Urban Studies with Marco Kusumawijaya

Athina Ibrahim (A) interviews Marco Kusumawijaya (M)

A

You once mentioned the reason you got into architecture was because you enjoyed reading the magazine Panorama and that your dad owned a workshop?

M

He was a contractor and owned a workshop with his brother. It was a metal workshop where we own a lathe and welding machine. Maybe the only one in our town at the time. I often made observation to what he does. Which probably had an influence on me.

What I remembered the most was reading Panorama and seeing a blueprint design by Frank Lloyd Wrights that was black and white.

The blueprint impressed me and the image stuck to me since.

A

With that memory embedded were you certain you would pursue architecture?

M

I remember having a conversation with my mother, I asked her, “Mom, do you like this type of house? Maybe we should make one of our own.” In actuality, maybe Frank Lloyd Wright was the one that got me into architecture. (Laughs)

A

During college years, you studied the vernacular architecture and architecture on cities? What made you decide to get into the latter?

M

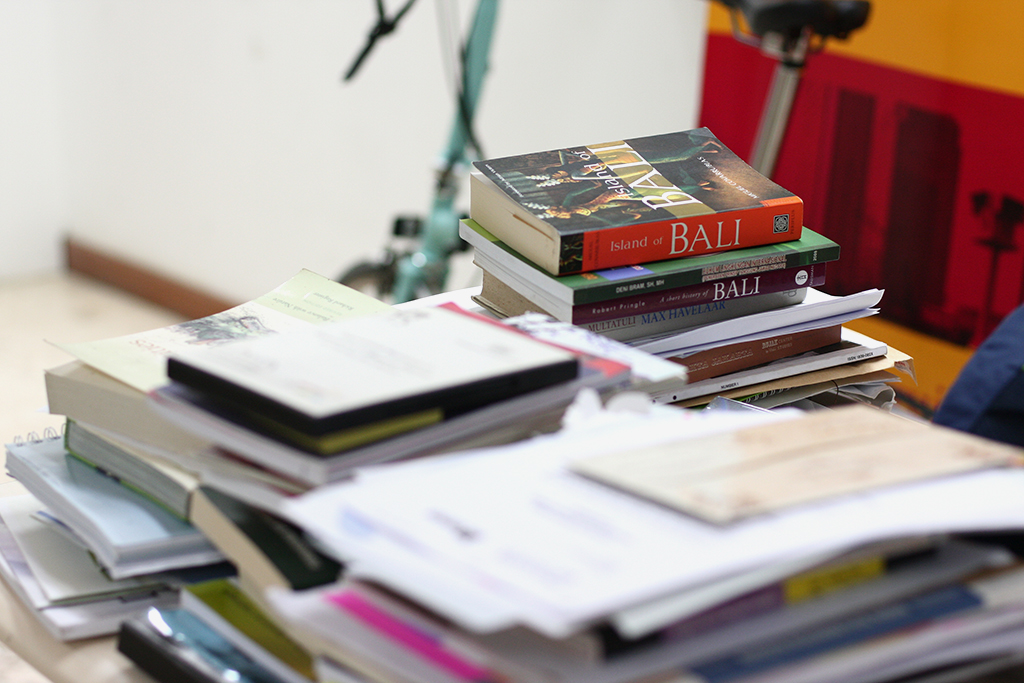

Since I entered university in the 1980s, the architecture world was branched into two worlds, the study of cities and the vernacular approach. At the time, those two disciplines became the source of inspiration. Aldo Rossi, who wrote the book ‘The Architecture of the City,’ influenced the study on cities, where she stated, “The architecture of a city is the important context from the architecture itself.”

Whereas in vernacular architecture at the time, there was a reaction towards modernism that was aiming for uniformity – architecture was not seen on the level of its society but was used asa tool for uniformity that were already spread widely in Europe.

In the 80s I was focused on both aspect, I wrote a research on vernacular architecture and had it published. My research was on East Timor and East Nusa Tenggara.

A

What made you decide to focus your research on Jakarta?

M

I studied in Belgia where people were more focused on the process of modernization. What I was interested in studying then was not limited to only Jakarta but idea of modernization.

A

Could you explain to us about your roles and responsibilities now?

M

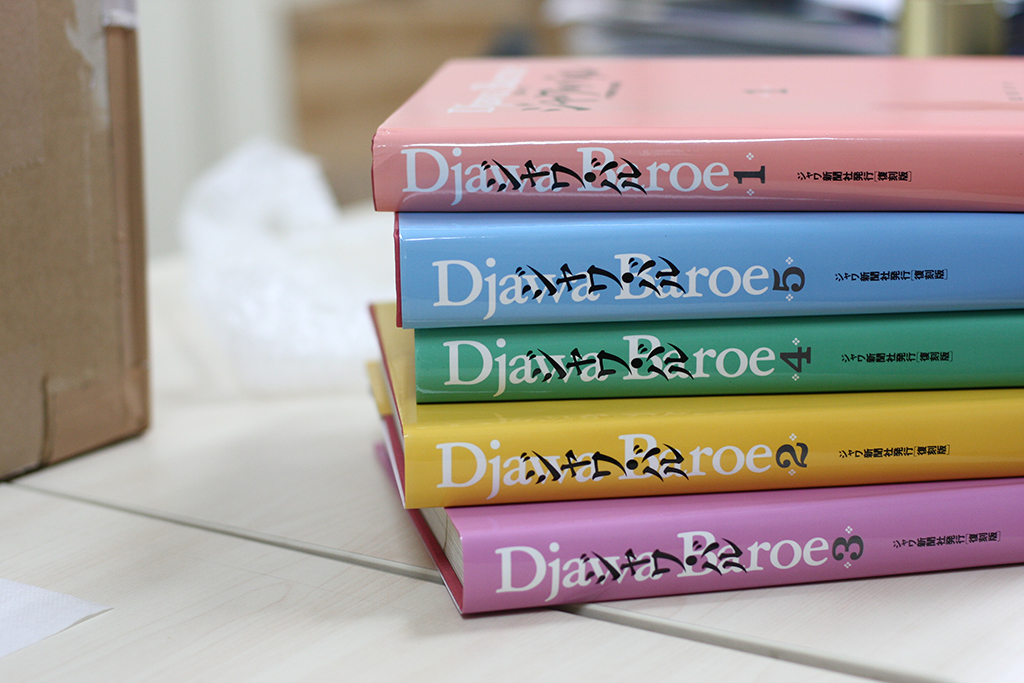

I would say I am a researcher who studies about urban planning and not an urban planner. The activities we do here in RUJAK (Ruang Jakarta) is to produce information which can be shared collectively by the communities involved. Which is why we have activities in cities as Surabaya, Makassar, and Malang which we call The Dynamics of Urban Studies (Dinamika Pengetahuan Perkotaan). We often collaborate with other groups to help people understand about the dynamics and environment about their own city. In Surabaya, there is Ayorek.org, in Makasar there is Makassarnolkm.com, in Semarang there is UGDsemarang.org.

By consistently producing information and our clear intent to collaborate, we can share our research and discussions on a wider scale.

A

With the website RUJAK running. Is there a specific audience you are targeting?

M

We want to invite as many people as possible. We produce information and are open to anyone wanting to learn about his or her city. Most urban planners do not have a full comprehension of their own city. Urban planners are very schematic. Their knowledge are often not substantial.

This lack of understanding may have stemmed from the reformation era where the knowledge of urban planning were perceived as specialist profession. There was a technocratic view that to build a city you would need someone who is an expert. And we saw the end of that era during Fauzi Bowo’s governance.

A

Are you saying urban planning does not have to be done by the experts?

M

No, I mean it should not only be done the experts. Being an expert is something very relative. Someone who resides in the city should have a proper knowledge about their own city. Those who have lived long enough in one city should be taken into consideration in talking about urban planning instead of relying on experts who is native to the city.

A

Is there such thing as an ideal city?

M

I don’t think so. You don’t build something from scratch. To develop a city is something that is on-going process. We should always remind ourself that is not in the hands of the governer to fix things. Don’t stop only because we found a good leader. A good city stems from having a good society. A good governer can be changed. A good society stays. So its best to focus on information, in the any level of the society.

I have done studies on city for almost 15 years. When I started in the 90s, only people on certain social levels were talking about urban planning. It was only within the last five years that I saw the city being talked on a larger scale. Culturist or even artists – have projected various themes of the city to their own work. Ruang Rupa as an art institution is one good example. We work a lot with art because art is one way to generate knowledge. Art is not solely about producing beautiful things, but also to produce knowledge; what people usually call the artistic way of knowing.

Photography, dance art form, writers all these art form have started to focus on the city. That is what we hope for, as long as there are more people who understands the city, it becomes an effective demand. A good leader can only be born from a demand, as long as we know what we want of a good leader, then we can demand the leader for that need of a good city.

A

Can you tell us about the concept of common space and public space in the context of Indonesia?

M

The word ‘commons’ means public property. Public is a term that is connected with the concept of the nation-state. What we call public is something that is controlled by the country while common is controlled by the community. For example, of course the easiest public place we can find is the street. If there are problems in the street, what crosses our minds must be to call the police, because the police are the representatives of a country. If we have problems with commons, for example in the scope of community, we don’t have to involve the country. So to distinguish public over commons is substantial. Sometimes we forget that nation-state is a project and communities have already existed before a country has.

There has already been the Minangnese before Indonesia. The same thing goes to Acehnese. We are actually not a country that is consisted as Indonesian nations. We are a country that is comprised of many nations, not nation tribes. “Nation tribe” refers to the idea that the tribes are the children of the nation. When talking about children, it is as if the mother has to exist first. While in this case, it is the children that existed first. Of course, now people have mixed nations, the Minangnese mix with Sundanese, etc. We could talk in Indonesian especially Acehnese. So imagine that the Acehnese are actually closer to them geographically and culturally, but they are imposed to feel closer with Manado just because they are both Indonesians. Indonesia is a construct, something that is made. This has to be realized so that we will not exaggerate it, deeming ourselves as a nation.

Now, we have to realize how the nation-state project evoked many problems, right? Corruption, etc. This project is overwhelming; we have to form the cabinet, MPR, and KPK.Whereas in the concepts of community there are many problems that could be solved on the community level. The example of an entirely state-nation that almost has no communities is Singapore, right? There, the so-called Chinese Community, Malay Community and Indian Community are very racial and culturally formalized. While here, I just want to tell that the reason why I brought up the issue about common and public again is because there are some things that we could handle ourselves. But for that, we have to realize that a state-nation – in this case, the Republic of Indonesia is something that we made, and because it is something that we made, we can change it anytime.

A

Do you have any collaborations with particular institutions in the nearest future?

M

Now, we’re having an announcement regarding a movie scenario writing competition; movies about disaster education. You can see it on Rujak’s website. The registration closed on last 24th. And then, there will be a workshop. Out of all the people who registered, the chosen ones would join the workshop and the winning scenarios will be funded to be made a storyboard of and hopefully next year the movie will be produced. We focus on fire and flooding disasters. Jakarta, has around 700-1000 fire disasters occured annually.

We also have a place in Jogja, which we called Bumi Pemuda Rahayu. Here, we invite artists to stay, to work and to make everything they want. Now, five young artists are residing there. There are one photographer, one videographer, one writer and one architect. The fifth one will join on the 17th, he is a maker of bamboo musical instruments.

We hope that it will be an annual program. In fact, if needed, it could be conducted twice a year. There, we could try to deepen an ecological life while creating things. Now, for example they’re experimenting with ecological foods and cookings, like only consuming steamed foods, not fried.

A

How about something you want to personally explore or study in the nearest future?

M

I want to persuade people to make a move systematically: making cities, orientating oneself to ecology. Yesterday I made a paper for the discussion material in Bappenas. To revamp a city into an ecological one needs three things: decoupling, substitution, and recovery. But it needs to be done through many things. From a commununity movement to a shift of rules and a change of system.