Conserving the Environment with Nadine Zamira

Athina Ibrahim (A) visits Nadine Zamira (N) at her house

A

What’s your background, and how did you get into this world?

I

It was a very natural transition for me. Since I was a child, I grew up in Colorado. And if you know what Colorado is like, it’s known for its natural landscape and natural infrastructure. Even in school, environmental education was already integrated into both the educational system and society in general. And the activities that most people did were related to nature. Our apartment even required that we engage in urban farming. And then, in school, classes were mostly held outdoors – especially experiments. My family has always encouraged us to be more sensitive towards nature. All our vacations would be nature escapes. All the experiences that my parents pushed us towards included exploring caves, hiking, and bird watching. We even went to llama farm (laughs). We interacted with the environment and animals. All of this was possible because it was very accessible where we lived back then. So that was a very pivotal point in my life. It became the foundation of my life. It stuck. But here, it’s difficult for us to get exposed to those kinds of things. Here, it’s the opposite. The society and the schooling system don’t emphasize those values. But at home, my family still tries to live by those values.

A

Did this influence the decisions that you had made?

I

Yes. And it’s been a long process. When people say, “habits start young,” they’re right. Because we’ve been encouraged to lead this kind of life since we were kids, we’re used to it. A lot of people have started to talk about the “green campaign,” and we’re like “Oh, that’s what it’s called?” For us, it’s always been our way of life. Things like the act of saving and waste management; things like that, we’ve always known how to deal with it. Respecting nature has always been a part of our upbringing.

A

What made you decide that you want to be completely involved in this field? A lot of people consider this as their way of living, but they pursue other things.

I

If you ask any conservationist or environmentalist, almost 80 to 90 percent of them would track their passion to their childhood. There must have been some moments in their life when that love was nurtured. That’s the statistics. When I studied International Relations in college, I ended up studying things that were related to the environment because it’s such a big part of me. As I learned more about the environmental conditions in Indonesia or in other parts of the world, I realized that it’s my role. It’s the career that I knew I had to pursue. I’ve always known it, but I just grew into it. I was kind of fulfilling my destiny. I took my masters in communication, but my projects and thesis were all linked to the environment. It was like a calling. I was just fulfilling my calling. Nothing interested me as much as environmental issues. After I graduated, and was looking for my first job, I wanted a working environment where those values were also applied. So I was thinking of companies that applied the same things. Through destiny (laughs), I found Body Shop and you know how loud they are on social environmental issues. So I got accepted and worked there for three years and I knew that I wanted to be in this field.

A

So what were you handling in Body Shop?

I

I worked in the CSR department, but at Body Shop, they don’t call it that, they call it the “Social and Environmental Issues” department. I was on the team that was in charge of all their campaigns within and outside the store, staff training, and green office programs, and basically anything that had to do with environmental content. At Body Shop, I gained lots of connections and learned a lot about the corporate world.

A

After that, you joined Miss Earth, right? How did that happen? Did it happen during your experience at Body Shop?

I

Yes. The good thing about Body Shop is that they encouraged personal passions. So I’ve been experimental with competitions (laughs). I found that it was way for me to learn new things fast. Fast knowledge, fast networks. Why did I join Miss Earth? I felt that I needed to be consistent in what I pursue. I didn’t join Miss Indonesia and all the other pageants because I thought that this one supported my cause best. So Body Shop supported me – they let me leave for a month (laugh). But in the end, it was a turning point for me because I thought to myself: this public role isn’t what I’m supposed to be doing. The pageant actually had a very small impact on my cause. And what’s a title, anyway? I knew that there was a bigger role for me to play. Throughout my college and working life, I’ve always been involved in several volunteer groups and environmental NGOs. I was pretty active in the community. When I made the decision that I wanted to do something my self – that was another thing; I guess I also had an entrepreneurial calling where I could set up my own thing. I knew that I wanted to be in the environmental field, but the challenge was how to make all this activism profitable?

A

Right, because you need to make a living.

I

Of course! (laughs) That was the challenge. Because when you look at most social-environmental issues, they always fall into the category of charity, pro bono, philanthropy, etc. When actually, it goes against the whole concept of sustainable development. When you’re talking about sustainability, the economic pillar also has to exist. I didn’t just want to be an activist. I also wanted to make a profit out of it. But at the same time, I also wanted to make the same impact.

A

So you formed LeafPlus? How many people are involved?

I

Yes. Right now, we have nine. It started with just three people. We first met at one of the communities, and we shared the same vision, and wanted to make a profit of it. At the same time, we saw the need for an organization. Even when we were still mostly active in the communities, companies would come to us who wanted to know how to make environmental programs and CSR programs. They wanted to know how to make programs that were sustainable, who to work with, etc. There were so many questions. No, CSRs are in high demand. But not all companies had teams that were capable of handling such issues. So we thought, Ok, let’s make an agency that only handles CSRs. But after we started, the field was actually so much broader, and expanded to environmental communications. A lot of people asked what we were actually doing.

A

So how would you explain environmental communications? It’s practically rare.

I

It is, it is. In Indonesia, we’re one of the first agencies to do this. It was a challenge. The field is totally different. We’re offering a new service, so the market isn’t as developed as that of products. With products, you can automatically segment your market. Things like that are still vague in my field – or at least, in Indonesia – because in other countries, such as The United States and across Europe, they are very developed. So we ended up learning a lot of things along the way. How would I define my company? To make people relate to it quickly: think of a PR or advertising agency. That’s basically us, but we’re PRing and advertising/marketing is the environment. That’s how I would explain it. The products that we’re selling are our issues and causes.

A

How do you PR that? It’s very broad; it could be anything. With products it’s tangible and physical, so how would make people understand your “products”?

I

What we’re offering is a service. What we’re promoting is something intangible, but the business model is no different than if we were selling products. Throughout history, people have already been marketing the environment, but it’s failing. If it were successful, we wouldn’t be where we are right now with all the destruction. The approach has to different, and it can’t be done with the usual branding or advertising when you’re just doing blatant selling because with the environment, it gets a bit tricky. You have to communicate different things at the same time. Up until now, the approach has been – as we call it, the “lost message” – “selling the degradation,” “the loss” – that’s what’s being communicated. But in reality, what’s more effective is the “love message.” For me and everyone else.

A

The way it created a bond when you were younger.

I

Yes, that’s what was being communicated to us as kids. We were exposed to the beauty of nature. So actually, there are certain tricks to the field, to the industry. All this time, the approach has often been wrong. When companies want to communicate their CSR or environmental programs, they still think in terms of marketing. In the end, people will see that they’re not sincere – just another PR gimmick.

A

So it’s just advertising?

I

Yes, it’s just advertising. And what’s the result of all that? Is it measureable? Is it not? Yes, I’m doing a lot of PR advertising, but what I’m promoting is the environment. I have to be a good PR for the environment. I have to sell its good points. I’m helping my clients who are from the government, the corporate sectors, and foundations. I help them to PR the environment in the right way.

A

So could you give an example of the projects you’re handling?

I

It’s been interesting because we’ve been working with various sectors. There are foundations, communities, governmental institutions, and corporations, too. The most recent one is “Hidden Park”, a project commissioned by the government. So the challenge was how to communicate the issue of spatial planning so that it’ll be interesting for the public. We raised the issue of urban parks because it doesn’t get enough attention in the media or the general public. We don’t think about going to parks. We think about going to malls, cafes, restaurants, and whatnot. Most people don’t even know that they’re accessible.

A

There was a park around Senayan that I’ve never heard of until someone recently told me about it.

I

Yeah. According to Dinas Pertamanan, Jakarta has almost 1000 parks – ranging from “taman kecamatan/keluharan” to “taman kota.” There’s a hierarchy to them, too. But yes, there is about 1000 parks altogether. Then comes the question of why people don’t know about any of them. Why don’t people utilize them? So why did we call the campaign “Hidden Park”? Because it’s not only the location that’s hidden, but the potential is also hidden. When we, at the communities, talk about urban parks, the same concerns come up over and over again – they’re not comfortable, they’re not safe, and they’re just not accessible in general.

A

So there are so many layers that you need to take care of. There are 1000 parks, but they’re not maintained well. How do you deal with all of this?

I

We had to talk with people from the regional government. Their biggest challenge is to increase the number of urban parks. There’s actually an article (undang-undang) regarding urban planning that requires 30 percent of the city to consist of open, green spaces – that is, in the form of urban/city parks. They admit that they don’t think of the value of urban parks, so they don’t think about the target audience – like who’s going to utilize the parks. They think that as long as a park has grass and trees, they’ve done their job. But if you want to make a part that’s dynamic, you have to think whether or not the facilities that are available will be suitable for the target audience. If the target is children and families, you must have a playground. We haven’t reached that level yet. We’re still trying to achieve this 30 percent target. And that’s one of our criticisms towards the development of parks. The system is very centralized – from the management to development of parks. They’re all handled by Dinas Pertamanan. In Singapore, it’s a collective endeavor. There are people from the community who regularly use it, and then there are people from the corporate sector who can help finance the whole thing. Even people from the creative communities get involved because they also think that it’s important to make parks that are attractive. Here, everything is very centralized. What we tried to with “Hidden Parks” is to encourage people to demand for better parks. It was actually quite effective because people started to notice parks, and how they’re all in very bad condition. We become facilitators. Even if people do want to fix public spaces, they don’t have access. But they’re also confused by the fact that there are facilitators because they’re just not used to them. Somebody donated a bridge. “Hidden Parks” was successful also because we managed to attract mult-stakeholders. Companies and our other clients also helped. They donated wi-fi, segregated trash bins, bicycle racks, plants, etc. In the end, it became a model of cooperation – the way it should be. And communities started coming. We made lots of fun activities. We screened movies, held music performances, etc.

A

And there were different communities involved too?

I

Yes, there were 26 communities. They all did different things. Some of them told stories, while others did urban farming. There were also lots of things for children. All we did was drive them to the park. Do whatever you’re doing, but do it at the park. During the campaign, we could really see the difference. The parks became came to life, and people realized that it was important to keep them clean. Companies saw these parks as places they could invest in – and they’re all in their own back yard. Sometimes, when people make CSR programs, they think too far – about planting trees in some faraway place, etc. But it’s actually easier to start in your immediate surroundings.

A

So you’re aiming for quantity of adding more value to the park, while also maintaining the quality?

I

Yes, and in the future, we really want to improve the management of public spaces. It’s such a waste. We have amazing creative potential in our creative communities, but they’re not utilized. There are so many things that can be done.

A

And talking about communicating, when you communicate something, there’s always so many levels that you can expect people to achieve – people can be aware, or they can just act on it. In your perspective, which levels do you actually want to achieve?

I

The mission of all environmentalists is to change behaviours. It’s actually that. And of course, everyone knows that the psychological process that leads to behavioural change is very long. First you have to be aware, then you have to be knowledgeable, then you have to act upon your knowledge, and then it has to be a habit. Actually, our goal is to put ourselves out of business. Right now, it’s not that we’re not succeeding, but have to be more critical towards the approach that we use to protect the environment. Environmentalists tend to be very forceful, and many talk in a way that people don’t really understand. And the “loss message” is the one that’s always being communicated – this is dying, or that is extinct.

We found out that, according to basic psychology, human beings aren’t rational. When we say that a certain species is endangered, the rational response would be to save it. But people don’t think like that. People are more emotional than rational. So the effective approach would be to engage them emotionally. And this also applies to conventional branding. People sell products that way, too. They sell emotions, and that is what we have to learn to do, too. Branding the environment, yes, but also making an emotional experience. And it should be easier. How can there be a cult for Nike products/sneakers? It doesn’t matter how much they cost, they’d but them. But when it comes to something that’s actually closely related to us, people aren’t attached. It’s that attachment that we need to create. We have to be more exposed to the outdoors, to the environment.

A

So how do you take that? I mean, people who don’t have that bonding at all? They’ve already reached a certain age, so how do you take them out of that so they’ll to get a certain amount of exposure – or at least to build that emotional connection?

I

There are lots of ways. One, we have to talk their language. That’s why I realized that it’s important to cooperate with people who already understand their language. I have to be allies with branding people, marketing people, and creative people so that we can find what already works there, and then try to communicate it to the public. So I think that it can start with products. It seems counterproductive, but it’s actually not. Take “aspirationals,” for example. They’re people who follow something because it’s a trend, because they get a certain prestige out of it, and it makes them feel good. These people are actually the biggest audience I want to change because they’re the ones who consume a lot. It’s their lifestyle that’s caused a lot of environmental degradation; not people like me who are already aware. To communicate to them would be to communicate through the things they’re accustomed to doing – through their consumer behaviour, through their shopping behaviour, through the products that they buy. With a combination of good design and good marketing strategies, they will pick up on it. I think one way to do it is to communicate through products. And such people would buy a certain product not because of environmental factors, but because it’s cool, it’s well designed, it looks nice, it’s functional, and, hey, it’s also environmentally friendly. I think a lot of people nowadays want to engage themselves in a cause, so that it also becomes a status. And this has been scientifically proven.

A

So how would you make sense of this generation? A lot of people talk about “green” this and “green” that, but for you what does that mean? Everyone just talks about it, but do you think there’s any impact?

I

Personally, I would be someone who you would call “biophilic.” It’s a term to describe people who love the environment no matter what. The environment is what I base my decisions on, and it’s what governs my thought process. But not everyone is like me. Some people tend to be “anthropocentric.” They’re very human centric – “my needs” centric. And we have to accept that. People aren’t rational when they deal with big issues. In fact, they tend to think that it’s too big for them to have a role in it, and they end up becoming apathetic. What’s happening now is that the word “green” has become a catchphrase. It’s a buzzword. I actually think it’s a step towards the right direction if you want to capture the mass, because that’s what we want to do. We can’t force people to suddenly become hardcore environmentalists. We can’t force them to love the environment all of a sudden. Like I said, the approach has to be a lot more mainstream. One reason why this trend is increasing is because it’s entered the products that people wear, and the food that we eat. It’s been translated into a language that we all understand. It’s a good thing because it means there’s a momentum. We have to think about how to take advantage of this momentum and get the right messages across and to result in the right behavioural changes. In my activist frame of mind: stop talking, and do something. But not everyone can do that right away.

A

Maybe they can just say that they’re contributing because they’re buying a certain product, but their whole lifestyle has nothing to do with contributing to the environment. Where’s the impact in that?

I

I’m very critical towards things like that. But I have to see the bigger picture. What is our goal? Our goal is to create a mass effect. Because if you’re talking about the grand scale, you want this mass effect because this is what will change how industries do their things. It will change the way governments are making their policies. It’s this mass pressure that will change those things. It’s not a group of environmentalists, it’s not one or two people demonstrating somewhere, it’s this mass. So that’s our challenge now – how to take advantage of the trend and serve our cause. In my field, what we’re doing is pretty rebellious because I’m trying to make the environment profitable. I’m trying to combine the environment and economics. Many activists are very critical towards us because they think the environment isn’t supposed to be quantified, and that it should come from the heart. All of which I understand, because that’s how it all began for me. But in the end, you see all the numbers. Degradation is caused by development, by consumerism, by lifestyles. When I was a child, I thought that being an environmentalist meant living in the jungle and saving one orang utan at a time. But my biggest challenge now – my biggest jungle – is here, amongst the modern people and their lifestyles in the city.

How would you make sense of the fact that people are going back to basics? More people are going for organic food and a healthier lifestyle. But they have this idea that going for a healthier lifestyle is actually more expensive. For example, the organic food at the markets is more expensive compared to regular vegetables. Or to design a green house, they say it costs more than designing a normal house. So people still consider all of these things in monetary terms.

True. And that’s okay, because it creates a push for eco-products to be more competitive. Why is it expensive now? Because there aren’t enough demands. If this wave of change that is happening now can make more people buying eco-friendly products, the price will decrease in the future. And that’s what we’re hoping for.

A

Does it make it not accessible?

I

No. There’s a theory of the stages of commitment. The first stage would be to alter a habit. Second, you’ll start sharing your knowledge, and you’ll start to influence other people. There’s a third one that I forgot (laughs). And the fourth is wanting to invest. If you’re really committed, you invest in the right products, and a better lifestyle – even if it means you’re spending more. So, that’s one way of looking at it. I guess it filters people who are really committed to their green lifestyles. Another way of looking at it would be…how do I put it…well, I guess it’s still an ongoing process. We’re still at the first few stages. But then again, it’s not always expensive. What makes it expensive is probably the technology. But there’s always a way around it. A lot of my friends buy really expensive imported fruits to make their green smoothies.

A

Which is ironic, because it increases the carbon footprint.

I

(Laughs) Yeah. They buy broccoli imported from somewhere. And I’m like, okay, if you want to go organic, you can still do it in an economically sensible fashion. Just buy local products. If you know where to go to buy these products, that are much cheaper because traditional farmers don’t use pesticide, you can easily get them. You just have to look for it. A lot of people misunderstand the meaning of “organic” because they don’t see the bigger picture. People don’t think about the costs that imported products entail. And my house is not more expensive than other houses. But because we understood the concept of maximizing sunlight and ventilation, we built it according to the environment – which is a tropical environment. You’re not supposed to be dependent on air conditioners. You’re supposed to make use of the natural environment. It’s not big changes. I think anyone can do it. We also made our own composting system, as well as our water-recycling system. It’s not that something that has to be that expensive.

A

You talked a little bit about CSR, and how they’re related to most of the companies you work with. What do you think about it? A lot of the companies are really profitable. For instance, a cigarette company may aim to give back by creating a public school. Do you still think that their CSR is still good?

I

It’s a very grey area. And very debatable. I think nobody agrees on that. Even my own company isn’t so comfortable handling a cigarette company or a mining company. A lot of CSRs are investing in things totally unrelated to their industries. So for example, if a cigarette company invests in, I don’t know, education, for example..is actually okay. And their foundation is actually really good. But ideally, the first approach should start in their own backyard. That’s where they should start cutting down on their impacts. If the changes start from their own industry, you’ll immediately feel the difference. If an automobile industry starts using recycled tyres, it would cut the costs needed to buy tyres. They can just reuse old ones. This is how CSR should begin; from the inside, not outsourcing.

A

I see. But I guess many industries still haven’t reached that point.

I

Right. Because they think that doing so would actually increase costs – in the sense that they would have to redesign their products, and they’re not comfortable with changing the ways that they’re already accustomed to. They’d rather try something completely different. That’s our challenge. I’d love to work with a mining company or a cigarette company, because it means that I’d be triggering change in those industries. If they could change the way they produce their goods, we can finally achieve the green economy that everyone is talking about.

A

One thing that really bothers me is how easy it is for people to litter here. And all of this garbage causes floods, and the environmental degradation of the city. But things like that have turned into a culture. How do you think you can change the next generation? What sort of education programs do you think can encourage kids to throw away their garbage in the right place?

I

Educational programs have to be continuous. There are many people trying to go into the educational sector. Green schools, and communities/organizations operating in schools – mine included. Not that I’m trying to put the blame on others, but I really think that the government needs to invest in something more systematic because we don’t have a recycling center in the city. There is no recycling infrastructure. Everything goes straight to the landfill. There’s just no system. But in the end, you encourage anyone who wants to listen. You educate your children, etc. But to make an impact that will change the next generation, you need a system that can encompass something of that scale.

A

There was this one show on YouTube that compares the life of a trashman in the UK and Indonesia. And you can see the striking differences. Here, you just dump everything together. There, the habits start from home.

I

Right. We separate our trash here. But because the system is not in place, we make our own system. We have our own composting bin. And then we give the non-recyclables to the scavengers. They recycle plastic bottles and paper. But to get more people on board, this process should be easier to do. We need a system. I think the culture of not caring, of thinking that someone else is responsible for their trash, is a really bad mentality that bad that developed countries don’t have.

A

We’re kind of spoiled then. (laughs)

I

Yeah, we are. There’s an anthropological explanation. Back then; Indonesians ate things that were packaged with leaves. So culturally, we threw our garbage just about anywhere. And it was okay, because leaves are degradable. But now, everything is plastic. There has been a shift in the materials, but not the mentality (laughs). In Ciliwung, the riverbanks are filled with plastic trash. It’s a riverbank of plastic.

A

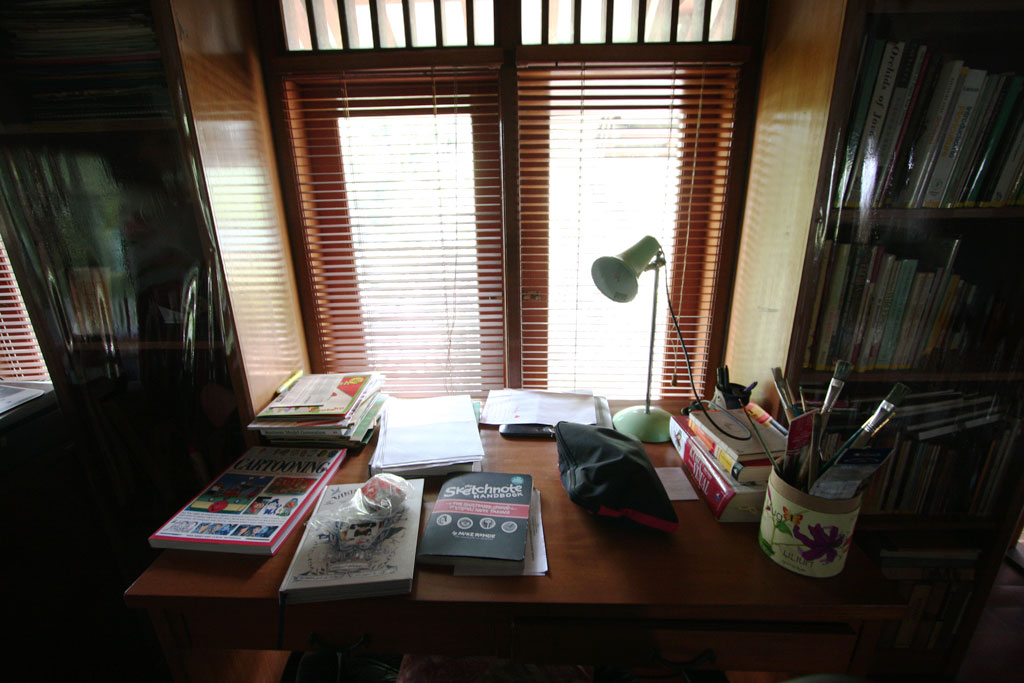

People know you as someone who focuses on environmental issues. Do you have any personal obsessions – like particular books that you’re reading?

I

You know what? I have always been artsy – and my sister, Tania, too – so when we were kids, we’d try all sorts of courses. We designed, painted, and sketched. It stuck until now. I love design, even if I don’t practice it. When I was applying to universities, I wasn’t allows to take design. But then my sister could. I’m so jealous! I wanted to do that (laughs). Because I’m the first child, the expectations are pretty high. (laughs) I really wanted to study fine arts at ITB.

A

What is it that you like from design?

I

I like anything that is aesthetically pleasing. I guess that comes from nature, too. By observing nature, you understand beauty. I think that applies to a sense of art – an appreciation towards art. I love fine arts in the form of sculptures or paintings. I love museums. Now, I’m excited about how graphic design in developing – the style, and how products are becoming adorable just because of the design! It’s like, this serves no function but it’s so cute! (laughs). So, that’s something I still follow. I read Tania’s design books, and I look out for it. Most of my readings are still related to what I do – environmental stuff. That’s it. I guess my other passion would be travelling. I try to go somewhere new and exciting every year (laughs).

A

So what’s your next step? What do you want to explore after this?

I

Um, I want to go into products. I really do. I want to go into eco-products.

A

Do you have anything specific in mind?

I

Yes. Locally grown organic vegetables. I’m still researching, so I don’t know if it will work or not. In New York, there’s this place called Green Gotham. There’s an old abandoned warehouse this man turned into a nursery in the middle of the city. And they produce organic vegetables and they deliver them, too. Imagine how profitable that would be in the city! There’s a growing demand for it because imported stuff is too expensive. We don’t need that.

A

Looking back, do you think you are where you wanted to be back then?

I

I think so. I managed to maintain my career path. I’ve always wanted to do something on my own. I’ve built my own company. So yeah, I think so. Of course, there are still so many things I want to do. But an environmentalist’s job is never done.

A

So it’s an ongoing process?

I

It’s an ongoing job. (laughs) There are so many different aspects. I’m always thinking about the next step.