Critics of consumerism repeatedly emphasize the dangers of our ever-increasing attachment to material things. We are becoming more and more enslaved by our possessions. There always seems to be something new that attracts our attention, and the more we look at it – whatever the object in question may be – the more curious we become, and out of that curiosity emerges a burning desire to own. We feel compelled to purchase things that are interesting to us, but if we were to only feed our sense of curiosity by endless consumption, wouldn’t we run out of money? And even if money weren’t an issue, wouldn’t we eventually run out of space to store our things?

While there are indeed many concerns regarding our consumer tendencies, and even more about how those tendencies only seem to be perpetuated by the current model of a more or less borderless market, it is also important to remember that objects have a crucial role in helping us learn about the past. Without tangible things, we would not be able to complete the jigsaw puzzle of human history. In this case, the amount of money we spend on objects becomes irrelevant. What counts is the value – particularly historical value – that each object holds. Objects are the products of people, and since people are influenced by the place and time they live in, as well as the cultural values they have been accustomed to, the objects that are produced will always have different characteristics.

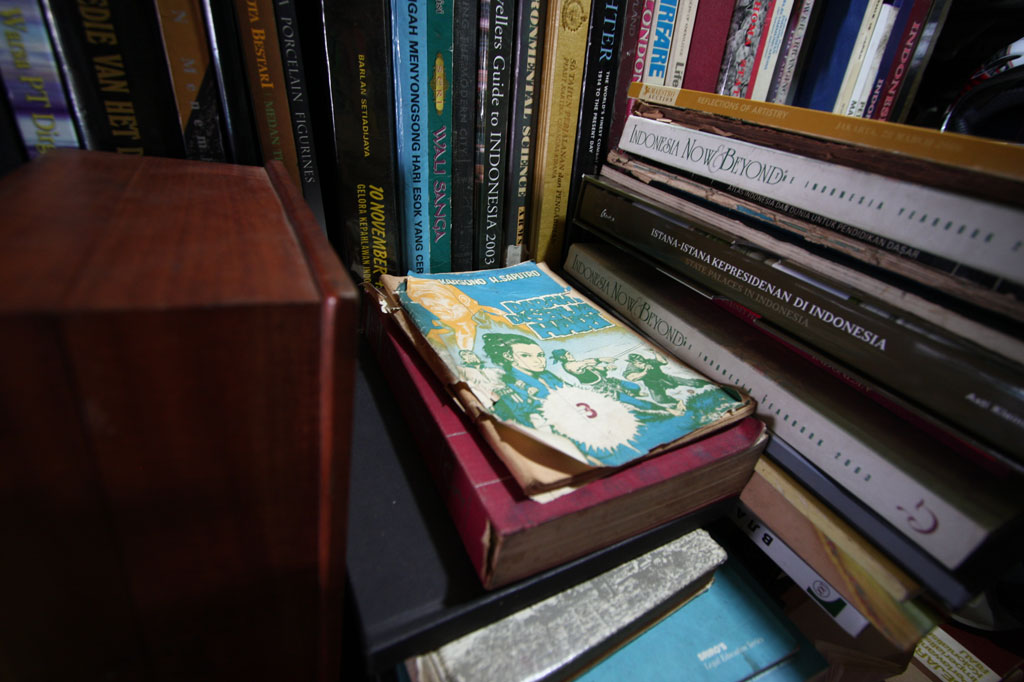

An object that is appreciated for its historical value is usually judged in terms of time; the older the object, the more valid it becomes. But antiques are not simply old things, as H. Abdul Gani, one of the first merchants at Jalan Surabaya Market in Jakarta, stated. For an item to fall into the category of “antiques,” we need to learn about its background; such as the object’s place and era of origin or the way it was made. How can we claim to own an “antique” item if we only know its age? How can we appreciate its historical value? After all, isn’t it much more interesting to have beautiful vase with a story attached to it than one that is just nice to look at?

One might think that being nostalgic for a time that we have never experienced is ridiculous, and that antique markets only encourage an unnecessary wave of sentimentality for anachronisms. But as the Danish philosopher Soren Kierkegaard wrote, “we live forward, but we understand backwards.” A quick interpretation of this would be that he believes humans do not make sense of life immediately, and that in order to put two and two together, a considerable number of days, weeks, or even years, need to pass. Tangible things – whether it is a book, an intricately decorated spoon, or a record that has not been re-issued – connect today with yesterday, tomorrow with today.

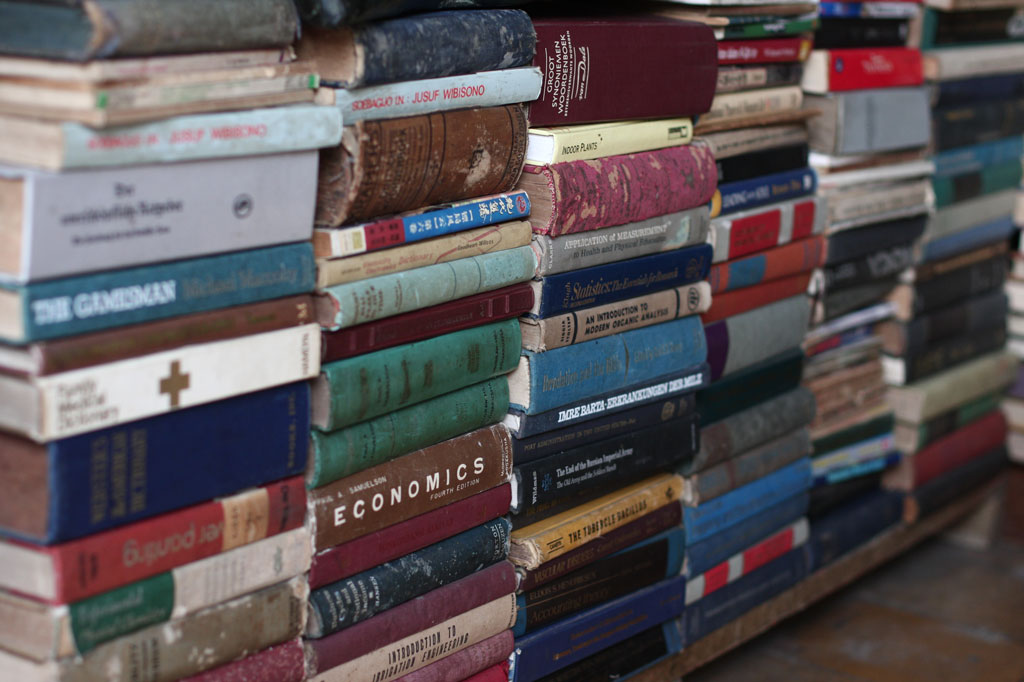

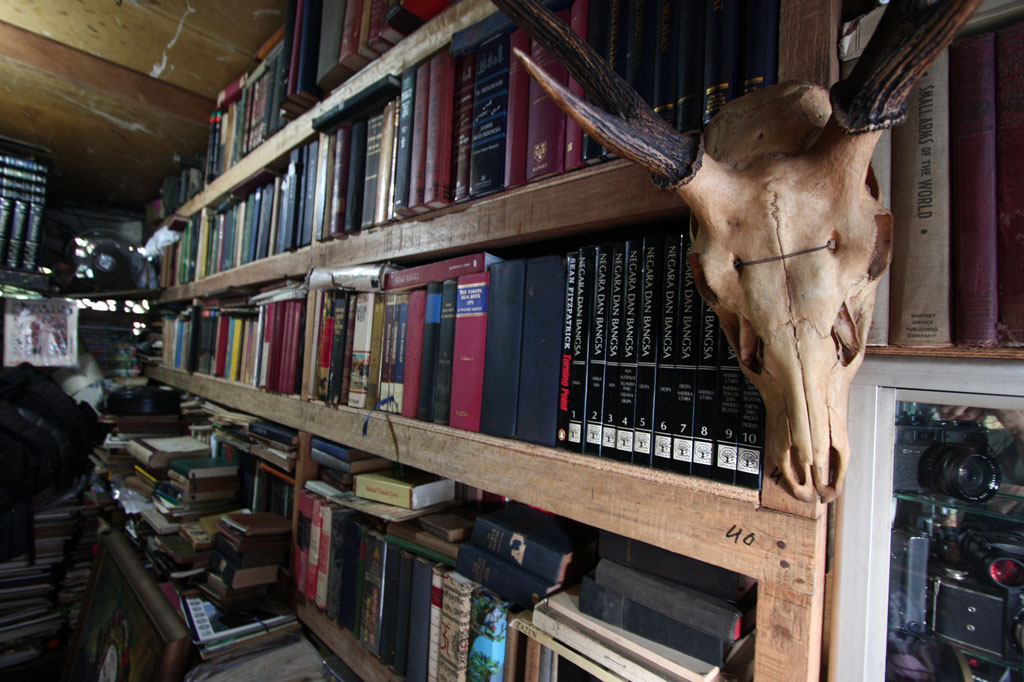

H. Abdul Gani is a bookseller with a mission. Since Jalan Surabaya Market’s formal establishment in 1974, he has been selling books for the sake of preserving Indonesia’s history and culture. Though a number of his most loyal customers are part of the country’s older population, his store has attracted college students as well. He takes this as a good sign, and wants to encourage the current generation to write about the things that are related to the cultural or political state of Indonesia. In his opinion, it is our responsibility to keep the story of Indonesia alive.

But what is interesting about Mr. Gani is that even though his carefully selected collection of books are almost exclusively about Indonesia, he is not the slightest bit picky when it comes to language. To him, the essence of books is the content. That is not to say that languages are not an important factor – no, far from it. As a person who has seen the countless fluctuations of Indonesian society, he thinks that language ought to be flexible. The key is the will to document and pass on the Indonesian experience, not necessarily the language itself. Even the books in his store are available in different languages – from Dutch, German, English to Indonesian.

Old and rare books, however, are not the most common “pieces of the past” that the market has to offer. Most of the stalls along Jalan Surabaya sell antiques such as chandeliers, assorted silverware, and typewriters. Two antiques dealers, Engkos and H. Roni, have been hunting for items in Java and Kalimantan since they started their career in 1972. Engkos noted that the most plausible reason behind the sustainability of the antiques business is that there will always be people who want to have rare things, things that others do not have. And it is often the case that such people are very specific and extremely knowledgeable about what they are looking for.

Both Engkos and H. Roni have regular customers who have been requesting items for many years. But recently, they noticed that the people who drop by their stores are getting younger and younger. When asked about what they think about this trend, they said that kids these days probably just want to have a taste of eras that they were not a part of. In other words, the imaginary sense of nostalgia is a product of curiosity, if not a collective refusal to be excluded from the past.

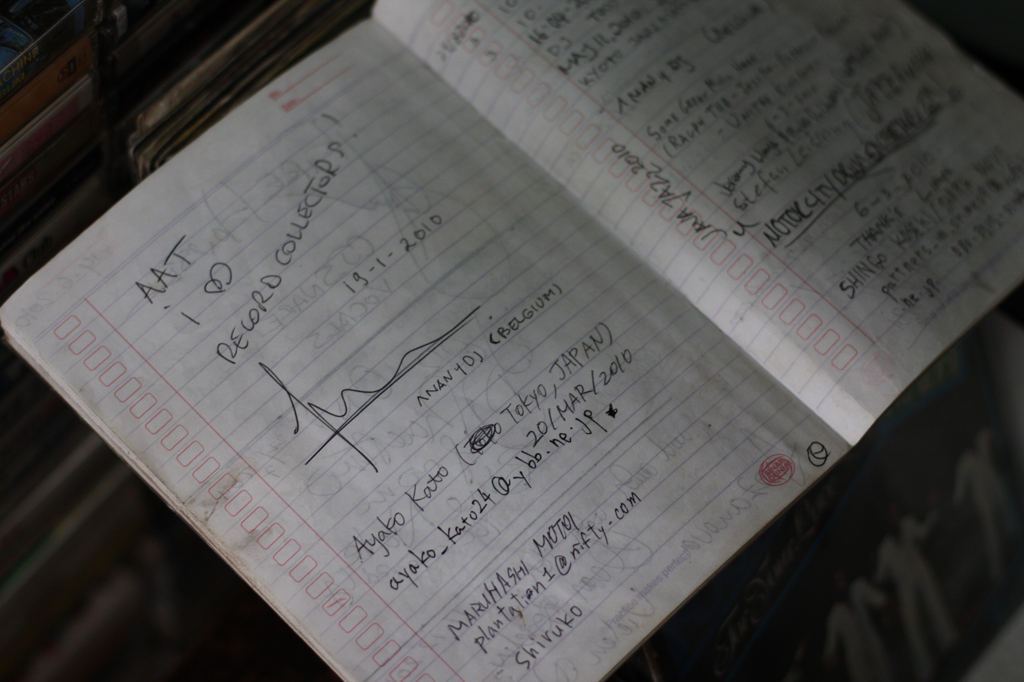

And yet the reason behind the younger generation’s growing fascination with antiques is not always emotional, but also functional. Lian, the owner of a small but famous record store, said that a lot of Indonesian youngsters are starting to turn to records – particularly old Indonesian pop music that have no longer been re-issued – because many are being taken out of the country. Many of Lian’s customers are collectors from other countries, so whatever is left of those rare Indonesian records must be shared among local and international music enthusiasts. Scarcity has triggered competition.

Originality is important when it comes to records, especially to those who are obsessed with the medium. Copies are not good because the quality of the sound will change, said Lian. While he admits that original records are difficult to find – and not to mention, expensive – he thinks that this scarcity will push currently active musicians to return to records, or at least, to prevent them from disappearing completely. Compared to more modern formats used to distribute music, records last longer, so there is no reason for real music lovers to not want to keep having them around.

Will the things of today – laptops, iPads, and minimalistic pieces of furniture – be the antiques of tomorrow? I guess nobody knows for sure. But we ought to worry less about the possibility that products of the past will cease to exist, and concentrate more on creating things that will be worth searching for in the future. The fact that Jalan Surabaya Market still lures in visitors means that the past is a timeless source of interest. “Antiques” will always manage to find their place among society – especially among those who are aware of their value. H. Abdul Gani, Engkos, H. Roni, and Lian are among the many witnesses of the survival of antiques. They are confident that “old things” can coexist with new things. In the end, the words “old” and “new” are relative. What is considered new today will be old tomorrow. As long as the clock keeps ticking, we will never run out of “old things.” It is all a matter of time.

Jalan Surabaya Antiques Market

Jl. Surabaya

Menteng, Central Jakarta