Embracing the Arts with Shunsuke Izumimoto

Whiteboard Journal (W) interviews Cafe Mondo's Shunsuke Izumimoto (S)

by Ken Jenie

W

Hi Shun, where are you from?

S

I am from Nara prefecture.

W

That’s in the Kansai area, right?

S

Yes, I was there from when I was born until I was 18. Then I went to University in Tokyo. I went to school in Musashino Art University where I studied filmmaking. Before entering university, I went to an art prep school where I learned the basics of design. I really enjoyed film and used 8mm film because I like the old school feel.

W

Before you entered university were you already interested and active in the arts?

S

Absolutely. There is a lot of information available in Japan. I love listening to music since junior high school. There is no particular category. I enjoyed everything from punk to hip-hop, and anything really. When I was in junior high school, there was an indie music movement; stuff like Shibuya Kei, and as the music was a fusion of different styles, I became drawn to learn more about the roots of the music.

My older brother was going to high school in America and often sent me cds and videos. Old school hip-hop was really getting traction, stuff like LL Cool J and MC Hammer and stuff. I was more into Miami bass and listened to Too Live Crew and Digital Underground. I was in junior high school so I liked the raunchier and angrier stuff (laughs). I was also into other types of music like Blue Hearts that played rock and roll-powerpop.

When I entered art high school, I made many strange friends that did art like Paramodel. This was when I really got into more underground music. This was when Boredoms released their Pop Tatari album, and there was this TV program in West Japan that only played noise and alternative music. That blew me away.

W

What was the art scene like, particularly the ones that you experienced?

S

That time, it was the beginning of the indie movement. Brands like Hysteric Glamour was on the come up, and when I moved to Tokyo I lived on the west side of Tokyo. West Tokyo was filled with new, strange things. I would regularly see bands like Yura Yura Teikoku and Guitar Wolf before anybody knew them. There was a lot of different communities.

W

When was this?

S

This was about the time I was in university so it was around the early 90s.

W

This alternative art, is it very common to see it in public?

S

I really loved everything: illustrations, comic books. In Japan, there are comic books for adults and children, and alternative ones. I used to collect the alternative comic magazine Garo.

W

That’s a legendary magazine.

S

I collected it since I was in junior high school. Even though I was in a small city, I was able to get those books. But I also like the adult and children comic books.

W

You basically like everything.

S

Yes! I like the major/mainstream culture and I like the underground too. When I was in high school, I was a film freak. There were many video rental places back then so I would save my money and watch films as much as I could.

At some point, I really wanted to go to America because I became a fan of Spike Lee and his films. My goal was to visit Spike Lee’s 40 Acres shop so I worked part time in a restaurant so I can go. My brother was in New York at the time so I went there.

I really wanted to learn more about hip-hop, and to be immersed in its culture but I was too young to enter the clubs.

W

Was your older brother a big influence?

S

Yes, he influenced me. He studied design in Philadelphia. My brother collected American work wear, jeans and what not. I learned a lot about fashion and music from him, but his interest leans more towards mainstream things while I also explored the underground.

W

So what did you do after you finished university?

S

After school, I edited for an broadcast monitoring company for a couple of years and started making independent films. To support my filmmaking, I worked as a freelance graphic designer. I did a bunch of different jobs, working in a factory, restaurant, doing delivery, cleaning buildings – I did it all so I can make films.

W

Any films we can find?

S

Unfortunately I did not bring them with me. I didn’t like regular films, I really like strange films. I was inspired by Mondo Topless and had a male friend go nude and just dance around. I had garage music as the soundtrack. One of the scenes included my girlfriend at the time eating while he was shaking his penis in the background.

My friends and I were once invited to show our work in this really large collective exhibition, the organizers invited upcoming artists, and they didn’t expect our work to be so strange (laughs).

I like works that aren’t too serious on the surface, but have depth. I don’t like art that is too serious because it will intimidate people. When it is light hearted it will attract people to see it and then they can understand the meaning behind the work. Art can be serious without taking itself too seriously.

After a while, I suppose it is because I got older, it became tiring and I never finished my full-length film. During this time my senpai (senior) who worked in Indonesia came to Japan. As we were catching up, he told me that I needed to grow up and take my career seriously. I remember that night very clearly; we were at Blue Note Tokyo.

He then told me that I should go work in Jakarta, that in Indonesia I can achieve my dreams and live comfortably. But, he said, I wont find music and underground culture in Indonesia, that it was all popular culture there.

I was not interested in going to Indonesia at the time, but as my situation demanded me to look for something different, I took up his offer to visit Indonesia. I went to Indonesia and my senpai took me to hotel lounges, places like Blowfish and X-Lounge. He also offered me a job because his office was looking for a graphic designer.

W

What did you think about Indonesia?

S

I was pretty shocked because there is a very big gap between the rich and the poor, and as my situation in Japan got worse and worse, staying in Indonesia became more of consideration. I met my senpai’s boss regarding the job and told her my interest in working in Indonesia, even though I still wasn’t convinced back then.

W

So you returned to Japan?

S

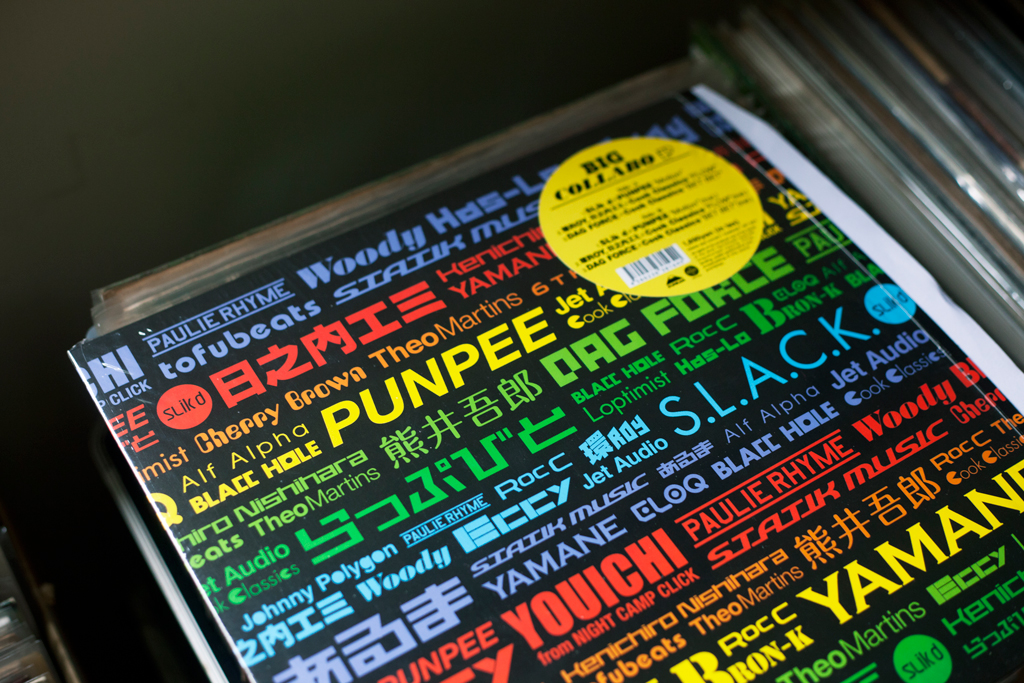

I asked her if she would wait for my decision, she said yes so I returned to Japan. I thought about it, and looking at my situation in Japan getting worse I decided it is time for me to go. I sold everything I had; books, vinyl, everything.

W

Why did you throw away all your things?

S

Because they were memories. I wanted to get rid of the bad memories.

W

It seems like you wanted to start from zero.

S

Yes. I wanted to start from zero. So when I came to Indonesia, all I brought with me was my money. When I got here, ‘making it’ here was harder than it seemed on my first visit. Work was really, really hectic, but I was starting from zero so I felt that it had to be this way to climb the ladder.

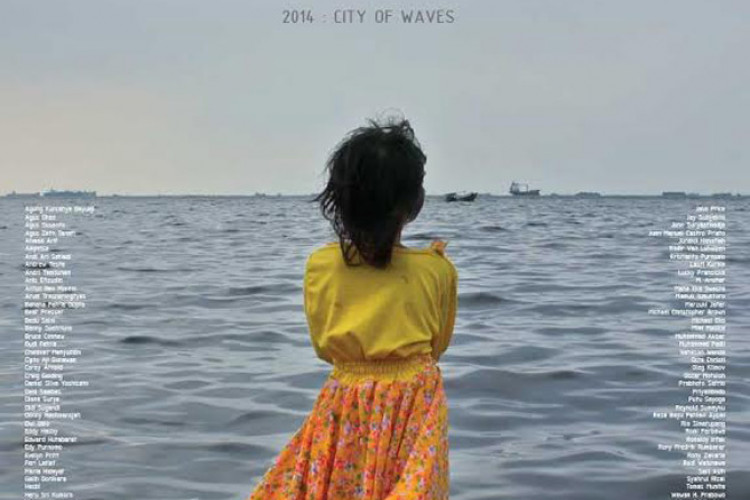

One day I was reading a local magazine, I’m not sure what it was, and found out that Indonesia had this culture.

W

What culture do you mean?

S

Stuff like music, films, fashion, and others. I went to my senpai and showed it to him. I learned about 347 in Bandung, so I wanted to go there. My senpai was interested as well so we went together. When I went there, I found so many different things. They not only had fashion but also CDs and stuff. I wanted to watch a show there, and I went by myself to this show. There was everything from street punks, grindcore, to hardcore.

I was really excited so when I returned to Jakarta. I constantly surfed the internet to learn more about the local scene, and every weekend I would go to shows. When the German death metal band Sodom performed in Jakarta, I met Anggi from Speedkill and we hit it off. He really was my first Indonesian friend, and he took me to different places, from tattoo places to independent shops.

As for Jalan Surabaya, I believe I first went there because I had to accompany a Japanese guest sightseeing. The guest wanted to see antiques, so I found Jalan Surabaya. I was really surprised when I found that they had a lot of vinyl there. That’s also where I learned about Indonesian music such as dangdut. The music culture intrigued me, and I started visiting Jalan Surabaya regularly. That is where I met Aat, David Tarigan, and more – at Lian’s shop, it’s like a salon (laughs).

W

And all of this time you were still working as a graphic designer?

S

Yes. I wore formal clothes, my hair was cut short and everything (laughs). It was a good job, but I wanted to try something new. I talked to my boss and she wished me the best of luck, and about 2011 I left after the company found my replacement.

After looking over my options, I decided to do my own thing. I asked Tomoko to help me make a Cafe.

W

You worked with Tomoko beforehand?

S

Tomoko worked in management at En Japanese Dining in Senayan. During that same time she was planning to go back to Japan to open a cafe there. I met with her and told her that I wanted to open a cafe in Jakarta. If she was interested we would go ahead and do it, but if she didn’t I was going to go back to school. We went ahead and looked for sponsors to create this place.

I also then asked Aat for help. I also wanted to open a record shop, and I asked him if he wanted to open one. He is very knowledgeable about records, and in his heart, he is a very DIY person because he is a punk. He is a punk that doesn’t limit himself to punk. He listens to and appreciates everything.

I asked him for help and he agreed.

W

How did you come up with the idea of a cafe in the first place?

S

As the economy goes up like in Indonesia, people start to focus on luxury, and then people begin to appreciate its own culture. I know a lot of Indonesian music, and when I talk to the average Indonesian person about music such as dangdut they laugh at me – I don’t understand, why don’t these Indonesian kids appreciate their own culture? There are a lot of people in the non-mainstream that are aware and enjoy local music, but the mainstream must have that awareness as well.

The cafe can be a place where I can introduce this music in a context that they can be at least be aware that Indonesian is good. Also, if I have a cafe I can invite local and foreign acts to perform. I want to make many different events, not just be limited to one category – indie for example. I want a place that can accommodate everything from house, hip-hop, reggae, to Indonesian. People discover new things in this place, like a couple of events in Mondo a couple of crust kids came to a noise show and said that it was good and they can relate to it – I want to cross cultures.

W

So your goal in Mondo is to educate about music?

S

Not education, it’s more about sharing. Education has a chief entity that dictates information. I want people to come and share their information with me, and I can share information with them as well.

Why the name Mondo? Well the word ‘mondo’ means world in Italian. But in America, the word is known to mean ‘strange films’ because around the 60s or 70s, there was a film called ‘Mondo Cane’ (a Dog’s World), a shock documentary. The Americans watched it thinking it was strange, and soon the word Mondo became a word that means strange films.

In Japan, they interpreted the word Mondo from the Americans and think it actually means strange. It’s a very interesting story of a word, so I chose Mondo for the name of the cafe.

W

A pretty basic question, in your personal opinion, is there such thing as good and bad music?

S

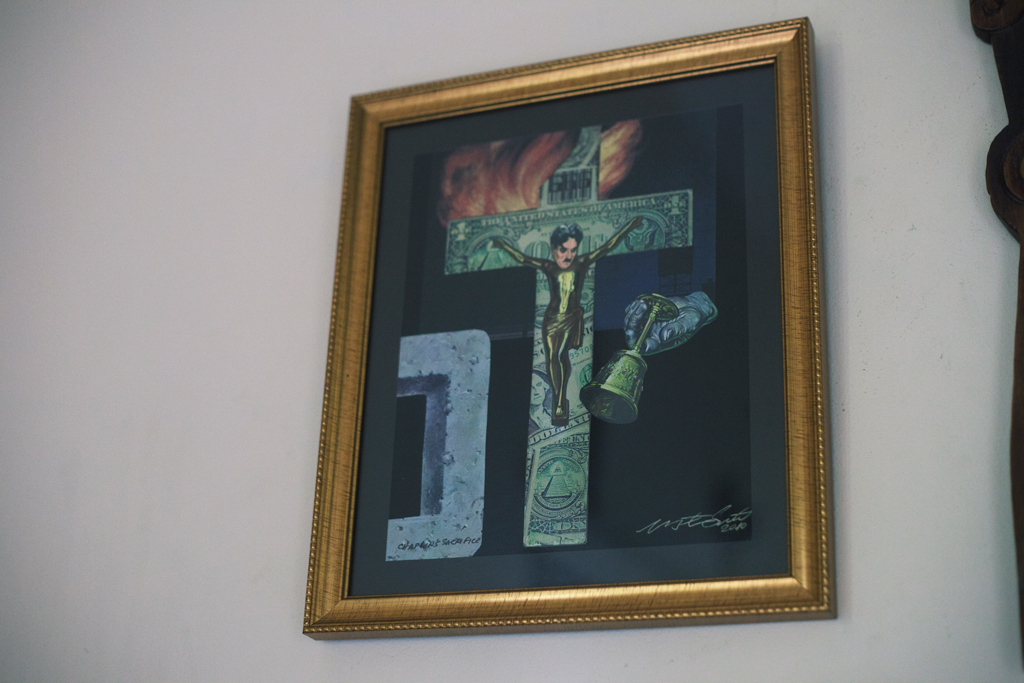

In reality there isn’t. The system is the problem. The artists have no fault in this.

W

What do you mean the system?

S

A lot of it has to do with the marketing. For example, the girl group AKB48 created a contest where you have to buy their CDs to win a chance to shake the girls’ hands. It’s like those chocolate bars that offer a free sticker; children only want the sticker. What is important is the chocolate, not the sticker. That was the case for AKB48, what is important is the music, but people are purchasing their album to win a contest. That is a waste. All of it is for the money, and it shouldn’t be that way.

Oh, one thing, I cannot enjoy racist music. I hate it. Don’t use music for ideologies of hate.

W

What is your opinion on the Indonesian scene?

S

Excellent. Major or underground, it is excellent. It is just the system that I don’t like. The industry needs to stop trying to imitate foreign music scenes. They should nurture the music scene here and develop its own character.

W

Right now there are a whole lot of groups that emulate the K-Pop phenomenon…

S

That’s fine. I’m not particularly a fan of the music, but it is an interesting phenomenon. We may say that the quality is bad and so on right now, but who knows what it will give birth to in the future. In retrospect, it could be a really good thing.

It really is the system. In general, the problem that I see in Indonesia is the system. It needs to set its priorities straight. If the system is fixed, Indonesia will be a lot better. I’m sorry, guys.

W

It’s okay, we think the same thing (laughs). What do you see we need to do to improve things?

S

I think we need to be more united. There are many communities, and they need to come together. Aat and I had the idea that we should make a festival and invite everybody in the underground culture to contribute and have be open for public.

W

What’s so special about this place?

S

Even though the gap between the rich and the poor is wide. And even though it seems like a limitation, the underground culture never limits itself. Jakarta is a chaotic city, and I really like it because everything is born from chaos. Perhaps because I am a Zen Buddhist and believe that things are born from chaos. Don’t believe anything at face value. Just because it seems a certain way, it doesn’t mean that it is so. We were taught from a young age that red is red and green is green. What we have to understand is ‘what is red and what is green?’