A Passion for Percussion with Harry Murti

Mariati Galatio and Ken Jenie (W) talks to Harry Murti of Harry’s Drum Craft (H).

by Ken Jenie

W

Could you tell us how your interest in the drums began?

H

I began playing the drums in elementary school [1977], and after about 5 years I started to do it seriously – I formed bands, became a session player, etc, but I have always been interested in sound itself. Technique is important to study, but surprisingly most musicians aren’t very aware of the sound of the instrument.

Art comes in different forms. In visual arts you can see the colors, shapes, and sizes, but how would you describe sound? It can’t be seen, it can’t be touched, but it can be felt. I listened to a variety of music when I was younger – from Chick Corea, Saga, Yes, Genesis, Rush, to Casiopea – and what I learned was that a good set of drums can represent the sound of a genre. The sound of a good drum inspires us to play, its voice appropriate to the music we are looking to perform.

W

What made you decide to create drums?

H

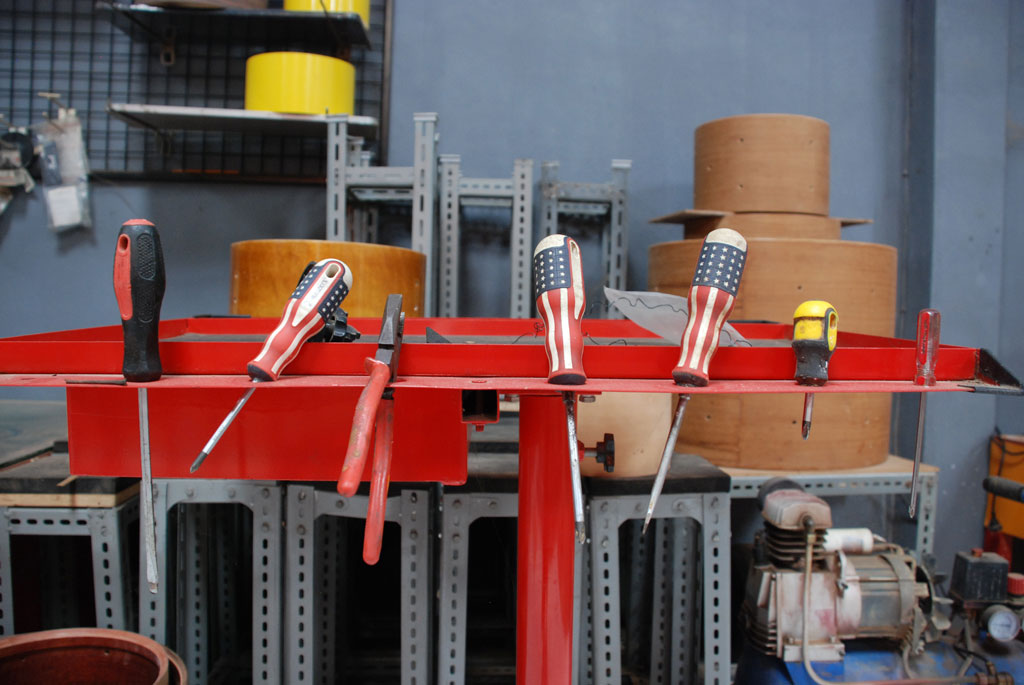

As most musicians know, a good instrument, in this case the drums, is expensive. When you go to a practice studio, you cannot emulate what you hear on records because it just wasn’t built to create the tone you are looking for – after all, they are generic. After researching, what I found was that the wood made the major difference. Different types of wood, the treatment, and parts make the sound. I, of course, wanted a good set of drums, but I neither had the money nor patience to save up – why should only people with an abundance of money be able to afford a great kit? There had to be a way for me to make my own.

I started studying the drums it self through magazines and speaking to the various people I met during my visits to NAMM [National Association of Music Merchants, a music tradeshow]. I am an autodidact drum maker.

All through college, work, and marriage, I was tinkering with making drums. It actually got to a point where I quit my job to continue my research. Work got in the way of my passion – this was when I realized that crafting drums was my life’s path.

I bought various drum parts and took it apart – I disassembled them, sawed the wood. My family was confused – why was I buying all these expensive drum parts and destroying them? It was so I understand the drums inside and out. I have a background studying aeronautics in college, so I had a bit of technical knowledge.

When I had a basic understanding of the instrument, whenever my friend’s drums needed fixing I would offer my services to fix them. This gave me an opportunity to further examine different grades – professional, performance, and level entry.

W

How long did your drum-studying process take before you started making your own?

H

Two years into it I wasn’t working, so to have an income I decided to create a practice studio – this way I can make money and focus on my passion at the same time. I already made playable drum parts at this time, but they weren’t up to the quality I wanted them to be. While building the practice studio I noticed that one of the construction worker, Mr. Dali, had great craftsmanship – he paid attention to detail and was consistent with his work. When the studio was finished I approached him and asked if he would help me make drums.

For 2 or 3 months I paid him to watch me made drums, then the next 6 months he started making drums alongside of myself until he was able to make them with minimal guidance. After about 2 years, we finally reached a point where we were satisfied with the final product.

From when I first started researching until Mr. Dali was able to create drum parts took about 15 years, and he has been working with me since.

W

As you were a drummer, what made you stop playing?

H

It was during the time where I was most successful as a drummer, I was invited to perform and was a session player, that I stopped playing the drums. I had to choose between performing and studying the drums, and I stopped performing.

I believe that as a musician, my ego would inadvertently translate into my drum making. I would give suggestions as to how the drum should sound like based on my taste instead of helping the customer develop theirs.

W

As your drums have been played by a large amount of musicians, do you sponsor individuals?

H

My ground rule is that I never give away my drums for free. Firstly it is because we are a small company, and we invest my time, money, and effort in creating the instrument. As long as I break even it is okay. Secondly, if we give our drums away for free the person would be reluctant to criticize out of politeness. When someone spends money to create a custom instrument he/she has the right to ask for their money’s worth, and the criticism help us make the best product possible.

W

Could you tell us what the process of working with a musician is like?

H

It all starts with getting to know the musician and their music. For example, I spoke to John from White Shoes and the Couples Company for a year before making his custom drum kit. We spoke over a period of time, I went to the band practices and tried to figure out how the drum kit will not only get the best out of John, but also how it can contribute to White Shoes and the Couples Company’s music. I believe there were about 3 revisions before we finally made the right drum kit for John.

W

We understand that you use Indonesian wood to make your drums?

H

If I were to use North American or European wood, what would make me different from drum makers from that region? They are already at the top of their class and understand the qualities of their raw products. I have to make my own type of drums.

I wholeheartedly believe that the wood in Indonesia is excellent. Most instruments are made with wood found in North America, Maple, and Europe, Birch. Now the alternative is Mahogany, which is actually mostly found in tropical countries. The instrument making companies wanted to explore the possibility of different type of exotic wood. They went to Africa, other tropical countries, and finally in Indonesia they found a plethora of wood. One of the highest-grade wood is from Indonesia – Makassar Ebony. Let’s say Maple cost about 2500 dollars per-cubic meter, the Makassar Ebony would be about 35,000 dollars per-cubic meter in the international market. Unfortunately, because it is not well protected it is subject to a lot of illegal logging. There are plenty of other exotic wood in Indonesia as well.

W

Have you began selling your products abroad?

H

My customers have been international for at least 10 years now, and people know my drums from word of mouth. For example, Dion Parson visited my home looking to buy a set of drums. I asked him why he would go to me to make a drum kit, I mean, he lives in New York as a jazz player where he can find a great selection of drums. He replied that as a professional drummer he doesn’t worry about his technique, but he needs to develop his own personal sound. New York has plenty of maple and birch, he wanted a sound that was more exotic. We talked for a couple of days and when we agreed on the kit he went back to New York.

W

Since you are based in Indonesia, how does an international customer know exactly what he/she is getting?

H

That is why we have to talk for a couple of days. We talk about the sizes, the type of wood, etc. Although no drum sounds the same, we can adjust the parameters to create the sound closest to what the customer wants. Beyond the drum making, the drummer will take some time to learn the sound and adjust to the drums.

W

You have created multiple signature drums, I take?

H

We have been lucky enough to have many people play our drums. We provide the drums for Java Jazz so we have had everybody from Stevie Wonder’s band, Fourplay, to Manhattan Transfer and Professor Dr. Leonard King Jr playing. Outside of jazz I made drums for Phoenix’s performance in Jakarta. The band uses a drum size that is unconventional, and Soundshine [the organizer] said the band was persistent about getting that size. So I took up the challenge not knowing what it would sound like, and when I was finished I was amazed at the sound it produced, it was beautiful.

W

With your success as a custom drum maker, why not create a line for Harry’s Drum Craft?

H

I have had multiple parties asking me to join a partnership in making mass produced drum kits. Financially speaking, it is quite attractive because of its potential reach and profit, but I am reluctant because this sort of venture would make me focus on the business aspect. I had to make a choice between business and doing on what I love – I chose the later.

W

Aside from founding Harry’s Drum Craft you are also involved in creating Jakarta Drum School, could you tell us a bit about how you established it and why?

H

Jakarta Drum School is a center where we can share our knowledge. I have always wanted to share what I know, but what I know is quite limited. I invited some of my friends who studied music abroad – Berklee, Percussion Institute of Technology, Drum Collective – to meet and I told them the school’s concept. I explained that most drummers aren’t as lucky as they were, and that their knowledge could be shared – that would be their legacy.

Through the school we created a program that would facilitate the growth of the students through a rigid but individually focused curriculum. It is wonderful to see the students successfully follow their passion in drums. Most of our students perform on the big stages, become “go to” session players, and those who continue their study abroad have a 100 percent-success rate in passing their examinations – we’re very proud of that.

Music is still considered a hobby in Indonesia, and Jakarta Drum School would like to promote the fact that art is a field one can professionally pursue. There has to be an understanding that there are alternative professions one can learn if he/she has the drive and discipline.

W

You also founded a program called Rhythm and Groove Music Camp, an intensive 1 week program where participant observe and work with Industry professionals. How did this idea came about?

H

This idea came about while I was in Singapore in the early 2000s. During my visits I met a number of great musicians, and one of them was a senior bassist named Din Safari from Jive Talkin. We traded ideas and philosophies, and found that we had a commonality – we both felt that musicians were given a gift and that gift should be shared, that was the beginning of me and Din Safari establishing Rhythm and Groove Music Camp.

The program is inspired by Din’s experience participating in Victor Wooten’s Music Nature Camp in Nashville, and other music camps. He explained that those programs he went through were inspiring, and we wanted to bring those kinds of programs to our region. We knew that there were many expert musicians from Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia, etc, that could help guide aspiring musicians. Masters such as Yance Manusama, Barry Likumahuwa, Taufan Goenarso, Euntaek Kim, and Amelia Ong have participated as teachers in the program.

W

Regarding the program’s 6-day period, could you tell us what the participants achieve in this relatively short time?

H

Through our basic concept of “understanding, share, and respect”, we have a formula that we would like to ingrain in our students:

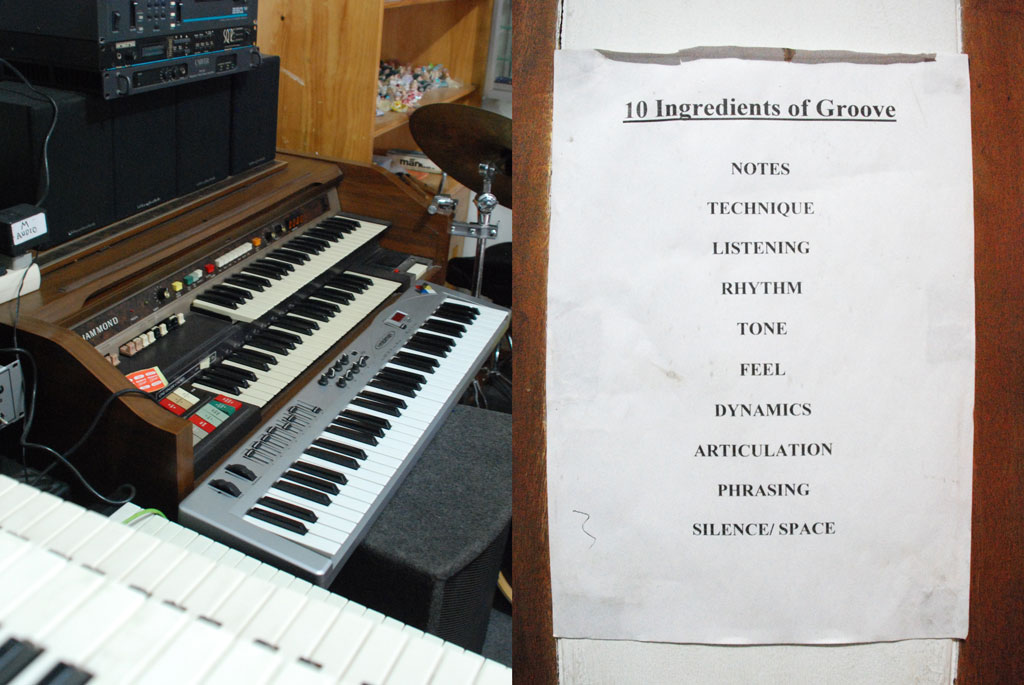

The Ten Ingredients of Groove

1. Notes

2. Technique

3. Listening

4. Rhythm

5. Tone

6. Feel

7. Dynamics

8. Articulation

9. Phrasing

10. Silence/Space

With a short program we aim for campers to fully understand the root concept and essence of music, making them more confident in their performances. In the end the development of skills depend on their own willingness to practice, in Rhythm and Groove Music Camp they learn the essential tools to improve their musicianship.

Our camp’s schedule involves the campers with everything from games, practice sessions, class exercises, jam sessions, to coffee breaks and meals. The magic, though, happens when spontaneous, fun, and memorable moments inadvertently happen through out the day – inspiring stuff. Our teachers seek to help campers find their own path in playing music through tips and sharing their experiences.

W

Thank you very much for the opportunity. Any final words for our readers?

H

I am passionate about my work, and have found my “bliss”, so to speak. There are moments in the creation process that I mentally get immersed in. I can tell that I have created a good drum kit in that moment of bliss.

I create based on a concept and passion. Everything from Rhythm and Groove Music Camp, Harry’s Drums, to Jakarta Drum School – I did not make them for the sake of money, these are all dreams of mine that I was fortunate enough to achieve one by one.

Money is important, but it isn’t everything. Having passion and achievements is the legacy you will leave behind.