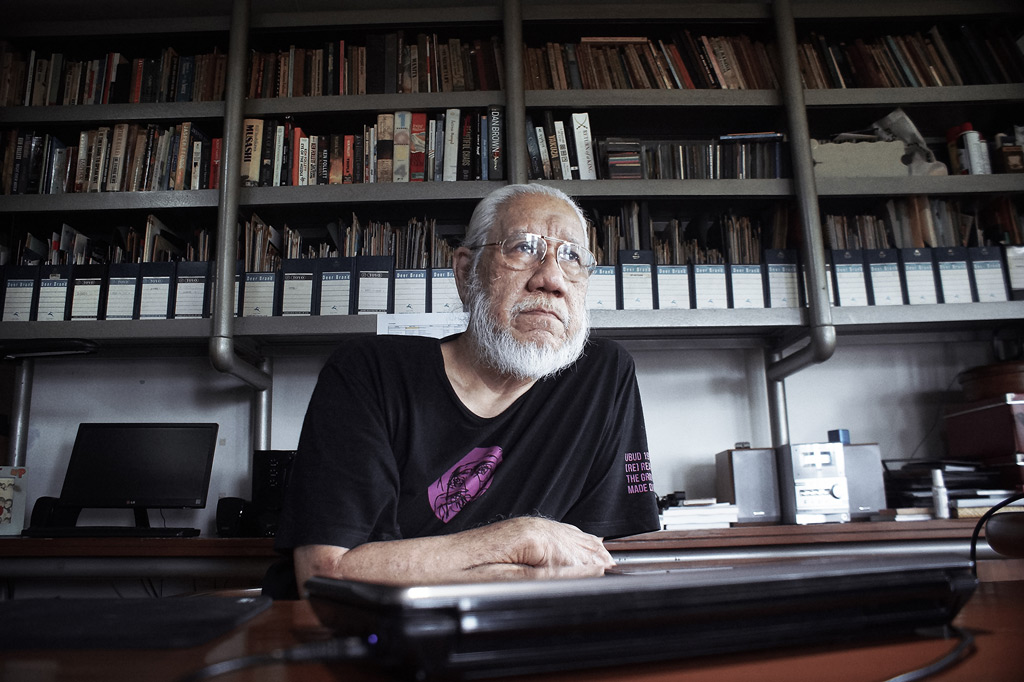

Art & Curation with Jim Supangkat

Muhammad Hilmi (H) interviews art curator Jim Supangkat (J).

by Ken Jenie

H

You are one of the initiators of the “Indonesian New Art Movement” what was the reason behind your defiance towards the old art?

J

I did mention the “old arts” during my statement regarding the New Art Movement. The old arts put academic restrictions on the teachings in all fine arts colleges in Indonesia at the time. These restrictions put limitations on painting, sculpture, and graphic design. Paintings, for example, must be two dimensional, and sculptures must be three dimensional. Paintings whose surface is too protruding, or sculptures that were painted were considered questionable.

The New Art Movement was an academic rebellion towards fine arts universities in Bandung and Yogyakarta. The New Art Movement was an art that smashes the academic limitations mentioned earlier. The New Art Movement even gives freedom to the shapes and form of art – creating art that aren’t limited, for example, to the use of high materials such as canvas, Rembrant paint, marble, metal, or hand made paper. So people can create art from ready made, even used material. I have created works such as this since 1972, during my studies.

Today’s contemporary art can be considered ‘new art’ if seen in the context of The New Art Movement. In 1975, the term “contemporary art,” with the definition we know today, hasn’t spread even in Europe and the United States.

H

What made you decide to become a curator, an art critic?

J

I made the decision to become a curator in 1990 after being involved in ARX (Artists Regional Exchange), a contemporary art forum in Perth, Australia in 1989. At the time, I realized that there was an emergence of opportunities for Indonesian artists to enter the art world through Australia. This forum helped me realize the need for the curator profession during that time where there were no curators in Indonesia, and this void must be filled.

In 1989 I received information by chance regarding the shift in the meaning of the curator in the United States where a number of museum curators left the museum and proclaimed themselves independent curators. They created a new understanding of the term curator.

Believing that there was a chance to enter the world forum was open to Indonesian artists, and the interest about the progressive understanding of the curator profession, I and the late Sanento Yuliman decided to become curators. My guess didn’t miss, during the decade of 1990, Australia and Japan focused their attention on Asia’s contemporary art development, and as we all know, the two countries’ programs became stepping stones for Indonesian artists to enter the international art scene.

H

What was the transition from being an artist to a curator like? Did your working experience in two media, Tempo and Aktuil, have an effect and helped during the transition?

J

I did have my reservations before deciding because I would have to leave my artist profession if I wanted to become a curator. As an artist of course I had the wish to appear on the world forum, especially since my collaborative work with three artist friends in ARX, 1989 gathered some attention in Perth. The piece defended those who suffered from AIDS which, at the time, were reviled, ostracized, and treated like pariahs. As we all know, in 1991, the world started to embrace those who suffered from AIDS and infected by HIV.

But I finally decided to become a curator and stop creating art. In actuality, being both an artist as well as a curator isn’t impossible. There are many countries where artists also work as curators, but for the context of Indonesia, I felt that to become a curator I had to leave my artist profession to not be tempted into corruption.

There are, of course, other considerations behind the decision. Since my fine arts studies I have been attracted to the thinking and theories of fine arts, and am accustomed to writing my thoughts. My familiarity with writing brought me to Aktuil, Zaman, and Tempo magazine. You are right, by working in mass media, particularly Tempo, my ability to write were honed.

H

In an age where everything is instant, anybody can be anything, including becoming an artist. Does this instantaneity apply to being a curator?

J

The independent curator profession is no longer tied to the image of the movement where the term first appeared. In today’s development, this term is defined by the literal understanding of the predicate “independent,” freeing the curator from the public responsibility. So now with any practice, these “independent curators” cannot be held accountable. In China, most independent curators I happened to meet are art dealers.

In the midst of these developments comes awareness that museum curators are curators with a public responsibility because they work for a public organization and their work are associated with a society’s culture and civilization. Because of that, museum curators must have a strong code of ethic. This responsibility also helps them measure their abilities. Chief curators in museums are the best curators, measured by the knowledge they have mastered.

Independent curators do not have such responsibilities and aren’t demanded to have such abilities. That is why anyone can become a curator. Whether or not they are popular depends on who hires them. In the art market, the less-determined curators are the ones that are favored because they can be included in conspiring in the fine arts business.

In Indonesia, where there are relatively no public museums, curators are generally independent. But when I started my curatorial profession I decided on taking a position and becoming an independent curator with a public responsibility, even when there wasn’t a pressure to do so. The consideration was that in Indonesia there were no museum curators, so there were no curators with public responsibilities. As far as I know, most curators in our country took the same position.

H

What is the role of a curator in the creation of art? What work/exhibition needs a curatorial process, and are there limitations?

J

The relationship between fine arts exhibition and curating has become such a tradition that it is no longer argued whether an exhibition must be curated or not. The basic idea is based on the belief that the values of fine arts lies in the realm of thought, and knowledgeable experience is needed to interpret these values. If the artist or artists believe they have the ability to do this themselves, then they do not need a curator and their exhibition does not need to be curated.

The advent of the independent curator has added a new dimension to curating. The emergence of the profession is inseparable from contemporary art developments which were triggered by triggered by cultural criticism in the 1980s which essentially was a critical position taken by the public, who felt that they were not included in the discussion of cultural values. At the time, what was discussed by the museum curators were absolute values based on art history that mirrored the museum’s collection. Independent curators took a different position. Along with artists, they immersed themselves in society and searched for cultural values that were actual. This was when communicating with society, exhibition presentations, policies provoking impact became important matters. The collaboration between artists and curators in creating exhibitions included these things.

H

How did you see the advancement of curator in Indonesia?

J

It’s exhilarating. In a study of curatorial practice in South East Asia held by the Japan Foundation, it was revealed that the number of Indonesian curators exceeded the number of curators in every other nation of this region. Our curatorial process also gains its praise with their mindful approach to the art piece, compared to the curatorial process in other nation working under certain art organizer and only responsible for the presentation of an exhibition.

It is noteworthy because we don’t have any formal education about curating in the country with the absence of art historian as a subject that digs up on art theories, which produce qualified art critics, curators, historian, and gallery owners as the output. People who are interested in becoming curators are the one that are interested in the philosophy and the theory of art, and they study about this matter autodidact. Now, there are certain art institutes that are open to the idea of adding curating as a subject. Some of the Indonesian curators are the graduates of those institutes.

H

How do you see the journal/publication about art critics in Indonesia?

J

I admit that I heard a lot of comment regarding the decline of art criticism in Indonesia which results in a vague future for our art world. We have to understand that the definition of curator and art critic is quite different. Critics write their commentary after seeing an exhibition, and curator writes the preface to an exhibition after spending months assisting artist to prepare the exhibition. What happens now is that the definition of that profession are often overlapping each other, making the concept became blurry.

Attending the 1997’s press conference of International Association of Art Critics (IAA) in Tokyo, Japan, the line between art critics and curator are questioned by Japanese curators, who hold tight to the definition of each profession by committing not to write art criticism in the mass media. They asked about whether it’s ethical if they enlist as the member of the art critic association. In that conference, it was concluded that it was possible for them to be a member of IAA. The conference also confirmed that curatorial writing on an exhibition catalog could be interpreted as art criticism.

The declining role of art critics is happening all over the world, consecutively with the existence of contemporary art. Generally speaking, the idea of art criticism as an evaluation of qualification is renewed with the concept of an extraction of values and the socialization from an art piece. The development of curating also drives people to look more into the depth writing of curatorial explanation. The short reviews of an exhibition that are published on mass media are not considered as credible ones. I think it is a fact that every art critic should understand. Instead of competing the quality of curatorial explanation, I think it is more important for them to write better art reviews that are beneficial to the public who cannot go to the exhibition.

H

You wrote the book titled “Indonesian Modern Art and Beyond” on 1997, do you see any advancement in the art world of Indonesia? And is it possible for us to get the sequel to that book?

J

I wrote that book with the support of Yayasan Seni Rupa Indonesia to equip the participation of Indonesia in an exhibition by World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland in 1997. That book contains a brief explanation of the development of art in Indonesia from the era of colonialism to its progress until late 90’s.

Looking at it now, I can say that the book is not that good. The editing in Bahasa is terrible due to the lack of quality by its editor. The distribution was not great as well. The writing only covers the development of art without any significant explanation regarding the theory of art history because I was reluctant to write about it back then. I do write about the emergence of contemporary art in that book (beyond modern art), something that correspondently related to its rise in Asia. We can see that the emergence from that era is related to what happens now.

If only I wrote it better, I could follow it up with details of the development of art in Indonesia. Unfortunately, the book is poor in quality, so the penalty for me is to write a new book about Indonesian art in a whole different perspective. After 20 years of my experience, a lot changed in my way of thinking, my hesitation is thinning out. I hope it is a positive vibe.

H

What do you think would be the positive step to create a better atmosphere in the Indonesian art world?

J

I agree with the popular perspective regarding the importance of infrastructure refinement. I don’t think the problem rely on the institutionalization of that infrastructure though. I like to think it as a mechanism of the shifting of values. This mechanism is an exercise to raise the level of common perspective regarding simple things in daily life that will build a better solution for the bigger problems.

I can mention to you two level of perspectives. The first one is praxis, where reality is seen from its literal meaning. Reality is seen as “particular” with its practical function.

The higher level of perspective exist to a metaphysical degree where reality is seen as “universal”. Here, reality loses its material trait as well as its practical role and specific nature. This level of thought features the awareness of values, conscience, spirit, goodness, positive minds, and common sense. The shifting values of the art infrastructure exist on this state of perspective. This is why the metaphysical perspective shows the character of art such as sensibility, compassion, the charm of a beauty, contemplation and enlightenment.

The rapid commodification of art pieces that happens now shows the misconception of that perspective. The existence of insignificant issues that are unrelated to the art world like the application of the market mechanism in the art trade and fake paintings are some of the examples. There must be something wrong when the painting that has a million dollar price tag doesn’t have a clear intrinsic value. This kind of incident is forced to be interpreted as a sane phenomenon in the art world for the public. Where the fact is that common sense is not something that you can force, and public could feel it.

On a larger scale, we just saw the national public debate where laws, politics, constitution and even human rights lose its philosophical trait and viewed on the level of “particular” perspective. We could feel how personal interests are penetrating public interest, and we also could see that our social ethic, moral sense, sensitivity, and our modesty are agitated. This is what happens when irrational things are forced to be understood as natural matters. Another proof that you can’t shape the common sense of the public.

H

Do you have any interesting story regarding your experience as the curator of Galeri Nasional?

J

Since its opening in the year of 2000 until now, I have never become the curator of Galeri Nasional. I did this because Galeri Nasional was born from my idea and I don’t want people think that I proposed the idea so that I could become the curator of this institution. This issue spread widely among the art scene that time. But I do have interesting stories about my experience with Galeri Nasional.

Galeri Nasional was born by the time Prof. Edi Sedyawati officiated as the General Director of Indonesian Culture. She served wholeheartedly during her tenure, she really put all of her thought into the development of the nation’s culture, though with the very limited budget that was given at the time. During that period, the general director, that also known as a dancer, relied more on her artist friends than she did on the official personnel – I was one of her friends. This was her way to initiate many cultural institutions with that limited budget. Galeri Nasional is one of the results of this movement.

Ms. Edi applied an academic paper about Galeri Nasional to the minister of Administrative Reform on 1996 and she persisted about this idea through the intricate process. It took three years and with the help from the Ministry of Education and Culture as well as other departments, the mission finally worked when Galeri Nasional was inaugurated in 2000. There was a problem still, when it finally opened, it was installed as a third echelon institute that had a very limited budget. To help it become a more independent institution, the Administrative Reform Ministry changed the status, becaming a self-help foundation, with a promise to upgrade the status into the second echelon (the same level as Museum Nasional) that has a better budget allocation.

To support the condition of Galeri Nasional at that time, me and Ms. Edi tried getting support from private organizations, galleries, and funded artist to become the sponsor of Galeri Nasional’s exhibition programs. We did give them the freedom to sell their artworks, but we asked them to do that transaction after the exhibition ends. We’re also very concerned about the quality of the exhibitions; this is why we established the curatorial team for Galeri Nasional. I personally asked the curatorial team to curate the exhibition proposals without any reward, fortunately, all of the curatorial are willing to do so.

The output from that program is our achievement in holding big scaled-to international exhibitions in the gallery. Galeri Nasional became the barometer for Indonesian artists as well as the art world itself. The international public sees Galeri Nasional as a “real” gallery with a “real” budget, nobody’s going to believe that Galeri Nasional was receiving greater financial support from the community rather than from government despite the fact that it is a state institution.

Last year, under the command of Mr. Katjung Maridjan as the current General Director of Culture, there was a raise on the allocated budget for Galeri Nasional. I proposed an academic paper regarding the echelon status of Galeri Nasional. I heard the currently postponed decision about it has already been approved by Mr. Anis Baswedan, the current minister of education, and is in progress to get submitted to the Minister of Administrative Reform. We’re really glad to hear this news.

H

About the “Aku Diponegoro” exhibition, can you tell us about the background story behind it?

J

When they asked for my help as a curator, I thought that this exhibition was a sequel to the Raden Saleh’s exhibition in 2012 – It was not. Goethe Institut decided to display an exhibition about the capture of the Prince because Raden Saleh piece about it just got restored with help from them. You need to ask for Goethe Institut about the actual information about this.

H

What is the vision of the involvement of cross-generation artist-including contemporary artist on Aku Diponegoro exhibition?

J

At first, our plan on the curatorial position was to capture the continuous emergence of Prince Diponegoro in the development of Indonesian art world that convey the history side of it. But after the research, we couldn’t confirm it because we found out that the emergence of the image is discontinuous.

The early emergence of Diponegoro’s images appear on war posters and paintings from 1946-1949. We couldn’t find the specific reason why the image of Diponegoro looming as the icon of the battle against colonialism. The only available knowledge is that The Java War that was led by Diponegoro cost the Dutch a lot in that era of colonialism. Looking back at the Diponegoro painting by Raden Saleh in the 19th century and another appearance later in 20th century, this kind of circumstance continues to happen even after the declaration of independence. This phenomenon attracts historian to dig about it more. The question regarding the existence of the continuing appearance of Diponegoro as the icon of the Indonesian history arose.

But it also appears that the emergence of Diponegoro as an icon has another mission. By promoting the rebels of colonialism as the national hero, the nation is marking its territory as a post-colonial country, where its region equivalent with the colonies’. Paintings of Diponegoro after Independence Day shows this intention. Here, we can see the discontinuity of why Diponegoro became the icon in the era of 1946-1949.

The discussion about Diponegoro appears once again when the painting of Diponegoro’s arrest by Raden Saleh returned from the Dutch Kingdom in 1979. The return of this painting rebounds the historical aspect about Diponegoro aside from the mission mentioned earlier. A study once more showed the inconsistent imagery of Diponegoro as a historical icon.

The historical study shows a new awareness of the country’s narration that never been discussed before. It generates a new dimension of the study regarding the struggle of Diponegoro – the international dimension. Diponegoro’s resistance is one example of social upheaval among many similar happenings in Europe and its colonies in the 19th century. Those upheavals show an early consciousness of social justice and democracy worldwide. Indonesian history cannot be separated from the history of the world. The contemporary artists that participated in this exhibition are young artists that already showed their presence on global development and demonstrated their passion for reading those signs because they aware of their history.

H

One of the highlights of Aku Diponegoro’s exhibition is Raden Saleh’s painting, how significant is this painting among his other paintings?

J

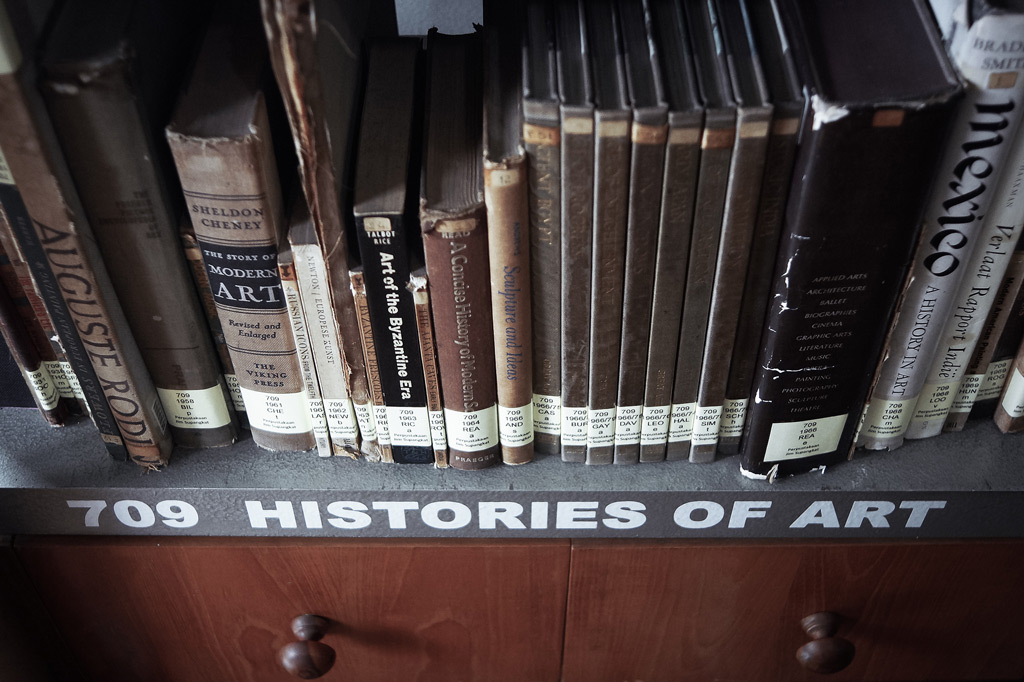

On the new awareness of the nation’s narration that I mention earlier, tucked an attention toward the development of our art advancement, and of course Raden Saleh’s piece has a central stand on this matter. In an analysis of our country’s art culture development, it shows that Raden Saleh’s painting contains a lot of key aspects, not only for the development of Indonesian’s art scene, but also for the world.

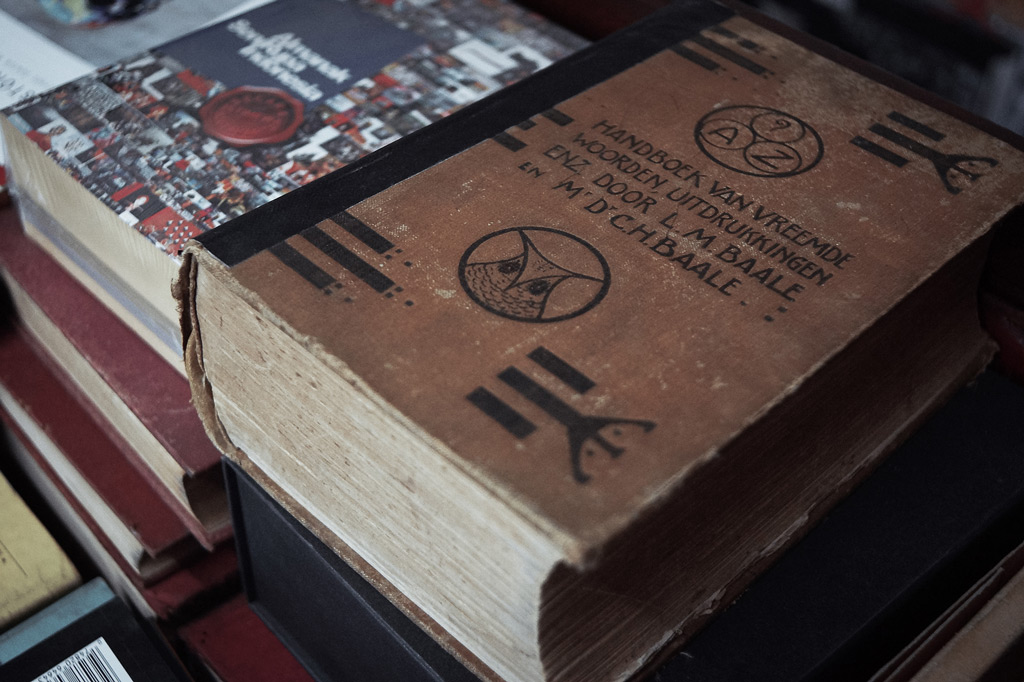

I stated on my previously released art journals that the socio-politic dimension of Raden Saleh’s depiction of Diponegoro’s arrest can be seen as a fundamental reason why the tradition of art making originated in the west, then adapted in the east. The signs of Raden Saleh’s painting shows that the adaptation in the 19th century is on a socio-political level. The art-making adaptation is a part of the growth of a modern perspective that lead the colonies to begin their movement toward independence and democracy in the early 20th century.

The adaptation doesn’t have to be a plagiarism of the blueprint, the adaptation is a parallel symptom that coincided all around the world in the 19th century. Just like what I’ve said earlier, during that century, there were a lot of social upheaval in Europe and its colonies. The Diponegoro’s war and Padri war in Sumatra that happened before can be classified in the same category as the upheavals that happened in Europe. Its local scope is about the same with the phenomenon happening in Europe including the two French Revolution.

Raden Saleh lived among the elites. Sovereignty and feudalism belonged to elite intellectuals who ideologically justified public uprising just like GWF Hegel, Auguste Comte, Karl Marx, or John Stuart Mill. This attitude can be seen in his painting of Diponegoro as well as in his other paintings. The foundation of this character can be traced back to Hegel’s idea in the early 19th century that did not see the existence of mutual relations between slave and master, which can be interpreted as the relationship between the colonialists and the colonists.

This understanding help us interpret other works by Raden Saleh. His adaptation of art making from the west did not show definitive signs of acculturation as it portrayed the romanticism that was developing in Europe. We also find other new messages in Raden Saleh’s pieces. We all know that Raden Saleh paints a lot of wild animal hunting. He always illustrates the hunting as a war between the hunters and the wild animals. We can perceive this as a symbol of the clash between colonialist and its colonies. He also draws a lot of brawls between tigers and bulls, and fatal encounters of human against wild animals. It symbolizes the dispute of powers in life and death struggles. The imagination built with art sensitivity regarding the history of Indonesia turned into the nation’s socio-politic reality in the early of 20th century.

H

Peter Carey stated that the display of historical artifacts of Prince Diponegoro are troubled with some sacred items that cannot be moved to the Galeri Nasional-which happens a lot in this country. Do you have any comment regarding this phenomenon in relation to the awareness of Indonesians to the essence of archiving?

J

I believe this refers to Prince Diponegoro’s cape, which was unable to be displayed in the exhibition and has become a hot topic on social media. I am of course disappointed with the cancellation. The concern of the cape’s safety in the exhibition is totally unreasonable. The team of Aku Diponegoro exhibition consists of Susanne Erhards, an art conservator from Germany, and Peter Carey, two of the most competent people in handling Diponegoro’s cape. Not only do they guarantee the safe transport from Magelang to Galeri Nasional, they also provided expert advice in order to keep the valuable artifact in shape.

The failure to display the cape making the museum fail its function to present its historical collection to the public. But what can I say? There is a possibility that the museum administrator did not understand their responsibilities well. I also agree with you that this kind of thing happens a lot in our museums and archiving sites. But I don’t want to stick to this kind of issue, it’s frustrating. I prefer to discuss more about how this kind of thing happens and how to put an end to it.

As we all know, museums play a central role as a cultural infrastructure, which includes regional museums, national museums, national galleries, national library to historical sites around the country. It is the responsibility for the government to manage it. I need to clarify that these institutes I’m referring to are state institutions, not the government agencies. So it is the state’s duty to put some kind of natural cultural policy that are arranged by experts, just like in developed countries. On this policy, we can define many details about how to operate the museum on a right way so that the administrators understands their duty and responsibilities to the public.

As far as I know, this country never had such cultural policies. They might oversee its essence. But it is also possible that our artists turn down the idea. Perhaps it is because it isn’t well thought out, or perhaps because it is the apprehension of the artists. We afraid that the policy will put restrictions for the artist and public, it is a big threat specifically to the artists who afraid to lose their freedom. I believe this is myth and paranoia.

This tension regarding cultural policies made us omit the importance of this policies to manage those cultural institutes. So that we neglect the need to demand such responsibilities from the government to regulate it.

Of course, this national cultural policy has to envision putting certain programs in the country’s cultural infrastructure. These programs also need to spur the values of culture and art in the infrastructure. There’s no such thing as being late to start on something positive and we can put our efforts firstly on our existing international institutes like the National Library, National Museum, and Galeri Nasional. Now, the National Library is managed by the state secretariat, National Museum and Galeri Nasional is under the Ministry of Culture and Basic Education, I think those three institutes will perform better under one ministry: the Ministry of Culture and Basic Education that is competent to construct the national cultural policy.

National Museum is an ideal medium to introduce the geo-history of Indonesia as the concept of “Nusa-Antara” as well as the “Indos-Nesos” theory. Its 150,000-artifact collection shows the heritage of the nation. Meanwhile, Galeri Nasional is a tool to question the history of the Republic of Indonesia, because they do have a collection that reflects the country’s past. “Aku Diponegoro” as an exhibition that showed the early sign of a spirit of an independent nation is a proper example of a Galeri Nasional exhibition.

It is important to set national priorities so that those three institutes are able to create a wider impact, not only on the culture and art departments. We can see how we’re lacking these priorities when we failed to display Diponegoro’s cape. The inability is also reflected on how schools failed to build a clear picture of the origin history of Indonesia.