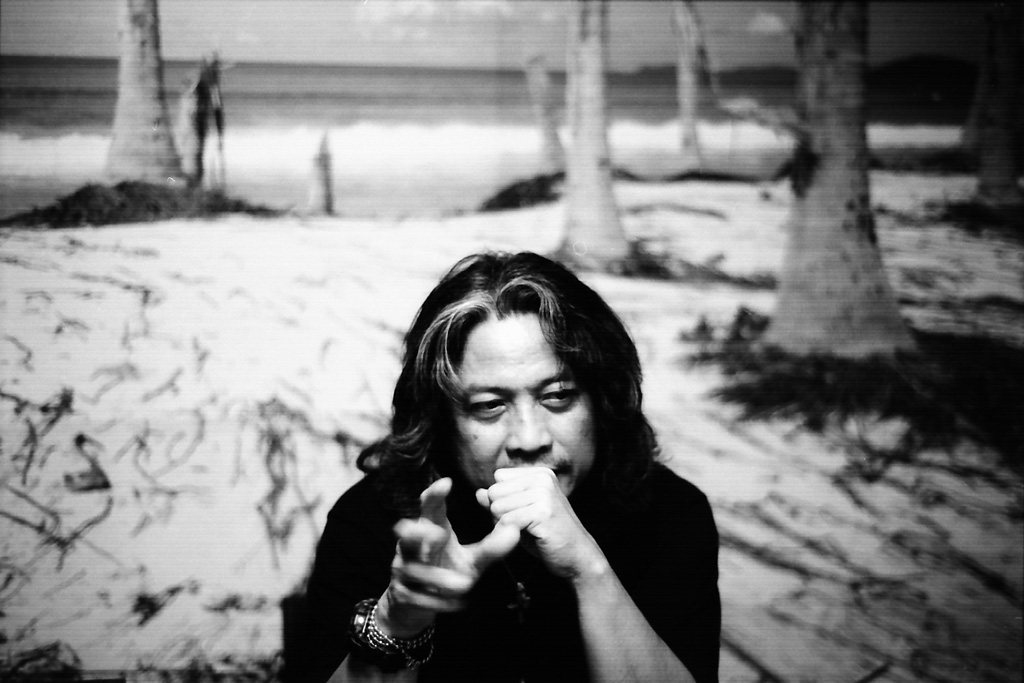

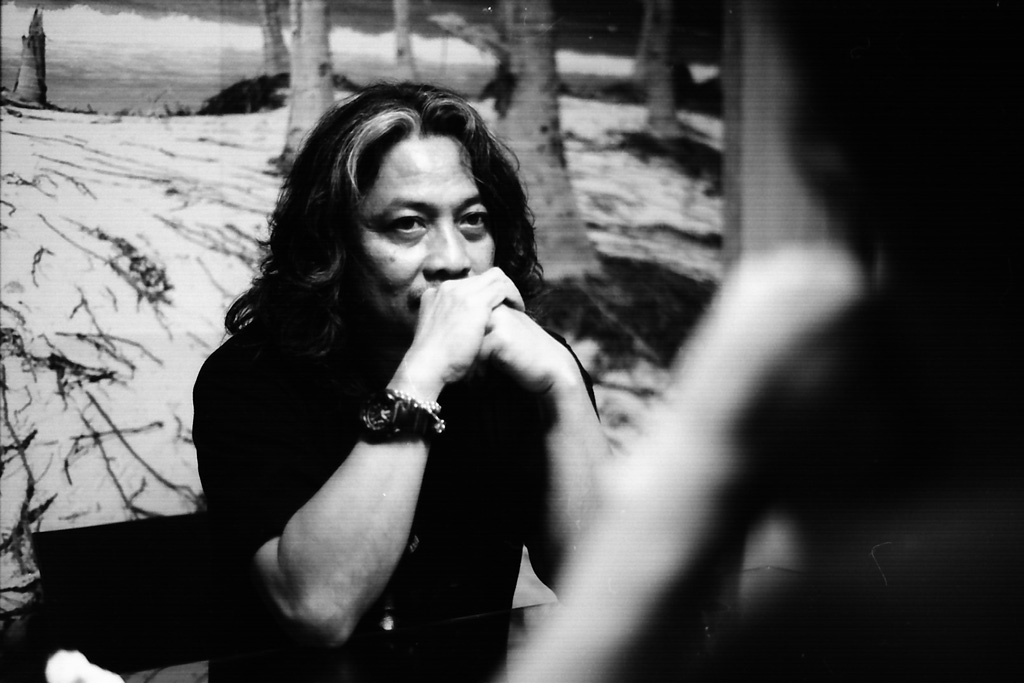

Indonesia and Photojournalism with Oscar Motuloh

Athina Ibrahim (A) Interviews Galeri Foto Jurnalistik Antara's Oscar Motuloh (O)

by Ken Jenie

A

We read that you taught yourself photography, how did you get into photography and what initially drew your interest?

O

I taught myself because of my profession as a reporter. I became a reporter after I graduated from college, where I took a course in Antara News Agency, so my initial thought then when I finished that I would be a reporter. I joined in the year 1988, it was only after two years as a reporter that in 1990 I moved to the photography division – where I had no background in – but I had the basic journalistic skills, so that is when I learned photography.

A

Were you were always interested in Journalism?

O

I never had an interested in Journalism, my only thought was I needed to work after I graduated and I took the chance to work anywhere. So I worked in Antara News Agency, where I took a course for a year and first became a sports reporter, then I started reporting different subjects. That is where I got my journalistic experience. My bosses had a plan to have people of my batch to continue photojournalism because a few of my seniors were retiring and the generation after it were not adapt for photojournalism.

So they appointed me, I wasn’t so pleased at first because I had no prior experience nor background in photography, but I still thought of it as an interesting offer, so with my background in writing/reporting, I was taught photography by my seniors and meeting fellow photojournalist on the field, asking technical tips on how to properly use the equipment. Eventually I found it interesting and thought about reporting from a visual perspective.

A

Seeing your photography work now, I noticed that many elements of your work depict sorrow and tragedy. Is that the way you see the world or is there an underlying message behind it?

O

The work that you’re mentioning is more of the personal works that I’ve been doing recently. I didn’t focus on detail before, because everyday I am on the field, where I would be taking shots of various objects or subjects for reporting purposes. Personally, I have always been attracted to something that is mysterious, something that has not been proven by science. When someone dies, they will never return to share his/her experience [of dying] right? So we can only question it. Death is an inevitable occurrence in our lives, I played around with that idea. I do this every time I finish reporting, where I spare the time afterward to take personal photographs that interest me.

A

A few months ago, you just held an exhibition titled “Soul Scape Road”, why was it held in Amsterdam and what was the story behind the exhibition?

O

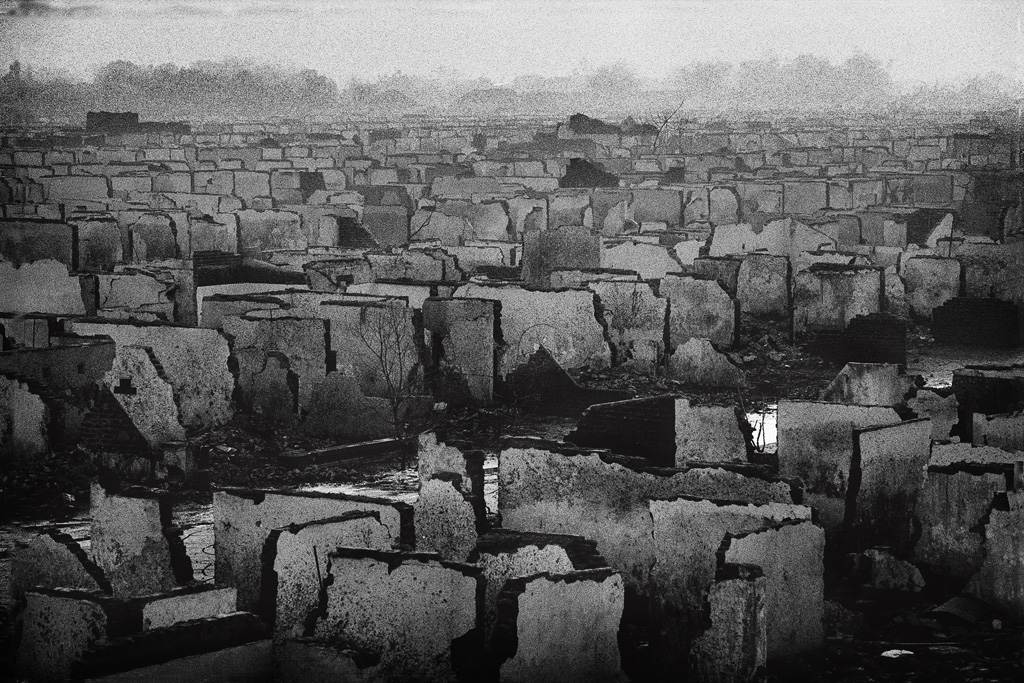

Actually the exhibition in Amsterdam was a continuation of the photography exhibition held in Salihara Gallery. The exhibition titled “Soul Scape Road” is a part of a trilogy that I made about death. There was “the Art of Dying”, which came after “Nyanyian Peripheral”, before was “Suara dari Angkor”. “Suara dari Angkor” was my first exhibition shot in Siem Reap, and was exhibited in CCF, Jakarta. I chose artefacts because I felt the close relation to the political situation in Indonesia, when I was working on “Suara dari Angkor” there was already an anti-Soeharto protest going on and people started grow tiresome of the government -a similar view to what was happening to Middle East at that time.

From my personal point of view, what happened to Indonesia was similar to the history of Khmer Kingdom and the history of the Kingdoms during Borobudur’s reign. So I tried to take part of the history of Hindu Buddha in Central Java and relate it to the history of what occurred in Jakarta, so “Suara dari Angkor” wasn’t only about Angkor, but it was related to the condition we faced everyday when President Soeharto exclaimed “Indonesia negara bahari!”. What I mean is, during that time, history was history, and you can’t idolize history, the future is meant to be filled by the next generation, to progress for people who live in the present. And I feel Siem Reap’s history is very similar to ours. They have always refered to the past until the Kingdom collapsed and I thought Indonesia was heading the same direction. Next was “Carnaval”. “Carnaval” resulted after Indonesia’s reformation, the title chosen after Soeharto’s fall. Ending with “The Art of Dying”, the work based on graveyards in France and is this sort of reflection of the post-reformation politics. Perhaps people do not have the same view as I, but the work itself is a platform to build discussion.

A

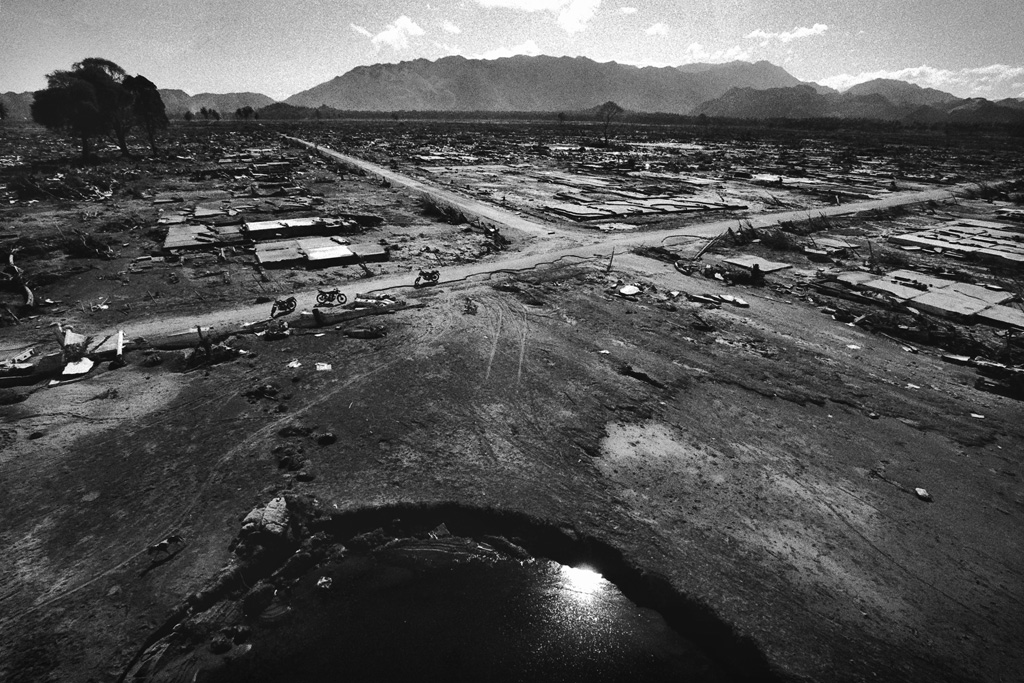

So it is more of an observation. How do you relate it to the Soul Scape Road Exhibition, didn’t that capture the lumpur lapindo events and the calamity in Merapi?

O

Yes, it was a personal observation that I did in Black and White, “Soul Scape Road” is actually a compilation of all the exhibitions above, highlighting the catastrophe that occurred in Indonesia and how the events were reflected. When I am reporting, I would capture images as a witness to tell people “This is what happened in point A”, for “Soul Scape Road” I captured the shots personally, so the images are my personal reflections of the news. Usually, the images are purely landscapes and objects, if there are people in it, their role in the picture is minor. My objective in exhibiting these images is to incite a feeling of ‘appreciating life’ from imagining themselves in that situation. That is rough idea behind it.

A

From the entire exhibition that you have made, can we say that it extends your disappointment and sadness of what is happening in Indonesia?

O

I wouldn’t say that, if you looked at the subject it may appear pessimistic, but I myself am not a pessimist. I always observe things from and an angle where I look for a solution. If we see things that are already beautiful it is already the solution in its imagery so I prefer to look elsewhere. It’s a process of digging deeper, before you talk about a plan see the negative consequences of it. My work, as you said earlier, is a depiction of what is currently happening. The fact is after our independence all people no matter the differences were supposed to be equals, but during Soeharto’s regime he was uniforming everyone. And now during this post-reformation era certain groups want us to adhere to the same agenda and point of views, and I don’t agree with that. So I express that opinion through my work, and the symbol that represent it is death.

A

You are well known as renowned Photojournalist in Indonesia, but not many may know what journalistic photography is. What is it by definition?

O

I don’t actually see myself as being well known because I’m just delivering my work; I am just a person that captures the photography. But photojournalists by definition are the people behind the scene, people behind the camera, working on the basis of delivering news visually, from a neutral perspective.

A

Is part of being a photojournalist just to deliver a message?

O

By profession a photojournalist is extending his voice through his/her eyes. He/She is a witness of events that should be passed on to other people. So photography here functions as a medium, its just at tool and it only stops there. Their objective is to share the news such as, for example, an accident on the highway. Once the news of accident diffuses visually, their job ends there. Sometimes, I wonder if their job only ends up to that point, what should they achieve afterward. That is when they should make their own personal work, and that is what I try to do.

A

Seeing the rapid development in technology, anyone now can have a camera on their phone, anyone can buy the latest Digital SLRs, and they can even spread news through their own camera. How do you respond towards this development in technology?

O

This era of technology advancement has really helped the world and my profession; because photography can now be sent in an instant online and people can receive news quicker. So the function makes it dynamic. But beyond the advancement and efficiency of what technology offers, you can’t idolize its existence, because in the end, photography is photography, no matter how advanced the technology may be.

Photography still needs to be directed by the person behind it. People with their common sense, ability, intellect, knowledge, background and so on, has to have control over it. So technology is only part of the equation. People who utilize photography, people who utilize technology still need to develop themselves, or they will only be part of the technology. He/She will never be a photographer with their own individual character and use technology as means to express themselves.

If you use your mobile phones to capture an image, a professional photographer would probably protest and say “that is not photography”, because he may think photography has to be done extensively with effort. But in journalistic terms, in citizen journalism, it is the right to capture the moment, be it accidents and other events by phone at that moment.

A

Can we say that as a photojournalism?

O

Sure, as long as the image appears from the photographer. Nothing loses from that.

A

You once stated that the public has a conventional way of seeing things, suppose there was a car accident, the public’s expectation would be an image of two cars colliding. How do you educate the public to see differently?

O

Right, so sometimes we want to see a momentum of an event in a literal fashion. If there were a protest, for instance, the police is arguing with the public, and the image would be of the two parties arguing. That is the verbal image, but it also proof that seeing is believing, what you see is the evidence. But there is a limitation to that, you can’t stop at that direct verbal image, you need to break the boundaries, photographers needs to develop and see the same event from a different perspective. Suppose, there is a riot, the photographer can instead capture the remains of shoes or rocks piled on the floor. This way, the aesthetics of photograph is highlighted through a richer angle which is much personal for the photographer.

A

We read that Galeri Antara was established with Arbain Rambey, Julian Sihombing,Yudhi Soerjoatmodjo and Gino Franky Hadi and at that time its objective was to spread the struggle for independence against Dutch colonization, that was the old objective, Is the ideology still the same, the objective to fight for freedom or has it changed over time?

O

In essence, the mission is still the same. But the time has changed. As you have mentioned Julian, Yudhi and the other Indonesian photographers formed Pewarta Foto Indonesia (Photojournalist Indonesia), an association of photojournalist in Indonesia that was established after the reformation. We made the organization to protect photojournalists in Indonesia, because after the reformation, the press in Indonesia had more freedom. So we knew, once the press was free we will face all sorts of pressure, we will face some sort of censorship, so that was what we are fighting against. Freedom of press should never be stifled after reformation. After reformation, one of the few things that succeeded was the freedom of press in Indonesia. We had freedom of expression within the ethics of journalism. That is what we are fighting for, and what we expect in the future. During the Dutch colonization, they were revolutionary journalists because the photographers and reporters had to join and side with republic. Reporters have to be objective, but during that time the only choice was to take side with Indonesia Independence movement. But time has changed. Now independent, we have to adapt to the times that have changed. Right now conservatives have a strong opinion; they want to force everyone to have the same beliefs And that needs to be fought against. And it can only be done with intelligent photography.

A

But there are still media who take side on a particular stance.

O

Right, there is. But it’s their right. Fact is, Indonesia is made of many groups and many parties. Indonesia exists because of those differences. Before we were independent our thoughts were “We may be different but our objective is the same, to fight for independence”, those differences became a form of unity for independence.

Currently, the many tribes and languages are proof we are diverse in race, in religion, and so on. This diversity should not disappear as we head towards the future. Ideally, we are all united towards reaching a common goal. With [Indonesia’s] independence, its citizens must have freedom over their destinies. Those values should be shared by the press.

A

But the fight itself…

O

Oh it’s not easy; it’s the same as the time Indonesian was fighting for independence against the Dutch. But now, they have to fight for independence from conservatism. Conservative groups have forgotten that Indonesia is based on Bhinekka Tunggal Ika (Unity in Diversity). Indonesia is made of many tribes. Why not live based on Pancasila? Everyone has the same right, to work, to socialize, and to do everything else.

A

That fight for independence seems like a never ending struggle, how do you fight for it?

O

Until now, we try to remind people through photography. The exhibitions we have displayed is based on plurality. In essence, we are the same. If you base it on the basic of Human Rights International that was built many years ago, everyone is born the equal and free. That is how it should be. You don’t need to express your disagreements, by imprudent matters like “Oh you’re not allowed to sing, because your skirt is too short”. Conservatism needs to be fought against. Not physically, because we are faced with groups who are stubborn in returning us to the olden days. We can fight it intellectually through photography, through reports, writings, to show the younger generation there is a long future to look forward to. You can’t expect unity to be achieved through conformity, people should have those differences while reaching for a common goal.

A

How about for photography, what is state of photography in Indonesia now and its future of photojournalism?

O

We are currently in the state where we are ready to take step forward. It’s time to be ourselves. Photojournalist are not supposed to hide behind the corporations where they work. Now there are many freelance photographers who have attitude, those who have character. Freelance is what can give them [who are stagnant] influence to move forward towards plurality. It’s not difficult to have the same objective. Why do you need to feel pressured? Why must there be all these stifling rules? Why are there so many ‘this and thats’ that will make Indonesia homogeneous? The main idea is that photographers that are developing should not stop at its corporation. Photographers should take a step further, to become a richer person, a richer photographer aware of their own existence, be themselves. Those people will be influence[inspire] other people. If more photographers and groups of photographers like these exist, the more photography will be explored and be seen by people as works of art, and that in turn will make it easier for the mission [progress] to be achieved.

A

How do you foresee the future?

O

In my opinion, the future still has to be fought for. There needs to be a motivation. A strong motivation to contribute in a change compared to no motivation to do anything.

—

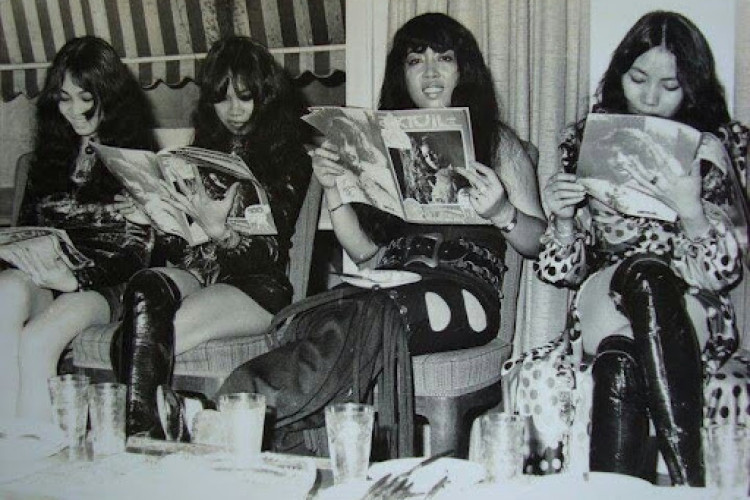

photography: Natasha Gabriella Tontey (1 & 4), Oscar Motuloh (2,3,5 & 6)

This interview was originally published on September 29, 2011.