On January 19, the second edition of Light to Night Festival Singapore opened. The title, Colour Sensations, is no misnomer: The National Gallery is coated in colorful digital projections throughout the night while putting a roof over equally colorful interactive digital works by the immensely popular Japanese collective teamLab. Surrounding the Gallery is the normally vacant Civic District; now filled with walk-In installations, “multi-sensorial kaleidoscope” (sic), and marquees of popular street food and live music to welcome Singapore Art Week 2018. Festival goers are fed with endless mesmerizing artworks—or in this case, backdrops—that might as well scream “I look good on your Instagram profile”. As evident in the over 2,500 instagram posts adorning the tag #LightToNightSG, these works are the crowds’ favourite. If you’re in for finding a needle in a haystack, however, you might just discover powerful participatory works by Southeast Asian gems Pinaree Sanpitak, Ho Tzu Nyen, and David Medalla. Defeated by in-fashion aesthetics, their presence is deafened by their more Instagram-worthy counterparts.

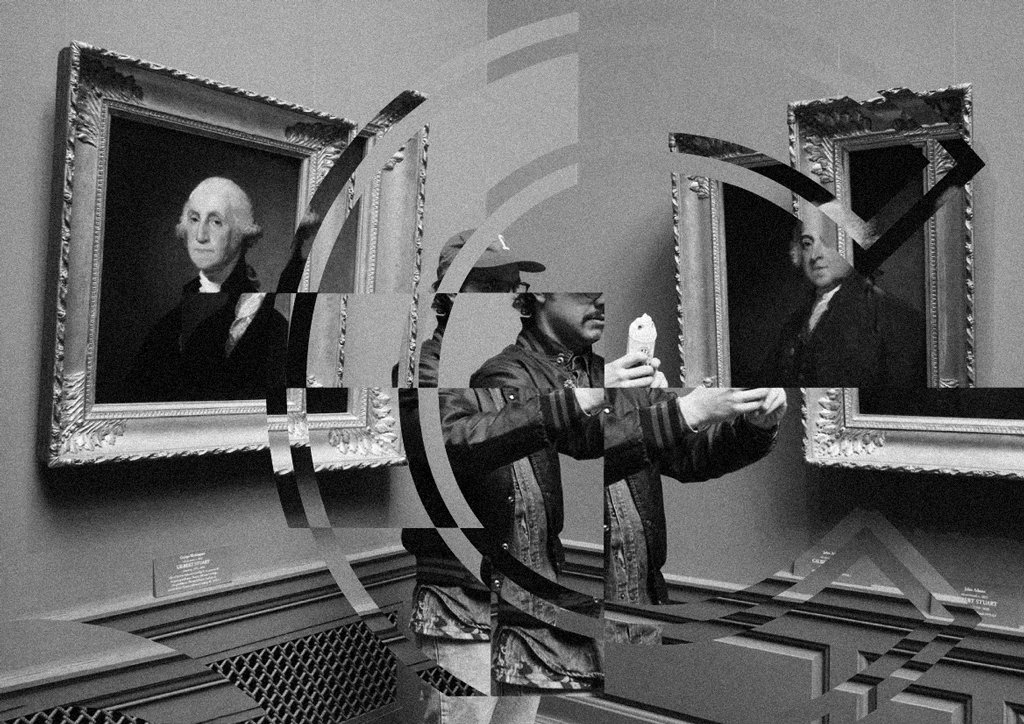

Any millennial could tell you that this phenomenon isn’t new. A good few years had passed since the most conservative museums discarded their no photography policies; institutionalizing and normalizing the practice. Soon, it began to direct curatorial narratives. Such was the case with Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Wonder, which featured nine awe-inspiring site-specific installations. The show saw more visitors in six weeks than the Renwick itself did in the previous year. In Southeast Asia, the National Gallery Singapore received record-breaking crowds from across the region for their show Yayoi Kusama: Life is the Heart of a Rainbow in 2017. The Gallery had to extend their opening hours to welcome visitors who jump from one instagram-worthy artwork to another, and the hashtag that they injected into the show’s social media hype, #sgloveskusama, now holds over 13,000 posts, and if you could find any that does not involve mirrors or the obliteration room, you might as well be scouring the wrong tag. Of course, there isn’t anything wrong with beautiful, out of this world artworks; and there isn’t any question whether the artists or their works are worthy of such attention. But the overwhelming exposure and traffic these works generate for museums and galleries pin them on an uncharted territory between being genuine staples and crowd-pleasing spectacles. It seems that the moment smartphones and social media altered—or, more appropriately, defined—the way we interact with art, any evocative messages they hope to convey are lost inside the obsession their aesthetics provoke.

There is no arguing that this phenomenon has brought an industry accused of being exclusive and elitist into the open air. Emerging from this phenomenon is nearly effortless publicity as well as audience engagement, and something art institutions have long fought for: a wider audience. The rise of this phenomenon has given institutions a sense of self-reproach, a growing agitation around excessive linguistic and academic barriers superimposed on exhibitions that have long barricaded the lay audience from understanding—much less appreciating—art. Perhaps this facile accessibility is the ultimate victory for both art institutions and the public: as creations whose basis of appeal lies in their external aesthetics pave their way into museums and cultural institutions, high art is recast and redefined. After all, what is institutionalized popular culture if not culture itself? The belief that these institutions are dumbing down or selling out by including such works is now nothing but the thoughts of an art snob. Under this view, institutions and their exhibitions automatically lose their drawing power when they abstain from popular culture.

However, this might not be the case. Turning heads in Jakarta since November last year is the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Nusantara (Museum MACAN), which up until recently has been perpetually flooded with an overwhelming crowd that turns the Museum into a photo session “fitting room” as they embark on a quest to find the most beautiful backdrop. However, their inaugural exhibition, Art Turns. World Turns., is nothing like the Renwick’s Wonder: most artworks displayed are of traditional media, with the exception of Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Mirrored Room — Brilliance of the Souls. Even so, the tag #MuseumMacan now shows countless carefully staged photos in the middle of the Museum’s mini corridors and wall texts (the pose “pensively looking away” is the convention), which begs the question: does it still matter what kind of art an institution chooses to display? Or has this phenomenon become so embedded in our subconscious that art and its institutions are only valued as ornaments to our vanity?

This phenomenon drowns not only the comfort of museum-goers who come to contemplate, but also art institutions’ motivation and ability to stimulate something more than awe, which now seem more like a naïve ambition than a viable mission in a world dominated by curated square tiles. This new breadth of accessibility may be feeding a phenomenon that is increasingly used as a control variable in creating the museum experience, but it might not guarantee participation nor lasting interest. As this paradox unfold, institutions might find themselves forced, time and again, to succumb to this culture of “snap and split”; a fleeting, artificial interest that ends with the perfect shot and the cathartic Instagram upload. Soon, they might find themselves treading a delicate path between accommodating the general public and under stimulating the art savvy.

This phenomenon, perhaps, is as good as a revolution. Though the victor might only prevail in the eye of the beholder, the battle is universal. Granted, this discussion still holds layers that have yet to be explored; but one thing is clear: awaiting beyond this victory—this paradox—is a new breadth of institutional responsibility. Popular demand and perceived artistic integrity will push and pull until it reaches a new normal; a status quo that will continue to shift, one Instagram post at a time.

“Friend or Foe” ditulis oleh:

Amaryllis Puspabening

A fervent art student and enthusiast. She writes sentimental poems as well as earnest essays on arts and culture and women’s rights. She was previously a contributor at the Huffington Post.