When we willingly uproot ourselves from our comfort zone for the sake of experiencing something new, there are, I believe, two possible outcomes. This is true for both travellers and migrants. The first is quite positive in nature – even if it may generate its own set of problems in the long run – that is, being so absorbed in the new environment that the situation back home seizes to offer any form of solace. We fear the impending departure and the great loss that will immediately follow it; so nostalgic sentiments will begin to seep through our mental resistance to leave. The second outcome is comparatively more disappointing, albeit from a different angle. As opposed to the traveller who does not wish to return home, travellers experiencing this situation want to do nothing but return home. Perhaps certain expectations have not been met or on the contrary, everything is exactly as expected, completely devoid of surprises.

The latter scenario reminds me of Jamaica Kinsaid’s “Poor Visitor,” a short story about a woman who left her home country to start over abroad. In the early stages of the character’s new life, she lamented, “The Atlantic Ocean stood between me and the place I came from, but would it have made a difference if it had been a teacup of water? I could not go back.” While it is important to note that the context here cannot be applied to the idea of “travelling” discussed throughout this essay series, there is a connection that I think is worth acknowledging. At some point, the traveller will come to the realization that he or she somewhere else. It is not the measurable distance between the two points that has become so unsettling, but the fact the decision to establish that distance had already been made. “I could not go back” could mean more than a straightforward declaration of having no means to go home as it could also imply that the traveller could not go back until the journey has been completed. The journey has become a symbol of self-determination and pride.

Travel will replace those you leave behind,

Tire away for true pleasures are found through duress.

I have seen that stillness corrupts

In movement water sweetens, and without it, stagnates.

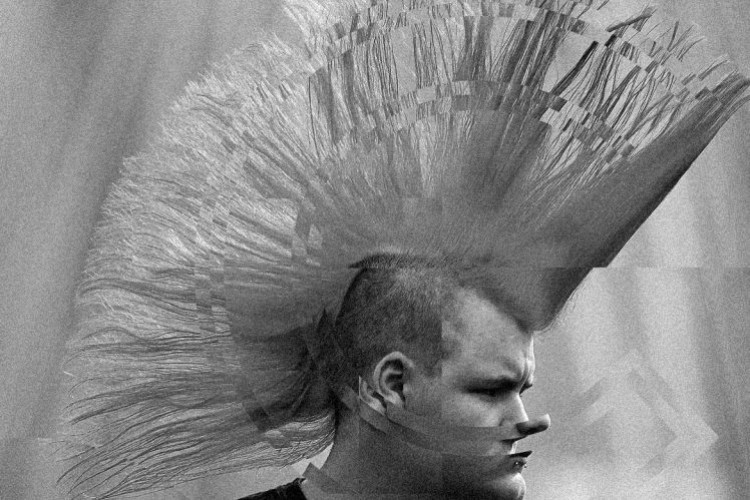

There is a great deal of pride, if not conviction, in the lines of Diwan of Imam Al-Shafi’i’s poem (translated by Ahmad Diab). But it is not baseless pride. It is not merely a statement of resisting our temptation to give up so easily; it is a reminder: as humans, we have an obligation to uproot ourselves. If we were to stay in a new place, only because it is overflowing with experiences the place we left no longer has in stock, wouldn’t it mean that we are surrendering to yet another form of stagnation? The first outcome elaborated in the first paragraph may be in favour of “the new” (at first), but it goes against the importance of movement. A new setting, once adopted, becomes a new version of the old repetitive cycle.

Later in the poem, Al-Shafi’i presented yet another metaphor to express his disdain for stasis: “If the Sun stood still in his sky / Mankind, east and west, would grow weary with him.” These lines imply that it is not only the traveller who needs to experience new things, but places, too, need to welcome a steady flow of new faces. There is a necessary exchange between the traveller and the places travelled to and from. Thinking about such matters following the euphoria or disappointment of a journey is often a challenge, but it is necessary. There is a great amount of learning to be done not only in the place we plan to visit or have just visited, but also in the process of travelling – of moving – itself. The following verses from Poska Ariadana’s “Gipsy” provide a fitting visualization of the relationship between those who leave and what they leave behind:

Tanah ini tak ingin membatasi

jiwa-jiwanya yang ingin pergi

kesana kemari

Seiring pagi ku akan hilang

terus menembus petang

mencari arah pulang

(This soil does not intend to limit

its souls that desire to wander

here and there

Come morning I will vanish

forever piercing through dusk

searching for my way home)

Perhaps our desire to move about in search of new places comes from our deep longing to find our true home. “Home” does not necessarily have to be our place of origin – an idea I think is highly digestible in this mobile era – it simply has to offer us a sense of belonging. The comfort of embarking on a journey lies in the traveller’s knowledge that it is temporary, and that it comes in various forms. Leaving – no matter how close or far away we intend to leave, and for how long – is difficult, but the promise of returning, and the truth that both leaving and returning are repeatable is why travelling (mentally, physically and spiritually) is ingrained in us.