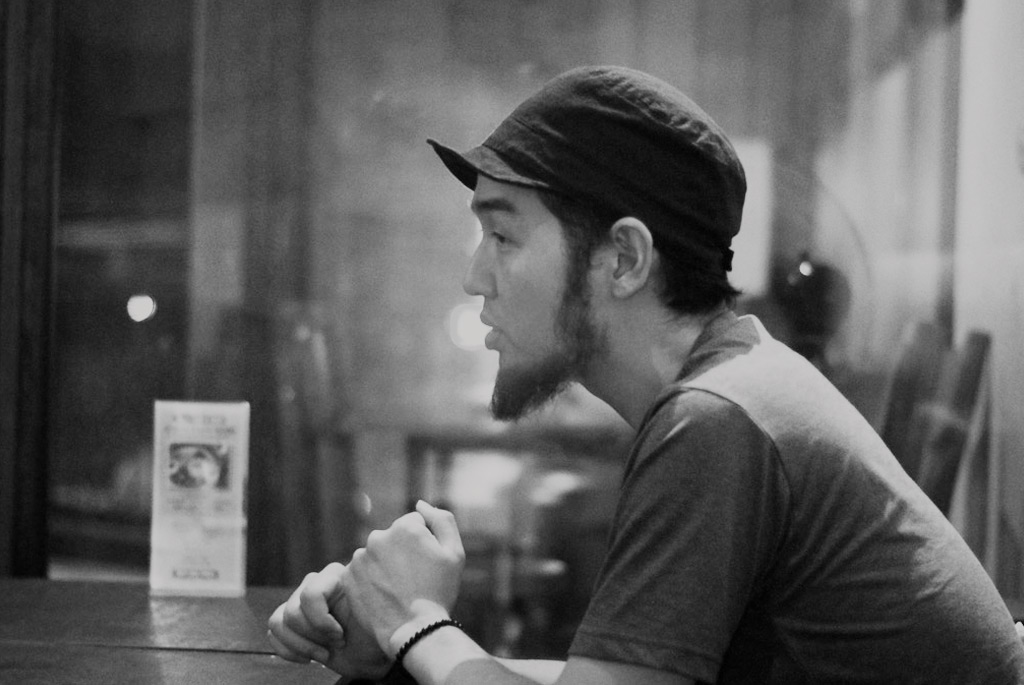

Turntable Experiments with DJ Sniff

Chandra Drews (C) talks to musician Takuro Mizuta Lippit aka DJ Sniff (S).

C

I basically ask this question to everyone I interview – how did get into music in the first place? Just by listening to your art it is a bit impossible for me to pinpoint what your influences are. Was your upbringin musical?

S

There were a lot of influences, mainly because I had older brothers and they always listened to music. I listened to the tapes and the vinyls they had, and then I started buying music. One of the big thing was… I watched this film, Juice.

I always listened to hip hop and rock before, but after watching Juice, I realized that all the things that I was listening to could actually lead to making music. I never took music lessons, I don’t come from a musical family. I always thought that to be a musician, you had to play an instrument and read music. When I saw that film and saw DJs, I realized that what I listened to could lead to making music. I was about 15 then, and I started listening to stuff with a mind that this will all lead to making music.

Practicing an instrument was for me listening to as much music as I can.

C

Where did this all take place? Where did you grow up?

S

I was born in the United States, and my family were always in the states, but I moved to Japan when I was fairly young so I spent most of my youth in Japan.

Japan had all of this information coming in and there was a lot of international music as well as local music.

C

How you first made your own music and how far removed was it from what you are doing now?

S

It actually isn’t that different, actually. I have always felt that DJing was the only way I can make music. What I do has always been having this naysayer telling me what DJs do isn’t making music, they are just playing somebody else’s music. Some people have actually come and told that to me, but it is also something that has always been in the back of my head. I want to make music that has roots in DJing, but is also drastically different – as in creating drastically different music using other people’s music.

I was always into the technical side of things. I wasn’t a battle DJ or a scratch DJ, I was into mixing and like listening to DJs like Jeff Mills, techno DJs who did really fast mixes, and also Cold Cut – guys that brought lots of influences and their set consists of drastically different types of music.

I was trying to make new music with records, that lead to wanting to do something more different, and that’s when I got interested into learning technology. I first tried to create music with tools such as Cubase and Logic, but they were too complicated for me. I started to program my own software, building my own equipment and controllers, which lead me to an idea that I want to capture and sample the sounds while I play the turntable. The music that came out of that was somehow more abstract and experimental.

C

How long was that process?

S

It started about 10 years ago, and I landed in the area that I am in right now 5 or 6 years ago. I always thought that the music that I would make was abstract, but still have a beat. Now my music is mostly experimental, I play in noise festivals, with improvising musicians – places where we can play very loud.

C

The sound that you have today developed for 5 years?

S

I still think that my music comes from the influences that I have been listening to. I’m very much influenced by hip hop, free jazz, improvised music – I use them directly as my sound sources, but I am also trying to capture the innovation that they did. Grandmaster Flash is a huge influence because he knew how to modify his mixer – he had an idea of what he wanted to do, modified his tools, and practiced to make a completely new style. Although right now, his DJ sets are pretty mainstream, not the cutting edge, but what he did initially was really experimental/innovative – it was really unique.

What I am trying to make is something different. The best compliment I received in Yogyakarta was this kid coming up to me and telling me he has never heard anything like it. He didn’t say if he liked it or not (laughs), which is okay, hearing people say they never heard anything like it is great to me.

C

When you left Japan, you returned to the United States?

S

Yes. I moved to the states after college, working for a bit, DJing and organizing events. I then moved to Amsterdam.

C

You’ve been living in Hong Kong for 2 years now. How do you perceive the experimental music scene in Hong Kong and in Asia?

S

Not much is happening in Hong Kong.

C

I’m surprised to hear that.

S

Yeah, it’s not really a good scene. I’m just there for work. But Asia it is definitely more interesting than Europe.

C

In what sense?

S

Europe is a dying culture, it’s been dying for the past 400 years. In Asia, I feel like there is an energy, a freshness, and it is also great that there is no context or history. If I do tours in China, a lot of kids would show up and be energetic about what they are experiencing. In Europe, if I throw and experimental festival the people showing up are people who already know about it, they have already identified with it. In Asia, I feel like I am performing to a new crowd, and I am able to share a new experience with them.

Also, I think scenes are emerging and it is also much harder to be musicians playing this kind of music in Asia, so the ones that are doing it are very passionate about it – they have a tight sense of community.

C

Is there a tight sense of community in pretty much the same across the Asian countries you have visited?

S

It varies, for example, in Korea the experimental music scene is 3 people with an audience of 5. They make great work and get invited abroad. Beijing has a pretty big scene, Taiwan as well. Taiwan would make the same music as the ones in Korea but have 150 people come. Japan is the biggest.

C

How about this part of the world? Is this your first time in Southeast Asia?

S

I have only been to Thailand, and now Indonesia. Indonesia probably has the most in terms of quantity and variety of music. I have only been to Yogyakarta, and I haven’t really checked out the Jakarta scene. In Yogyakarta, I was very impressed with the communal aspect – at my show, I met every generation and every genre of musicians there – and they were all there just hanging out. That seems like a very healthy scene for me – there aren’t much separation and people go to each other’s show.

I think there is a strong sense of community here. I still have to explore the other scenes, but I know that the scenes in Malaysia, Vietnam, and Thailand are smaller than here. I want to go to Laos, Myanmar, and other places too, but there’s probably not much there either.

C

Will you be visiting those countries as part of this Japan Foundation program? Could you tell us abit about it?

S

There is a lot of interest in Japan from Southeast Asia right now, which is politically motivated, but branches out to culture. That is why the Japan Foundation got this money to support artist exchange between South East Asia and Japan. The basic idea is that we travel and do research on music communities in Southeast Asia, and we try to identify the characteristics, challenges they face, and how they sustain it. From there, I try to interconnect the music scenes. I will be curating festivals where we will bring them together, but also try to travel with Southeast Asian artists to other Southeast Asian countries. We will try to build a network and platform for them to communicate with each other.

C

You are also a curator, right? Besides the one you just mentioned, what kind of curation do you do?

S

In Hong Kong I put together shows. I work at a university, and they give me a budget to invite people, so I have been bringing musicians from the US and Europe. I don’t do so much outside of the university right now, I did more while I was in Amsterdam. A lot of people contact me that they are in Asia, so I am connecting them with people from other Asian countries. When musicians come to Hong Kong, I tell them that we can’t pay for their travel and it’ll be a door gig. They won’t be able to cover their costs performing in Hong Kong, but I can connect them to five or six other cities, so they will get an experience and maybe break even in the end. I have been trying to build a circuit in East Asia.

C

How do you view the turntable as a musical instrument?

S

If you think about it, in the last century the major musical instrument inventions are synthesizer, electric guitar, and the turntable.

C

More turntable than sampler?

S

Yes, because the way we use samplers today came from how hip hop djs use them. For me it isn’t hard to look at the turntable as an instrument. It has always been something that you messed around with, you can see it from hip hop and how house djs mix. It is especially important because now we make music using computers, and the hands-on element is gone. We are in such a virtual world, we are missing the tactile sensation, which is important in music. The turntable is the first instrument where you can touch the sound media and playback device – it’s a great feeling to touch a turntable.

The challenge is that every instrument comes with a certain stigma/stereotype. If you are a soprano there is always Kenny G, if you are an electric guitarist there is alway Steve Vai and Eddie Van Halen, right? If you are a dj, there’s always Tiesto – some super-mega dj. What I do isn’t typical dj-ing, the turntable is the only instrument I know how to play.

C

But you also use a bunch of stuff besides the turntable.

S

But that is all based on helping me play the turntable in a different way. I write my own software that allows me to sample the sounds from the turntable and deconstruct the material. My computer sits there with no pre recorded samples, and as I play it cuts out segments of it. They are all connected with the movement of the crossfader – as I move the crossfader it captures sounds and plays it back. So as I play the turntable I am also accumulating new structures – that is how I take the material and drastically change it.

All of the productions I do are based on turntables. Somebody asked me to do an interpretation/composition of their work, I usually have them made on dubplates. My new album is a remix of a whole label, so I basically listened to the whole catalogue, cut out parts, put it on dubplates and replayed them.

I have made a conscious decision, this is my music, the only way I know how to make music is using vinyl.

C

There are so many types of music on records, how does the music on a particular record you play influence the music you perform?

S

That is a good question. DJ Shadow used to do this thing where he would have people bring records and he would mix everything, DJ Krush used to say he can make music from anything he find on the street. For me, it’s kind of both ways. I don’t think I can listen to music anymore without thinking I might use it at some point – the only music I don’t listen to that way are bland, horrible pop music (laughs). I always have the thought of how I can use the music in the back of my head.

I do collect records, especially ones I am influenced by. If I am making noise or improvised music I like to use songs from that genre because it creates a loop. I also collect particular records from particular labels and eras because I like their sound. For example, particular jazz labels in the 1970s had access to really nice equipment, so those things I would just buy. I buy a lot of free-improvised records because they are mostly solos or duos, so it will be easy for me to isolate the instruments. There is definitely a certain ‘tool’ aspect to it.

On the other hand, I also end up using records that are given to me – usually by friends and people I meet at shows. These records are completely out of my ‘search keywords’ so they always add an element of surprise, or something I am missing in my set.

The records that I bring to my performances are about half of things I have consciously looked for, and the other half are random records that people have given to me.

C

Do you deconstruct different music differently?

S

They all kind of come out the same (laughs), but because the material are different, they almost sound like they are different. When I play shows, people will usually think I am making different music, but for me, I know they have the same structures, which is determined by my tools and skills.

The nuances changes. Things come out a bit differently.

C

I noticed that you have used gamelans records in your work.

S

I stopped using Indonesians stuff because people liked it in a weird way (laughs) – in a cliche exotic way. At one point I was collecting a lot of ethno-music records. It was very hard for me to find good-recorded gamelan sounds because they were mostly field recordings so the sounds were not great. I found a couple with really nice, tight sounds, so I was really happy and started using them. I had a couple of videos online with me playing them and people gravitated towards them – that felt a little weird for me (laughs).

Some sounds are very seductive, tempting, and beautiful. I consciously use them sometimes in my set to add drama to it. You know how it feels uncool when you play records that already have pre-mixed stuff on it? Some records would have many scratching or chops on it, and it feels so uncool playing them – I feel the same way when I’m playing records with really nice sounds, and gamelan has sort of entered that area for me. I know people love it, especially in Europe because it is an exotic asian thing and they expect to hear that from me.

C

That sort of excitement toward exoticism is very apparent?

S

Definitely in Europe, yes. I think I benefit from it too, because people have an idea of what Japanese noise, harsh noise, and experimental music sounds like because artists like Keiji Haino, Boredoms, and Otomo Yoshihide have toured a lot – I definitely benefit from that. You’re not really sure if they ‘get’ what you are trying to do, it seems like a preconception. THings I hear a lot is that the music is ‘poetic,’ or that it is ‘zen’ – as soon as I hear the word ‘zen’ my whole system shuts down (laughs).

I don’t blame them for that, but that is why I love playing in Asia – because I know there isn’t much of that preconception and exoticism. Also, growing up in Japan, playing traditional instruments is so uncool. DJ Krush is the only guy that could kind of get through it, but it also gets really cheesy. Cultures have different relationships with their traditional music.

C

Anything coming up for DJ Sniff?

S

I’m trying to tour more in Asia. I’m trying to do projects where I work with material from musicians that I like. I create a remix, and give them back to the musicians as a score, and have them play the remix as themselves. That is something I am trying to work, it feels totally impossible. Usually people hate it when I play their records when I play with them (laugh).

Special thanks to Cafe Mondo for making this Interview possible.