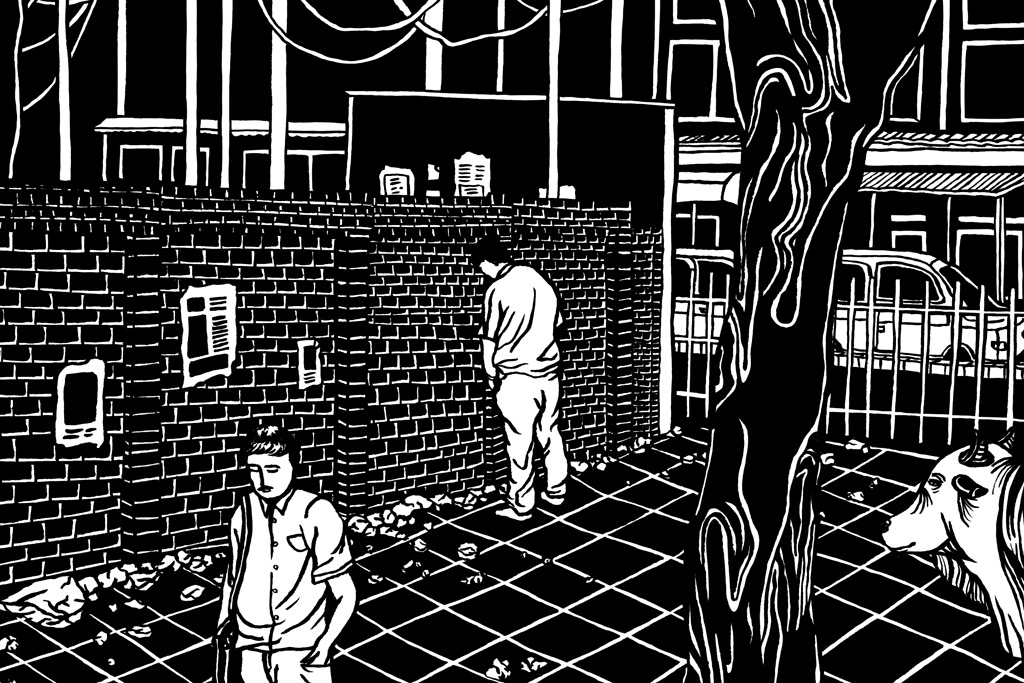

The illusion of a global community whose members are able to connect on a profound level regardless of their cultural backgrounds is one of the products of widespread Internet access. The Internet has turned information that was once exclusively local, inclusively international. One may think that this openness would make us less ignorant about the world, but more often than not the screens of our computers or smartphones only show us very specific details within a limited context. As much as we hate to admit it, we are still not immune to culture shock no matter how well informed our tech-savvy generation claims to be.

What makes culture shock “shocking” is that it is rarely caused by spectacular gaps between two or more cultures. We are so used to our daily habits that we forget – even if we know, in theory – that people in other places have their own collective habits. Differences as harmless as standing on the right side of an escalator instead of the left (or standing on whatever side one pleases, as is the case in Jakarta) or eating with chopsticks instead of a spoon are enough to cause a sense of disorientation. I would love to continue listing all the differences I have in mind, but there is one issue that always forces me to adjust and readjust my standards: hygiene.

As a topic, hygiene is a bit too broad, so to put things into perspective, let’s think of hygiene in terms of food/table manners and toilets. When we are on vacation, we are usually too busy stuffing ourselves with local specialties that we rarely take the time to think about the dining etiquette of the culture in question – much less about the condition (i.e. facilities and cleanliness) of the toilet we might have to visit right after a meal. These matters may seem secondary to our exciting itineraries, but it is always useful to do some research in advance to minimize the many possible effects of culture shock; such as embarrassment, confusion, or even the reluctance to travel ever again. The shock could also result in admiration, but in my opinion, being too enamoured by the foreignness (or exoticness) of any given culture is just as dangerous as hating it. Both scenarios would not take us beyond first impressions.

My most memorable experience of culture shock was when I first travelled to Japan. First of all, the country is so aggressively clean (no litter in sight and hand sanitizers everywhere!). Then there’s the bowing, the festive greetings at restaurants and stores, and of course, Purikura (Japanese-style photo booths with bizarre editing options). Out of all the strange and fascinating things that Japan had to offer, two things stood out for me: food – the food itself and the way the Japanese treat their food – and toilets. I was truly amazed by the great care with which food was prepared, presented and consumed made. The toilets equipped with buttons for numerous functions – including one that played music to camouflage unflattering splashing sounds – still amuse me.

And I wasn’t the only one who found those two things interesting. Roland Barthes, the author of Camera Lucida and many great books, made several interesting comments on the use of chopsticks and Japanese cuisine in Empire of Signs. Though some of his comparisons between Western and Eastern cultures were sloppy to say the least, his observations on the various roles of chopsticks would be helpful for anyone trying to learn about Japanese cuisine. In the brief chapter simply entitled “Chopsticks,” he noted that the tools’ four functions are to point to the food, to pinch the food, to divide, and lastly, to transfer the food from the dish to the mouth. He suggested that chopsticks were not designed to inflict harm on food – a trait not possessed by knives.

Though casual travellers looking for a relaxing getaway might not be interested in Barthes’s cultural scrutiny, it would not hurt to imitate his method of focusing on little details. Museums, monuments and art galleries can offer all the historical facts a visitor needs to know about a city or a country, but I believe that the forgotten and seemingly insignificant details of day-to-day life show us what a culture retains and replaces.

“Compared to Westerners, who regard the toilet as utterly unclean and avoid even the mention of it in polite conversation, we are far more sensible and in better taste,” wrote Junichiro Tanizaki in his extensive essay on Japanese aesthetics, In Praise of Shadows. Several sentences later, he went on to state, “Anyone with a taste for traditional architecture must agree that the Japanese toilet is perfection.” This rather exaggerated fascination for the toilet is not a universal sentiment, but it is precisely the non-universality of it that sheds light on the various priorities of various cultures. Like Barthes, Tanizaki also made stereotypical comparisons between Western and Eastern cultures, but his rather lengthy explanation on the importance of toilets is consistent with the reality of Japanese culture until this very day. Those who have set foot on Japanese soil – even for a brief layover at the airport – must have experienced the odd luxury of Japanese toilets. As travellers, we have a choice: do we want to see the high-tech toilets as they are, or do we want to make connections to the wider culture?

Once we take something normal – be it a pair of chopsticks or a toilet – and place it in a cultural context, its layers will show. Will you peel off the layers, or will you simply acknowledge them and carry on with your itinerary?