Jakarta and the Arts with Indra Ameng

Our Editorial Team (W) Visits Indra Ameng (A) at Ruang Rupa

by wjournal

W

Can you tell us a little bit about your background before Ruang Rupa?

A

I studied in Institut Kesenian Jakarta (IKJ) from the year of 1993 to 1998, studying graphic design at first. There, I felt I had entered a new world – the world of art, and decided I want to be immersed in it and make a living out of it. During my times in IKJ, the various faculties, such as film, theatre, music, were all closely related, so we were exposed to different activities. The fine arts kids work in theater, help the film department or organizing music events. The exposure to different skills and mediums resulted in me not working strictly in the area of fine arts.

W

Is there a particular reason why you were interested in the arts?

A

I’ve been interested in the arts since I was very young. I remember while I was still in primary school I was asked what I would like to be when I grew up, and I always answered “I’m going to be an artist.”

W

What is this interest you had since you were young like?

A

It’s like this. I use my art background to approach every subject. Even if it is work in a different field I will approach it with that sense… analyzing everything from a visual perspective before anything else.

W

Did this perspective form when you studied in IKJ or since you were young?

A

I believe it was from a young age, but when I was in IKJ, the environment enriched that sense – I learned a lot from my friends and my seniors really influenced me.

W

So how did you get involved with Ruang Rupa?

A

After graduating I worked in a production house with some of my friends, making videos and all sort of stuff. Since most of the friends from Ruang Rupa were actually my university friends, we were already close and have worked together many times, so they invited me to join in one of their projects.

Ruang Rupa started in 2000, and in 2001 I was asked to be the project officer of a Jakarta Habitus Public, a public art project which was a part of Jak Art Festival in 2001. The project involved inviting approximately 70 artists to create art in a public space. As time progressed I kept on being invited to join various projects and finally I just decided that I belong here.

W

Is Ruang Rupa vision similar to yours or are you actually adapting your vision to Ruang Rupa?

A

We always had the same vision, there was a need for a space like this, this kind of space didn’t really exist back then – arts initiative, arts space that could accommodate the young artists or alternative art talking about new things that are related to visual culture. One of the effects of 98’ [the beginning of the Reformation Era] was this flood of ideas, people wanted to express themselves, Ruang Rupa gained momentum from this.

W

Is Ruang Rupa’s growth part of its initial vision or was it more of an organic growth?

A

Our initial vision was to make a space. Ruang Rupa emphasized one the word space [Ruang]. It began with talking about a space to accommodate alternative art, a meeting point for young artists to talk about the city.

W

Why are you focused on urban environment?

A

Because we are based in Jakarta and the city is the first thing we see. Urban problems are a part of our daily lives – even walking down sidewalks there are warungs and and other obstacles in your way. Here [Ruang Rupa] we talk about urban development through the arts. We use fine arts to see and communicate and to develop projects. Most importantly it serves as a space to support young artists that wouldn’t have a place to express themselves otherwise, an [art] laboratorium of sorts.

W

How was it like for Jakarta artists before 98’?

A

In my opinion, many strong institutions that previously supported many activities became stagnant. Also, most galleries are commercial in nature, so there weren’t places to accommodate new ideas.

There was a lot of potential, there just wasn’t any place to channel it. Places were either too commercial or conservative, resulting in progressive and critical ideas having to compromise. Either they compromise by being conservative, or compromise in being commercial, either way the idea becomes impotent.

W

So what happened to them then before Ruang Rupa?

A

If they were still studying in a university, that’s where they would exhibit. After that, they usually go work in some industry.

Oh another thing, we [Ruang Rupa] feel that Jakarta has the potential to be able to build its own character and gain more recognition, like Yogyakarta and Bandung.

W

What would you say is the character of Jakarta art?

A

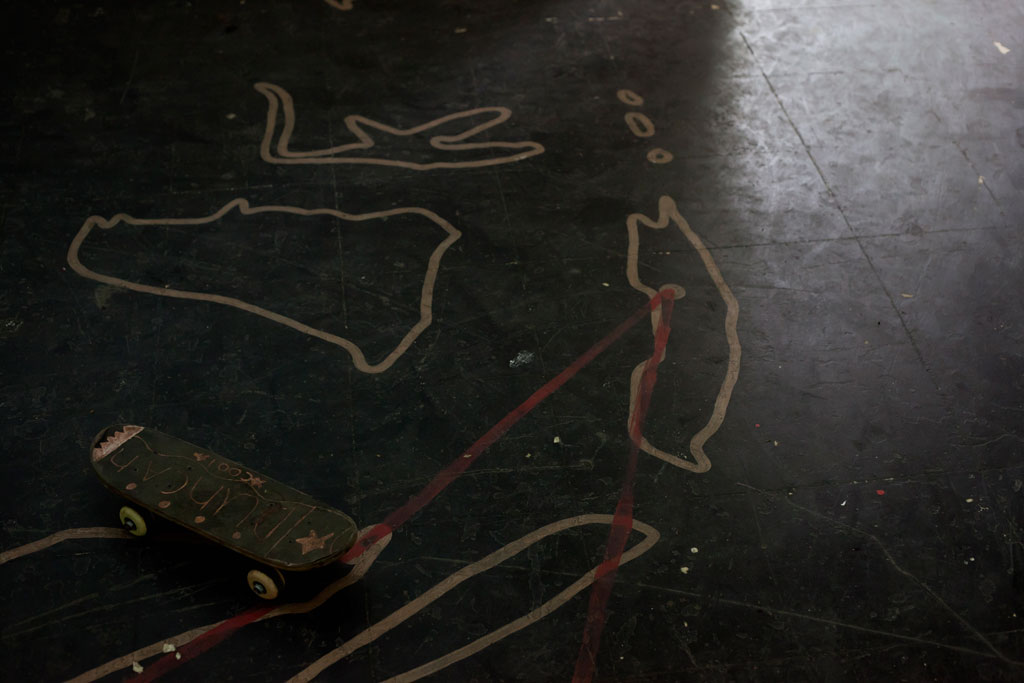

If we talk about Jakarta, the work can be considered rough, brutal, straightforward, raw and it’s fast. Here [Jakarta] you need speed, everything is instant – from how you work it out as there is no time. Time is of an essence in Jakarta. The art is very responsive, and it tends to be expressed in a raw and explicit fashion. Of course we shouldn’t generalize, but this is one of Jakarta’s tendencies.

W

Looking at the year of 2010 and onwards, how is Jakarta arts scene? Has it been growing? What phase is it in right now?

A

The way I see it, right now what’s exciting is the fact that there are many ‘pockets’ of new spaces, communities and group of artists coming up, and it is great because now we have new friends that work in the same field bringing their own individual approach and ideologies. They work in different fields such film, photography, and street art, but in a larger perspective they are all social commentaries – creating discussion, building ideas, criticizing.This also creates a healthy competition and a fun one, because now artists must be more active and innovative to get their work recognized.

W

You personally have made various music videos and photography. Why did you choose those media? Did you explore other kinds of media?

A

Although in university I began studying graphic design, print to be exact, I also collaborated with students from the film department, and at the same time there were good bands that came up in Jakarta’s music scene back then, so we made their music video.

In terms of photography, I think that fine arts students, such as myself, are naturally drawn to photography. As a photographer, I see myself as an observer, and photography is the perfect medium to document our observations.

W

How were you involved in music at the first place? Have you ever been in a band?

A

I can’t play music at all.

W

No at all? Not even singing?

A

No, I can’t, well… maybe I can sing. Music is something that I like, that I enjoy, but I have no wish to be a performer. If I was to be involved in creating music, I will perhaps be in a studio, but not as the musician.

I began really enjoying music when I was in college, so in the 90s I organized gigs at venues such as Poster and on campus. The music scene was really vibrant, and during that time I was asked by my friends in a band called Rumah Sakit to be their manager. And from that I plunged into the music scene.

During that time I was also involved in helping out a design company called Satellite of Love. They did a lot of album covers. And after that I started helping make music videos. Although I was much more involved as a producer rather than a director.

I feel that music is more liquid compared to fine arts. I think fine arts has always been considered complicated or heavier. Fine arts gives the impression of being difficult, and music is more accessible. That accessibility is something that Ruang Rupa is trying to develop, to make art something that is relatable, that is part of regular life.

W

I agree that fine arts can seem intimidating at times because it has this image of being difficult to understand…

A

That’s right. There is this distance that is built between the art and the audience. It’s difficult, to the public it seems inaccessible, especially using language and terms that are difficult!

W

The impression is that only people who study art can enjoy art

A

Exactly.

W

You are a very visual person. How important is the relationship between visual and music do you think?

A

I think it is very important. Ok, of course the music comes first, but what people will remember is the image. How Iron Maiden is visually associated with…or David Bowie – people will remember their image, so it is important to create visuals that represents the music and it’s attitude. It [visual] just cannot be separated.

W

When you manage a band like White Shoes & The Couple Company, where does the visual direction come from? Is it from you or from the artists themselves?

A

It comes from the group, I just give them some ideas and suggestion. The idea definitely comes from them first. I act merely as a facilitator, a mediator.

W

Then all these time, how many bands have you managed? Rumah Sakit and White Shoes and The Couple Company only?

A

Three, actually. There was one more a long time ago in 1993 or 1994. There was a band called Pepper Light. They covered The Cure, Smashing Pumpkins and other bands during that era. They tried composing and recording their own songs, but that didn’t really go anywhere. The band finally disbanded and I focused on Rumah Sakit until 2004. Only after that, I then joined White Shoes. With White Shoes, I was the one that offered myself to be their manager. It was different with Rumah Sakit where they asked me to.

W

What did you see in White Shoes that made you interested?

A

In the early 2000 I was very active in the music scene and very interested in the independent scene. I noticed that bands from the 90s and early 2000s, they are heavily influenced by foreign scenes… British, American, genres such as garage, or new wave. Then I suddenly heard White Shoes. I watched and listened, and I saw their reference was very Indonesian, and a very cool one at that.

They have a very strong Indonesian feel to them, and not many bands have achieved that. They aren’t the first to go retro, Naif presented that 60s imagery before, but what White Shoes captured was a unique in how they gathered their influences and produced their own sound. Also in terms of music, organizing gigs is addictive.

W

How is it addictive?

A

I don’t know, I just feel that it’s a type of work that is fun for me because we are creating an event that make a lot of people happy. That’s really it, it’s addictive for me.

W

Can you tell us a little bit about the Secret Agents [Indra Ameng & Keke]?

A

The Secret Agents was formed when Unkle 347 invited us to do an exhibition. During that time I was really into photography, and I knew that Keke was also into photography, plus we hung out in the same group and I really liked a lot of her photographs. From there, we did the exhibition [as the Secret Agents], and we were invited to do another exhibition, then another, and it just kept on going.

W

So before you organized music events you were a photography group?

A

Yes, that was before we started organizing music events. Organizing music started because we used to hang out at Parc or here [Ruang Rupa]. Here in Ruang Rupa when we have exhibitions we would have a band or a DJ at the opening – usually with Keke, Nasta, and Batman. There were shows at Parc and Keke made an event in West Pacific and I helped… it started from there.

Superbad was made because we missed the now defunct regular shows that Parc and similar venues used to host. We had to make Superbad a monthly gig because there will always be new and exciting bands that will perform, and it’s just fun to get together with friends, hang out with old friends while we watch bands we invited because we enjoy their sound.

W

So what is the Secret Agents now? Is it still a photography group?

A

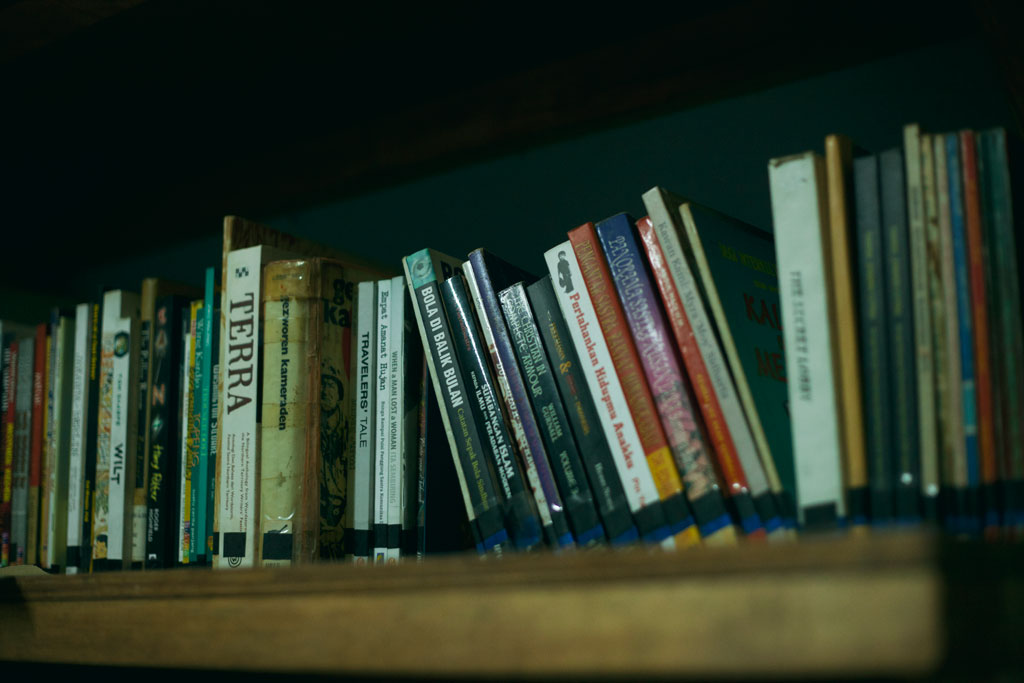

It still is. The current Secret Agents project is also making a book, but this one focuses more on Keke’s photography. Keke did a lot of music photography since the early 2000s. We hope this will be a good contribution, because we believe it is important to have a published documentation of the local music scene, particularly in Jakarta, Bandung, and Jogja.

W

Is there an image of Jakarta when it comes to music?

A

Yeah for me was what I experienced during IBIS, BIBIS, and PARC era. Those were the most memorable time for me, the 90s. But since there was no accessible recording of that period, it becomes hard to be inspired or referenced by kids nowadays.

W

You are Ruang Rupa’s Program Director and you are also an artist with your own body of work. How do you balance your personal projects with your work as a coordinator?

A

That is a dillema! On one hand, you want to support the program, the young artist – guiding them and acting as a facilitator/mediator for their artistic expression, but then you realize that this mediating is an art in itself. Sometimes the thought “ if you don’t stop, when will you have time for your personal work?” creeps up, and you just have to do it [personal work]. Sometimes here in Ruang Rupa we like to remind eachother “hey, it has been a while since you’ve created anything,” or “it’s been a while since we had an exhibition”.

W

Do you have any personal projects you are currently working on?

A

I am trying to make a book, archiving my previous work little by little.

W

Any idea as to when it will be finished?

A

I don’t know. I hope I can do it in this in one year.

W

So should we look forward to having an Indra Ameng book by the end of the year?

A

Yes, I hope so because I would like to archive my collection of photography into a book. Something that I envy is how abroad, almost all photographers have books of their works. There aren’t any photographers that cannot publish one, they can easily do that. Meanwhile in Indonesia, there aren’t many books about local photographers.

W

Why do you think it is so? Is it because there is no demand from the public or is it just difficult to create one?

A

I don’t quite understand either, perhaps it is a habit that has not been formed. We have to make it a convention. If photographers publish books it will eventually create a demand for it. Perhaps it is also because it is the digital age, everybody put their work online. I do believe the physical format is important, because it becomes an artifact. Without such documentation it is as if the artist never existed. The digital format is fast and immediate, as quickly forgotten as it is remembered, but an artifact occupying a physical space will always be there. Making a book is definitely one of my personal goals.