Cultural Identity and the Arts with FX Harsono

Athina Ibrahim (A) Interviews FX Harsono (F)

by Ken Jenie

A

We have read that your involvement in the art world started when you were in college. How did that begin?

F

Actually, it was too early to say my involvement started then, but I did start being serious with illustrating since I was a student in 1973. I only became part of a forum on fine arts by the end of 1974.

A

Did you have a certain motivation that made you want to be in the art word?

F

If we want to step back a bit, since high school I always had an interest in fine arts. I enjoyed painting and going to exhibitions. I lived in the small town of Blitar (East Java) where it was almost impossible to find anything about the arts. I think it just happened naturally. My enjoyment started from a hobby of being genuinely interested in what I did.

A

When did you see the opportunity to use your art as a tool for social commentary?

F

In 1972, there was a debate between Sudjojono (Sindoedarsono Soedjojono) and Usman Effendi. Usman Effendi made a statement claiming the non-existense of illustrative art forms, to which Sudjono disagreed. Since my college years, I have always questioned the issue of identity. My seniors have always closely placed identity with traditional culture. Tradition in this case wasn’t the adaptation of tradition towards the time. It was a visual culture, how it became infused in the artists’ artwork. The argument raised the question to whether Bali, Java, or Sumartra can represent Indonesia. It became an ongoing discussion where more often would lead to these artists talking about past issues without presenting it in the context of the present time.

From those discussions between four to five people, there was a refusal to use tradition as a tool to define identity. We had to find a different theme. And we realized the political issues in Indonesia, wherever we were — no matter which part of the city we were in — were the same. Every one of us were facing Soeharto’s regime where conditions were repressive and democracy did not exist. We understood that political conditions were a representation of people’s situation and their time. We decided then on that social themes were something we wanted to focus on.

A

Is that when you formed Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru (New Art Movement)?

F

Yes, it was in 1975.

A

We read in an article that you formed Gerakan Seni Rupa because the art during that time was influenced greatly by Western culture. Do you feel this is what is happening now as well?

F

It wasn’t exactly influenced by Western culture. During that time, there was a big idea that was widely accepted by society and they called it Modernism. So artists at the time were constantly aiming to make something universal to be accepted in the international forum. If we always apply our art form with Western concepts or mainstream forms of art such as paintings, sculptures, graphics, which are known as Fine Arts, then it is unavoidable to have our work always be critiqued to be part of a Western way of thinking — whether it is abstract, impressionism, or expressionism. This is what is called Modernism, the great concepts that evolve from the West and the Third World were often proclaimed to be a follower of the West. Which is why as a movement we decided to not make any artwork on a medium which were defined as Western art, neither painting, sculpting, nor graphic. So we made anything, anything we found could represent the social theme we highlighted and we gathered it to make a completely new art. Since our approach was new, we called it the Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru (New Art Movement). Sudjojono believes that our hands are a seismograph needle that can expose our emotions. Even the modernist way of thinking believes that an artwork can only be unique because of the emotions put into the art, how our mood today can be different from tomorrow.

A

So where did the exploration of questioning your own identity evolve from?

F

Since 1985, I have been active in various non-governmental organizations. I was known at the time as an activist artist involved in social commentary, but my intention was only to highlight those who were victims of the political turmoil.

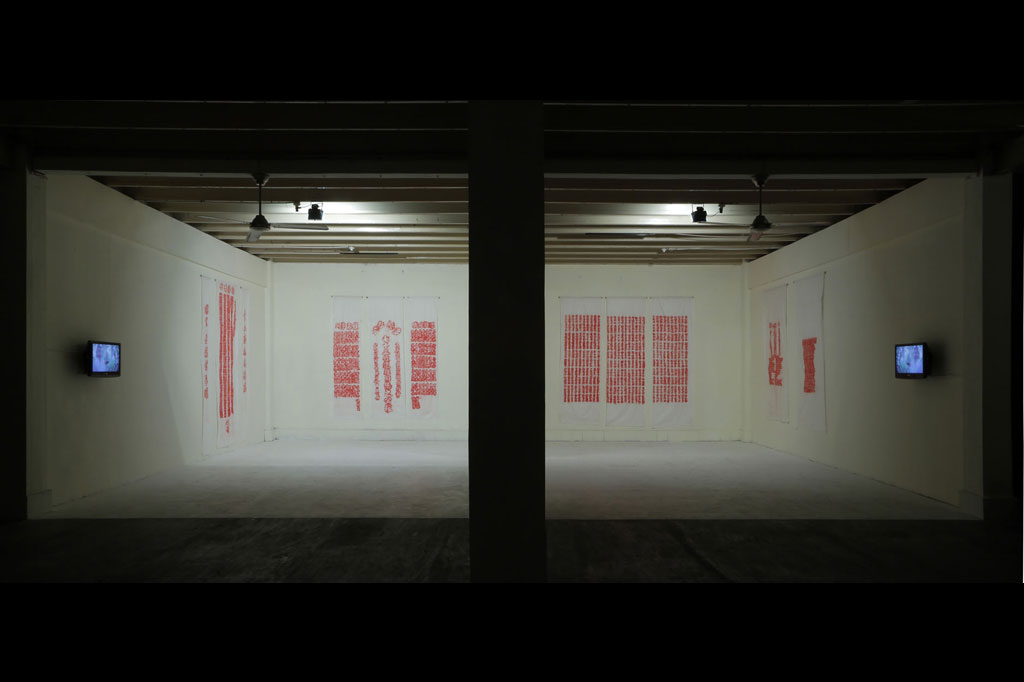

After 1998, I was still raising social issues of what happened during May 1998. The political situation after 1998 took a different turn. More people had the courage to voice their opinions and critique the government system. This was a tremendous change in our society. I was sure this change would lead to greater change in our culture. I started questioning the artwork I was making? Did I want to keep making artwork that critique our government? This is when I started questioning my own identity. Who am I?

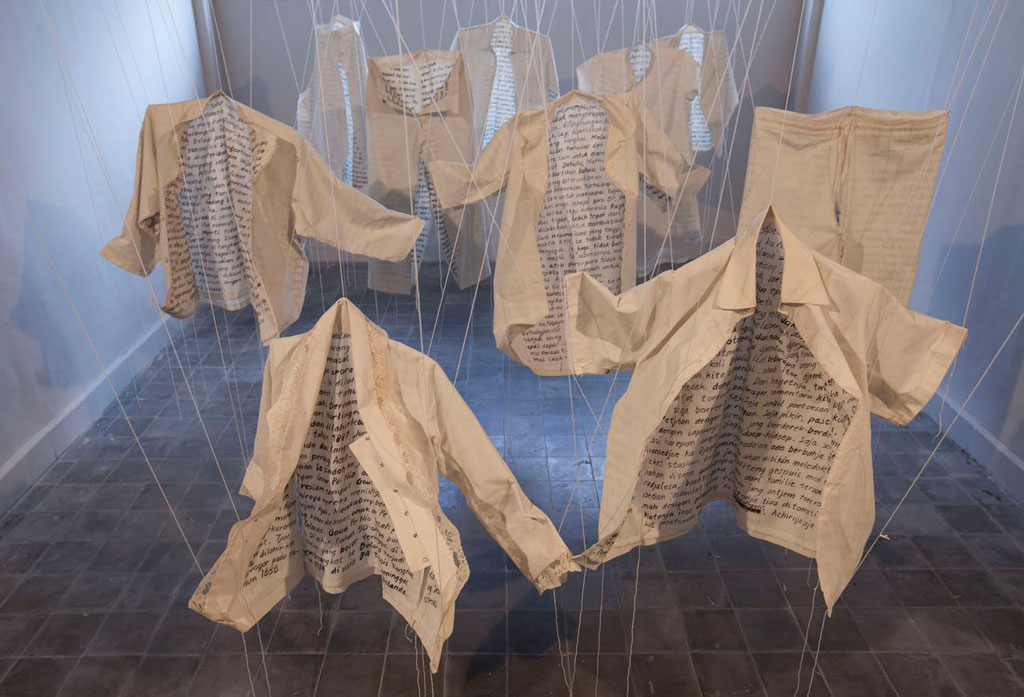

When I started breaking down those questions, I realized I was a person of Tiong-hoa descent who has little understanding of Java or even my Chinese background. I wanted to do something about it. So I started looking into my own history, which was impossible to find in the culture that surrounds me. When I traced back my own history, I ended up finding about a lot of different issues relating to discrimination or issues which had no relevancy to who I was.

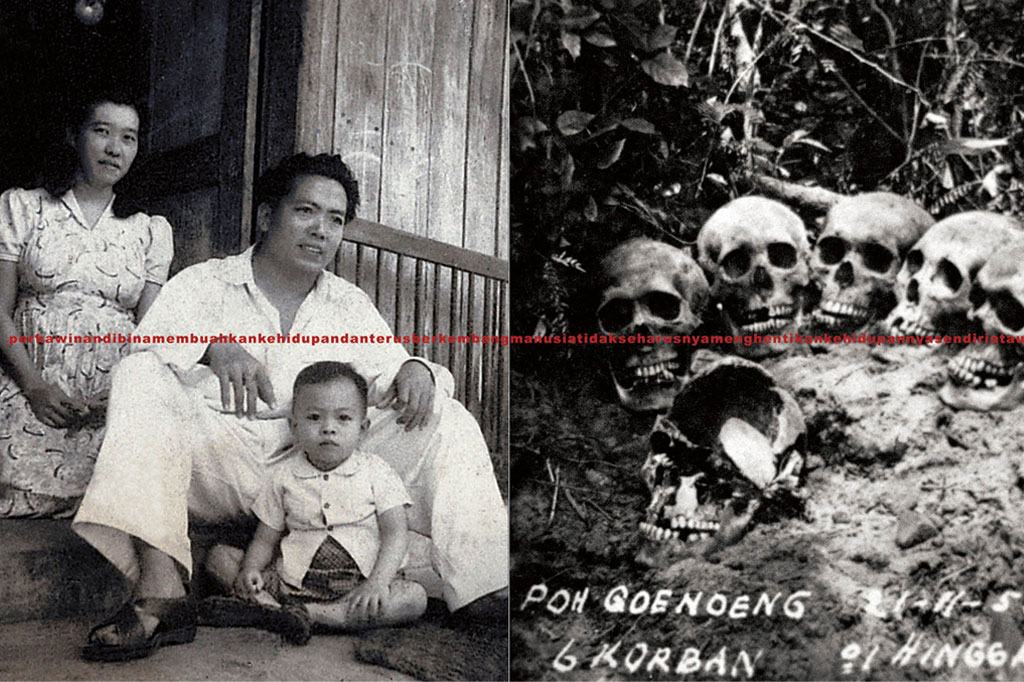

I started then to evaluate my family’s history. I am probably the 6th generation of Tiong- Hoa descent, but if I had to trace my own family tree in search of information of my great grandparents, I probably would not find anything. Instead I started from my parents and the people closest to me. I started observing what they did, and questioning who they were. I ended up finding remarkable discoveries. My dad was a photographer, he has a studio to take passport photos, but I found out in 1951 since he had a camera, he was responsible in documenting the excavation of Tiong-Hoa people who were killed in 1949. I started then to dig deeper into this issue by reading and researching before I decided to make my artwork.

Through my research process and the latest exhibition, I understood that our history is written by the winners. And those who lose do not have a voice or a place in history. History will always be presented by those supporting the power of those who reign. From this I concluded that history is not singular, there are little parts of history of my own history or the history of my community and the rest.

A

How do you promote that sense of curiosity to want to understand our own history?

F

The problem is our education does not promote the study of history with much importance. This is a huge disadvantage. How can we appreciate if we do not know anything about our roots? How can we appreciate our culture if we have no understanding about what local culture is.

Here, schools have the capability to become a motivator for students to be interested in history. We know for a fact that from elementary school to highschool, history was only meant to be memorized. Behind all these historical records, we should always asks questions about what truly happened.

A

Do you think we have become a comfortable generation, having an endless amount of information constantly fed to us at a quick pace?

F

I wouldn’t say we’re comfortable, we are just in a culture where the media values something more entertaining. The question is not whether we are comfortable but why are we complacent? Often it is because our culture does not encourage students to be critical with their thought process.

This is one of the reasons why we in Dia.Lo.Gue created EXI(S)T, we try to promote a forum to assist young artists to see an issue critically, whether it is an issue that relates to them personally or if it exists externally in society.

A

In talking about EXI(S)T, why did the team decide to focus on highlighting young artists in Jakarta? Knowing that Bandung and Yogyakarta has made its mark in the fine arts world.

F

In observing the reality of fine arts in Indonesia, we find most of the commercial art spaces are available in Jakarta. But when we ask the question of who in Jakarta can represent the fine art scene, there are sadly only a few which we can mention. There is probably less than ten people who can represent the scene. Students that graduate from Bandung, Yogyakarta, Surabaya normally fly to Jakarta to look for a job. And it keeps me curious to find out who amongst these students are actually producing their own artwork. The ironic thing is whenever there is an international curator in search for an artist in Indonesia, they would immediately fly to Yogyakarta.

From the first EXI(S)T that we made, I saw that artists who live and work in Jakarta have the potential to grow, but what we are trying to do is to help support these young artists to be able to make it on a national level. In Jakarta it really is difficult. In Yogyakarta, there are many small-scale galleries that can attract the attention of other great galleries to provide a space for the artist to grow.

Jakarta is different from Bandung or Yogyakarta. In Yogyakarta, once you graduate, you can decide to become a full-time artist. In Jakarta it doesn’t work that way. The living cost pushes them to work in the industry — either full-time or part-time — while making time to create something on their own. This is what we try to highlight. I am sure their thought-process is different to those who live in other cities.

A

Can you share to us the process of selecting the artists to be involved in the second EXI(S)T?

F

The second EXI(S)T was an open call. The requirements were young individuals of any background living in Jakarta that has not taken part of our local art scene. We had about 70 people who registered this year. Other than going through their art statement and interviewing the potential candidates, there is one point that we emphasize — that is seeing whether their work in their portfolio has the opportunity for growth and exploration. The aim of EXI(S)T is once they have exhibited their work with us, we will continue to monitor their progress in the future. For the next three years, we will evaluate their prospect and future artwork and hope they can be active on a national level.

A

Is there a larger vision that you have for these young artists?

F

I see a tendency for these young artists to orient their creation towards the market. They create to sell. I am not saying it is wrong to earn money but their objective is wrong. The market will only consider the final result of a creative process. The market will not care about the medium and technique the artist have used. If the orientation of the artists is only to sell, then the process of creation is something which is not taken into consideration at all. Neither research nor experiment will be important for them. If this continues, we only would be producing instant artists. Which is why we value the process involved instead.

A

As someone who have created your artwork on both a national level and international level, do you feel you have responsibility to promote Indonesia’s fine arts on a larger scale?

F

Without a doubt. Everyone who has access to the international level has to decide on an attitude whether to place Indonesia’s fine arts on a larger forum internationally. EXI(S)T has been exposed on various international media and this has been one of our efforts to help promote our art scene.

A

From your observation and experience, how do you think the world perceives Indonesia’s art scene at the moment?

F

If we look at the phenomenon and development of fine arts, we can see that Asia is currently becoming the central attention of the world. Currently the attractive countries in Southeast Asia are Thailand, Philippines, Indonesia, and we can also start seeing Singapore gaining more exposure. There aren’t too many young artists there but they are starting to make many excellent conceptual artwork. Indonesia, Thailand, and the Philippines excel in both the skills and conceptual mindset. On a broader scale in Asia, India, Japan, Korea, and China are already doing remarkably well.

This is what I am afraid of: If five years ahead Indonesia is still progressing as we are now, we will loose our place in the international scene. Since 2010, the market condition of fine arts in Indonesia is rather stagnant. Our young artists are becoming confused about the steps they should make since they were only answering to the demands of the market and when there isn’t any market demand, you see these artists losing their place and disappearing completely from the scene.

What is interesting here is there are young artists out there making conceptual work without paying attention to the market demands. They are very industrious and keep making their mark although unheard of. The question is how do we promote a generation after that? There needs to be a proper support to create a sustainable and progressive art scene.

www.fxharsono.com

Photography:

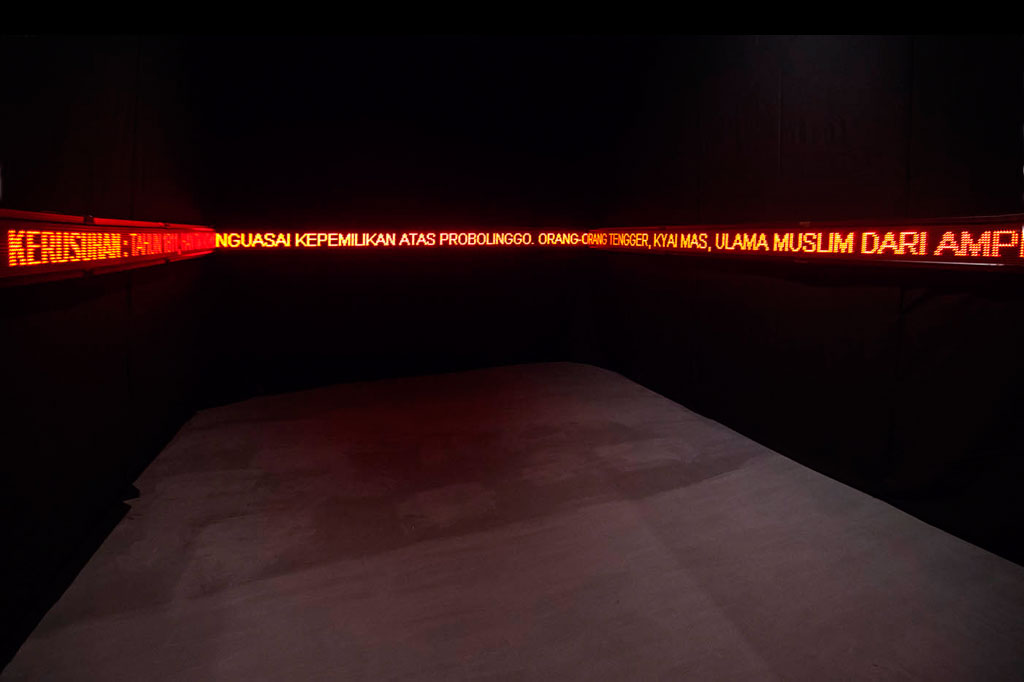

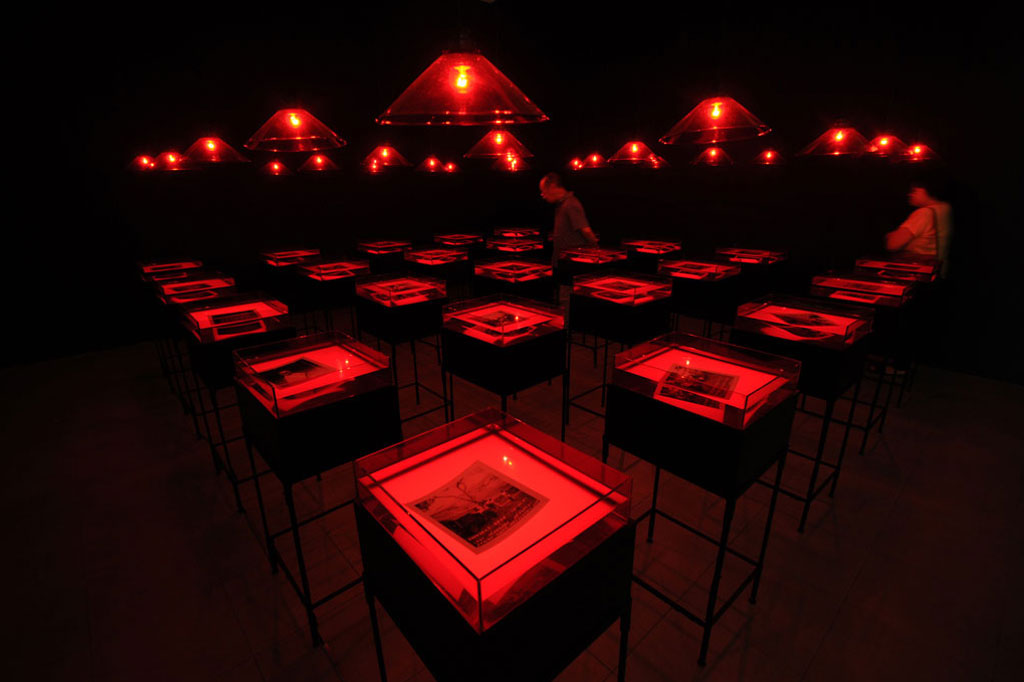

Dwiputri Pertiwi (1,5,10,14)

FX Harsono (2-3: Preserving Life, 4: Ziarah pada Sejarah, 6-7: Writing in the Rain, 8: Ranjang Hujan, 9: Dark Room, 11: Bon Apetit, 12: Sisi dalam Kehidupan, 13: Fear, 15: Menulis Ulang Pada Nisan, 16: Masa Lalu dari Masa Lalu Migrasi)