Discovering Surabaya with Anitha Silvia

Ken Jenie (K) interviews Anitha Silvia (A), a cultural activist in Surabaya.

by Ken Jenie

K

Firstly, what organizations and projects are you involved in?

A

I am a member as well as volunteer at C2O Library, admin and treasurer for Ayorek!, Indonesian Netlabel Union activist, and admin at Sunday Market.

K

Can you tell us how you became involved in projects such as C2O Library, Ayorek!

A

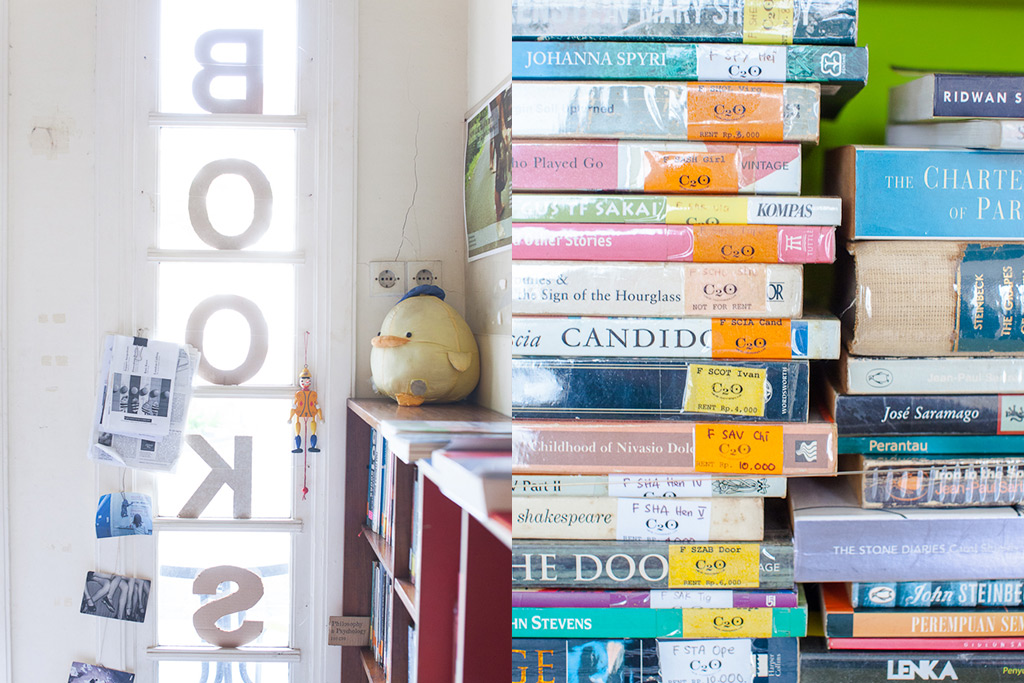

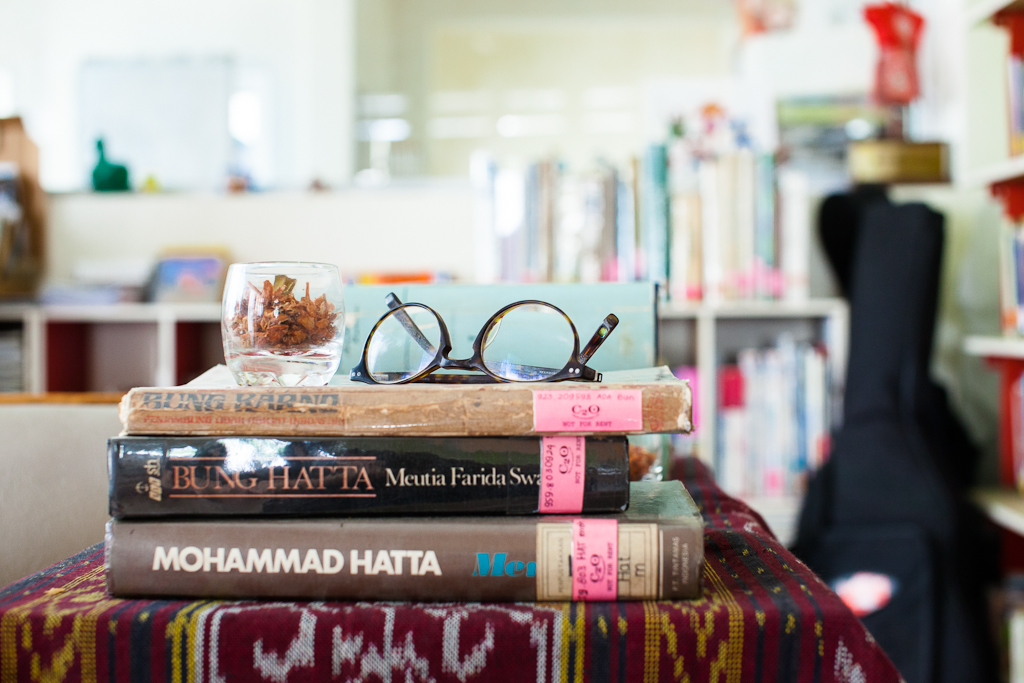

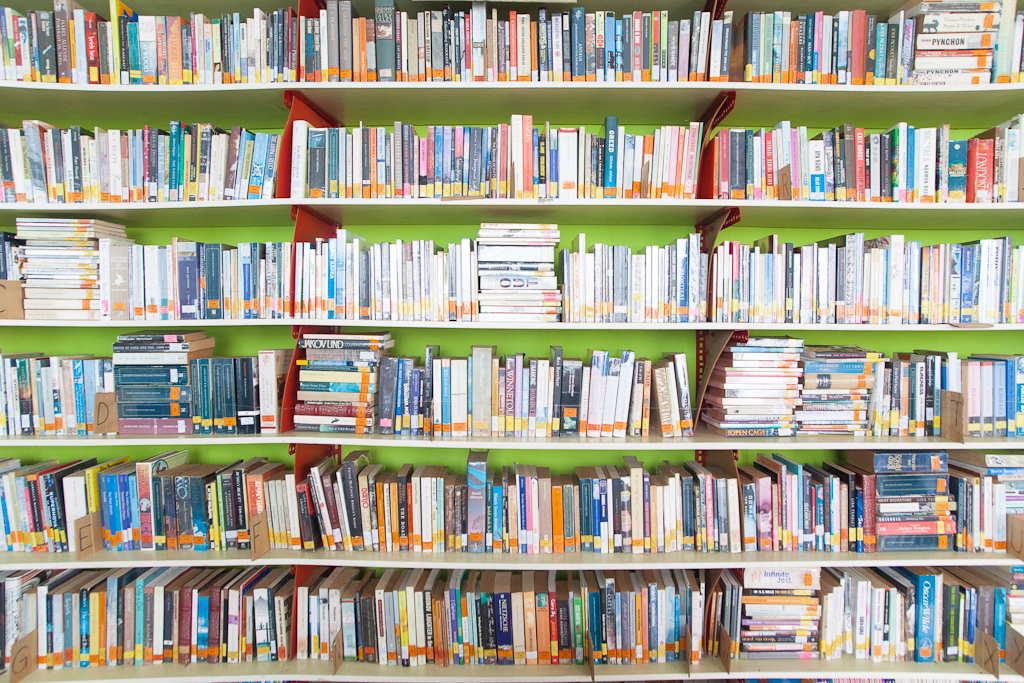

C2O Library & Collabtive is an independent library and collaborative space in Surabaya. I became a member of C2O Library since the institution was founded in 2008. I happen to have met the founder- Kathleen Azali in Kampung Ilmu (Knowledge Village), a used-book market in Surabaya. Kathleen invited me to visit the library, which was close to where I worked at the time. I fell in love with the library. The book and film collection was superb, and the space itself comfortable. Kathleen was very keen on sharing her references of books, films, music, and events – I learned a lot from her. Me and other library members had this yearning to revitalize Surabaya by means of literary activities, so we organized a number of festivals such as Cergamboree (a comic book festival), Books Day Out (a book festival), Eat Play Laugh (a children festival) and Design It Yourself (a design festival).

We try to actualize our ideas (as well as our needs). C2O became the place where we gather, organize, learn, and share ideas as well as realizing those ideas. Since 2012, C2O Library added “Collabtive” to its name, to highlight our activities, which often times is based on collaborative efforts with many other organizations.

In 2011 I decided to resign from a building management company I have worked for 5 years. I decided to become a freelancer, a big decision that I am glad I made because it gave me more time to read books, write, travel, think, and volunteer at C2O Library and Collabtive.

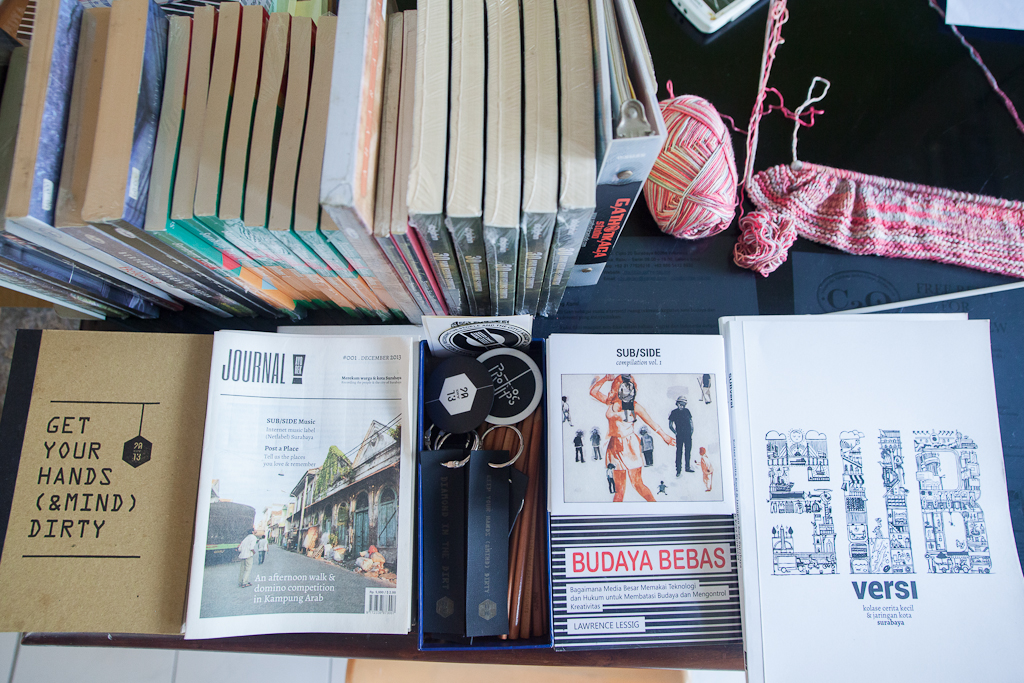

Ayorek! Is a dynamic urban study project supported by RUJAK [Ruang Jakarta] which started in 2012. It is an open platform open to anyone concerned with the city of Surabaya. Based in C2O as well, we intend to connect and facilitate the production of knowledge between a variety of individuals and communities. To be frank, it has been a dream of ours to create a platform using the medium of a website, books, netlabel, and journal for the city of Surabaya. It is a pleasure for us to produce, collect, and distribute knowledge of this city. Right now it consists of Kathleen Azali, Erlin Goentoro, Andriew Budiman, Ayos Puroadji, Adil Albatati, Deasy Esterina, and many supporters.

K

The city of Surabaya is the anchor of many of your projects. From your own perspective, what makes the city of Surabaya so special?

A

I was born and raised in Jakarta before moving to Surabaya for university in 2001. Up until now, I feel that I made the right choice to continue living here. At first I was quite disappointed with the city because it was difficult to find books for references and there was a lack of cultural events – which was a surprise because Surabaya has been referred to as the second largest city in Indonesia. It was then when I realized how bitter the centralization of Jakarta was. Jakarta has made itself the center for everything – the economy, government, and culture.

Because I was “forced” to live in Surabaya, I began recording the uniqueness of the city, the strong use of the local Suroboyoan language. There are still many kampungs in the center of the city, a large population of Maduranese, a strong presence of village culture, Jengki-style architecture, active traditional markets, delicious culinary treats (I am a petis enthusiast), the hot weather, no significant traffic jams. Soekarno was born in Surabaya. The city has a peculiar atmosphere and I fell in love with it.

K

What aspects of Surabaya can you tell us that perhaps most people are not aware of?

A

Surabaya is often described by its nickname, the city of heroes [Kota Pahlawan] – a grand narrative given by the government. This epithet has trapped the city with a theme it uses to celebrate the city (until now). In my opinion, that nickname is no longer relevant to Surabaya. A number of books describe the city as a labor city, a center of Indonesian struggle [referring to Robbie Peters “Surabaya, 1945-2010 : Neighbourhood, State and Economy in Indonesia’s City of Struggle” in which Peters described Surabaya as resisting and adapting to institutionalised economic, social, and political standards], and city of culture – these are topics that are seldom raised. You can check a video we made about Surabaya.

Under the leadership of Mayor Risma, Surabaya has improved in the last couple of years – better infrastructure, more parks, wider and more accommodating sidewalks, 10 Km bicycle lane in the center of the city, and there are plans to build a tram and monorail. A shortcoming is the lack of public participation in guiding Surabaya’s local government and the minimal use of public spaces.

K

Related to the question above, the Manic Street Walkers is a very interesting activity in which groups of people get to know Surabaya by walking to become better acquainted with the city. First question is how did this idea come about?

A

Something that surprised me was that there are hardly anyone walking in Surabaya. Almost all Surabayan own automobiles or motorcycles, their mobility depends on their personal vehicle. Its true that Surabaya’s public transportation is terrible, but its frustrating to see a person using a motorcycle to go to a warung that is only 100 meters away. Most Surabayans avoid traveling by foot by blaming the hot weather, and ill-maintained sidewalks. But by my own experience, I can enjoy and feel safe walking in Surabaya.

I happen to live in the center of the city and to get to my activities in central and east Surabaya I can reach them by foot. A normal person can walk for 1-2 hours every day, but I’m often called crazy because I regularly walk for an hour through Surabaya (laughs). I have discovered many interesting things walking through markets, crossing path with hawkers, being greeted by the locals, finding local architectural details, DIY signage, weaving through small alleyways, meeting a lot of stray cats.

I wanted to share my experiences walking in Surabaya with people, so I immediately suggested to C2O library to make a pedestrian club, which ended up being Manic Street Walkers, a play on words of our favorite band: Manic Street Preachers. We made routes that cater to a theme such as Arab Village, Design Trail, Wandering Through Kali Mas, Jengki Architecture, Peneleh Trip. We have had 20 different routes so far.

K

Would you say that our reliance on automobiles and other transportation has made us less aware of our surroundings?

A

Yes. Like Abidin Kusno wrote in his book, “Ruang Publik, Identitas, dan Memori Kolektif” (Public Space, Identity, and Collective Memory), city inhabitants feel threatened on the streets, they choose to be in their air conditioned cars and modern shopping centers that are super-safe. This results with us being distant and oblivious to the city where we live.

I also use public transportation. Social interaction is important for the livelihood of a city; this is where the community can interact with one another. It isn’t surprising for Surabayan’s to have the person sitting next to you ask your destination and where you live (something that would be suspicious if it were to happen in Jakarta’s public transport).

K

Could you describe what you have experienced doing Manic Street Walkers? What sort of discoveries have you experienced from it?

A

We learned a lot about this Surabaya when we walked through major streets, villages, by a river or train tracks, observing the communities as they adapt to the constantly changing city. For example, when we walked to Gedung Setan.

We often walked by the gloomy building but never dared entering. When we finally decide to explore it, we found that Gedung Setan is inhabited by over 40 Chinese families that were in hiding during the pasca-GESTOK tragedy. There are many more things that we do not know about this city. It is a pleasure to experience it first-hand, and teaches us how to respond to the city.

One walk that made an impression was Jelajah Kali Mas (Exploring Mas River), a body of water separating the North and South of Surabaya. We walked by the river for 6 hours, watching the communities living by the river. Kali Mas has been an important river since the Majapahit kingdom until the colonial era as it was used for transport. Now, Kali Mas is nothing more than a dump for factories and houses.

A lot of our friends who join the tour are astonished just because they were walking in Surabaya, they are too accustomed to using a motorcycle. We would like the citizens of Surabaya to make walking a mode of transportation. I do not want this city to become like Jakarta – congested with automobiles, high levels of pollution, being uneasy on the streets. What we have gathered from our observation is that Surabaya is relatively flat and small in size, making it ideal for citizens to walk and bike.

K

Like C2O and Ayorek! and Sunday Market, you are involved in a number of cultural, art, and community-oriented projects. What would you say is the roles of these events and institutions for Surabaya?

A

We have become one of the city’s pockets of culture, eager to incorporate literacy and the arts into every day life. For the past couple of years neighboring cities (and countries) started showing interest in Surabaya – good bands and films tour Surabaya, well-known publishers such as Komunitas Bambu, Marjin Kiri, and Banana Publishing started distributing their books in Surabaya.

K

What sort of difficulties do you face when executing your projects?

A

Firstly, we are relatively inexperienced as social researchers and event organizers, so there is still a lot to learn.

Secondly, it is difficult to find partners willing to take a risk to create something often considered trivial – this is because most Surabayan still gravitate towards business, making profit. Meanwhile our projects do not prioritize profit, rather building an atmosphere conducive for creativity.

K

You also played a role in organizing Indonesian Net Label Union’s Indonesian Netaudio Festival, the first of its kind in this country. What is the significance of Netlabels in Indonesia’s music sphere? Particularly in relations with Indonesia being such a hotbed for music piracy.

A

Netlabels have become an alternative route to distribute music. The internet is an effective and affordable tool to produce as well as distribute works, so the Netlabel is a platform to share music that is legal and free, a platform that empowers.

Sharing is part of the Indonesian community’s culture, so the netlabel isn’t an alien concept because we have practiced it in our everyday life. To be clear, “sharing music”-here is different from piracy. We generally aren’t well educated in copyright laws – how to wisely produce and distribute knowledge – so our [Net Label Union] goal is to propagate an understanding of fair-use, free-culture. We also work with Creative Commons Indonesia in socializing creative commons licensing. Let us hope that copyright does not hinder the distribution and production of knowledge. Not only limited to music, we also address other fields of interests.

We at Netlabel Union feel it is important to celebrate the freedom of music, hence creating the Indonesian Netaudio Festival. We organize a platform for free-culture through discussions, workshops, and concerts.

Cholil Mahmud once made a statement that I highly respect on efekrumahkaca.net:

“Cholil states that music is part of science, and the advent of the internet has empowered himself with the multitude of information in it, so making ERK’s [Efek Rumah Kaca] work free is a reciprocates all the knowledge the internet and its society has given.”

K

Can one say that Net Labels have become a staple/popular in Indonesia? And why so?

A

Yes, I agree. Yes No Wave Music popularized the netlabel in Indonesia, and became a model for the concept due to its thorough archiving, having its own media (Xeroxed), and gig organizer (Yes No Klub). This model was then followed by StoneAge Records and Hujan! Rekords. Right now there 14 known netlabels in Indonesia that are active.

Indra Ameng boldy stated that music is dead – physical releases are no longer significant, musicians receive appreciation from performing and merchandise. In my opinion, netlabels is a means to address this issue.

K

What is the Net Labels potential?

A

It is a platform that anyone can use if they have a pc, Internet connection, a curiosity for music, and a trusted musical taste. It is a low-cost project with significant results. Netlabels also plays a role as a good music curator.

Netlabels frees music, gives the composer a choice to use the Creative Commons liscence, and it becomes an efficient platform to archive music.

Under Ayorek!, we have created our own netlabel called SUB/SIDE to document and distribute Surabayan music that, for the most part, aren’t archived well by the musicians. They often have not recorded their material in a studio, so we record their performances.

K

What would you say is, or should be, the role of the government in nurturing local art and heritage, and would you say that it has fulfilled that role?

A

Well, the government should be doing their job, but the reality is that we haven’t seen it in Surabaya. The local government in Surabaya via the Department of Tourism choose to highlight traditional arts because it is considered more popular for foreign tourists. The Art Council of Surabaya activities cannot be seen, yet they continue to receive a spending budget.

We have seen positive intentions by the government (Via Bappeko [The City Development Office]) to listen to the youth, who are more productive than The Art Council of Surabaya, but it is still going to be a long and arduous journey to receive the support of the government.

K

If any, what is the current contribution of the government to projects such as the ones you are involved in?

A

Last December Ayorek! was given funding to hold an event in Balai Pemuda as part of a Board of Tourism program. We were ecstatic to finally be given free access to Balai Pemuda and hope to have that access again in the future. Balai Pemuda should be like Taman Ismail Marzuki in Jakarta and Taman Budaya Yogyakarta, but cultural events there are still rare.

K

Do you believe that Indonesia’s creative industry has reached its full potential?

A

Of Course not.

K

Where should it be?

A

“Creative Industry” is a western concept, while in Indonesia ‘creative’ activities have long been a part of all levels of life – from home to the factories. The main issue is improving the education system, after that the creative industry will healthily grow.

K

As you have experience being involved in a variety of grassroots projects, what can you tell us about establishing and creating events in Surabaya (or Indonesia in general)?

A

Humility and persistence to learn from society, sensitive to the needs and character of your community, to be a part of it so the events we make are not alien to them – they become an important component of the event. Consistency is also important, we cannot make an event and then not continue it. What we are studying is how to create an event based on research.

I am very interested in the works of Jatiwangi art Factory (JaF) and KUNCI Cultural Studies Center. I have learned a lot from them – how JaF empowers the citizens, government and soldiers in the Majalengka sub-district, Jatiwangi. How KUNCI researches in city villages and present their findings not only through writings but also other mediums (video, exhibition, music compilation, theater performances, etc).

K

What do you have to prepare?

A

Finding references for a system of operations from other organization, diligently browsing, and visiting other cities to compare, doing simple research to understand the problems you will face.

K

How does one make an organization/event successful?

A

Openness and trust within the team. You do not need a large team, a small and solid team that support each other will suffice, and that happens when you have a common vision and can share references.

You need to be consistent – make a continuous event, collaborate with a number of communities, and be open to criticism.

Document all your activities (catalog, video, photo, audio recordings) and distribute it.

It is not important to move from one cafe to another when working. You need a space to work, gather, as well as store your materials and documentation.

K

Financially speaking, is it a viable venture?

A

Of course, but it isn’t instant. If you have a strong concept and are consistent, there will be parties interested in sponsorships, which can be a source to finance other projects.

K

Anything we haven’t covered in the interview you would like to tell us about?

A

Every city has its own strong points and character. If you are sensitive and have an awareness, you can create a number of interesting things – at the same time making the dream city you want to live in. A blessing in disguise, there aren’t many doing research and creating events in Surabaya, so we have an over-abundant amount of dreams waiting to be realized.

Witness our city through Ayorek!