amount of attention with popular individuals such as Jay-Z, Deadmau5, Drake, and Eminem (who himself is a graduate of the battling scene), publicly referring to battles and battlers (P Diddy even sponsored one of the biggest battling events in recent years through his vodka label, Ciroc). This popularity, of course, wasn’t always the case.

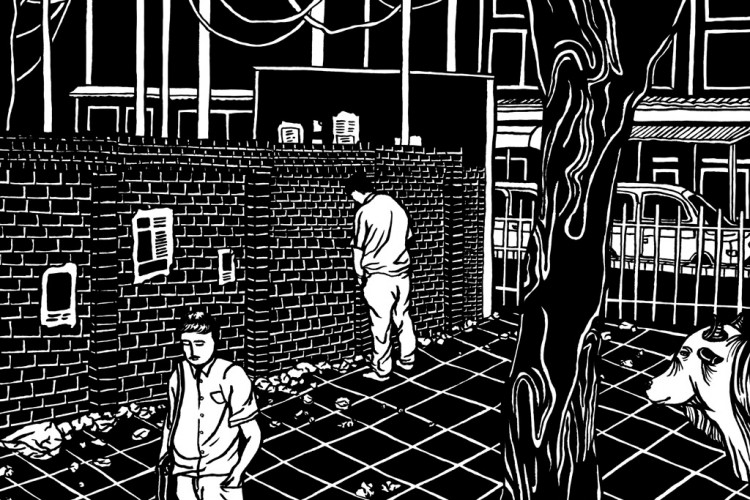

As mentioned before, competition has always been a part of hip hop, with battles happening everywhere from stages, street corners to school lunchrooms. The head to head format quickly gained momentum. The 90s and early 2000s was a time when battling established itself as a legitimate subgenre of hip hop, with events specifically catered to emcee competition gaining momentum, most famously with the freestyle battles of Scribble Jam and Rocksteady MC Battle, as well as Smack DVDs recording and distributing via the mixtape circles, emcees going head to head in various locales. During this period, mainstream media attempted to assimilate battling into their programs (MTV, MTV2, HBO, BET) but relatively none successfully made it a consistent primetime venture, most discontinued their production, and the longest continuing series of battles in BET’s 106 and Park still being a small, sideshow segment (to their credit, 106 has recently attempted to adapt the new format of battling into its programming).

Despite the lack of mainstream relevancy, organizers continued to create events to accommodate battles, and the rapid development of technology gave them new avenues to promote their events. Youtube is one of the critical factors in the development of modern-day battling. This video sharing website became the stage to showcase battles and, until today, is the premier media to watch them. First starting with users posting footage of past battles, the first well known series of battles using Youtube as its medium were made by a UK media, JumpOff.TV. Organizing a “World Rap Championship”, JumpOff gathered emcees from around the globe to battle in a 2 on 2 format. Other Youtube-using leagues started to get traction, and through the successes of organizations such as Grindtime (which at some point was the most famous league), Ultimate Rap League (URL), King of the Dot (KOTD), Don’t Flop, and Ultimate Warrior (UW) the current model for battling was born. The current leagues would create a live event and then document the battles with the specific intent to publish it online.

Now, what is battling like at the moment? To keep it simple, a typical battle consists of emcees taking turns berating each other in accapella with prepared material (more popular in the past were freestyle battles where rappers were expected to create clever rhymes on the spot). They would usually already know who their opponents are prior to the event and have adjusted their writing to them. Broken down into 3 rounds, each round has an allotted time for the emcees to perform their material. Sometimes the battles are judged by a panel, but most of the time it is left for us viewers to personally decide the victor.

Like mixed martial arts or boxing matches, the enjoyment in battles lies in witnessing competitors skillfully break each other down (though, admittedly, I enjoy watching neither mixed martial arts nor boxing, which I suppose gives me no authority to make this statement… shucks). The big difference between battles and most sports is the subjectivity involved in deciding a winner – this is one of its most interesting aspects, as one’s measure of a performance could be juxtaposed to a public consensus.

There are two major elements that are usually considered when watching battles – the material emcees are rapping and their showmanship. Some things that could be personally judged when listening are how intricate the rhyme structure are, how well the concepts and words are put together, how original the ideas are, how relevant their material to their opponent is, and how credible the things the emcee is saying are. As battling are performances that take place most often in front of a live audience (and later a home audience), their showmanship plays a factor. Everything from how well they deliver their written material, how well they engage the audience (both live and at home), how animated they are, how believable they are (a pre-teen suburban kid wearing a private school uniform and rockin’ a comb over will probably not be believable if he/she decides talks about slinging crack at a trap and totting M16s) to their physical appearance matter. Each person watching have their own preference, and as battling is a game of perception, if an emcee can convince you he is better, than you will most likely declare him the winner.

There are multiple elements in battling that may perhaps dissuade people from enjoying them. The content is often violent, homophobic, misogynistic, racist – generally politically incorrect. The reason behind this, of course, goes beyond the realm of battling. The content reflects our societies own views concerning these subjects. Not to say that an emcee is not accountable for his/her proclamations, but to establish the fact that violence, homophobia, misogyny and racism are problems that go beyond the realm of battling. As battling involves verbally attacking individuals (with, more often than not, a good dose of machismo), these are themes that are often used to discredit opponents.

It should be known that there have been plenty of battles that did not use the subjects mentioned as ammo (there have been contests where simply discrediting opponents lyrical abilities or their choice of clothing winning battles). There is also a common understanding that most of the competitors do not really mean what they say so do try to digest their blurb with a grain of salt (many emcees would be serving multiple life sentences if they really have shot people as many times as they say they have). Battling is a game of dishing out insults, though, so be prepared to hear things that might offend you.

Emcee battles is a subgenre all everyone, especially hip hop enthusiasts, should take a look at. Competitive in nature, emcees constantly raise the bar for lyricism and performance, so as time go on the battles gets better and better. With internet video becoming its main avenue for promotion, leagues cater their productions to the medium, and gives us high-quality entertainment we can enjoy freely from the comfort of our homes. A game of insults, some of its content might not be easy to digest, but at the end of the day it is really a match of wits.