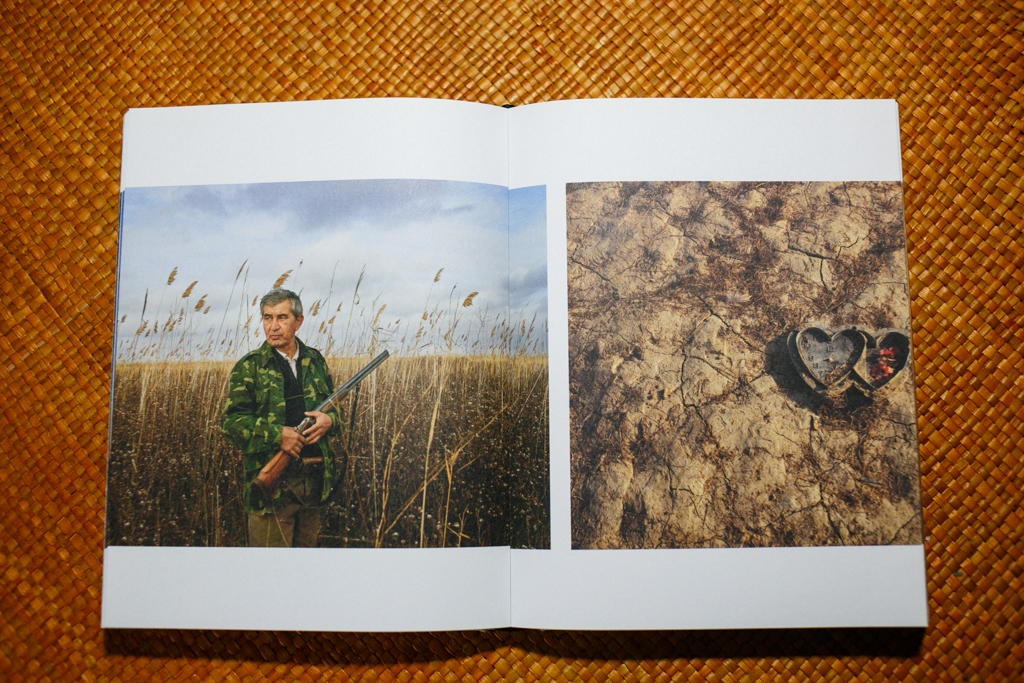

I reserved my last essay to an everlasting form of photographic publications: the photobook.

Let me start on what, to me, is a book. For me a book is not merely a collection of words on pages bound by a cover, nor it is merely a window to the world or a peek of the writer’s soul. A book is meant to be more than that – it is a legacy that is being left behind for future generations. It doesn’t only contain knowledge, but also memories as a reminder of what we have achieved.

What about the photobook?

The photobook could teach us few things; the first being history. A photograph contains visual information from a predetermined scene and time, where it allows the viewer to receive such information and literally take a glance at the past. Now a collection of photographs coupled with information would not only offer a glance of history but also a whole perspective.

As a photograph is also a projection of the photographers’ thoughts and experiences, it also becomes a work of art in the field of documentation. If we look at, let’s say, the works of Trent Parke in Minutes to Midnight, the whole work was actually conceived based on his road trip across Australia. Instead of offering a straight perspective of how the Australian landscape and its people are, Parke offered more than just field trip images. The selection of images and the editing process of those images allow the viewer to have a different view upon receiving the visual information contained within the book. This does not only allow information to flow through, but it also creates an understanding of Parke’s aesthetics and how he viewed his native land.

In Indonesia, based on the curatorial statements at the German, Japanese and Indonesian Photobook Show in 2014, it seems that although Indonesia has had a history of photobook publishing since the 1950, the revival of the Indonesian photobook only happened in 2008, where there was a sudden surge in the photobook production. The trend continued until 2013. One interesting thing from the development of the photobook in Indonesia is that the production, publication and distribution are becoming more independent (as in managed by the photographers themselves, such as Edy Purnomo, Rony Zakaria and Aji Susanto Anom). This has been achieved, of course, with the help of their Do-It- Yourself spirit, coupled with the help of social media and more affordable printing methods.

This trend is also influencing the number of books that are being published. Younger photographers, especially street photographers, look forward to publishing their work. Although this is good, I feel there should be another approach that photographers in Indonesia should take like, for example, documentation. Furthermore, there should be an understanding that publishing a book, although it has become much easier, is still an art in itself and like many other artworks, it can’t be done in an instant.

Unfortunately, the trend of producing and purchasing photobooks has not been capitalized by the major bookstores, nor has it become part of the local culture. People still find difficulties in getting the books that they want and most go to online dealers to get their books. It seems that local bookstores are clueless about what books Indonesians look for (hint: we don’t look for extended versions of manual books and another copy of Helmut Newton’s or any Big Book on Genitals). On the cultural side, people still do not understand the idea that a photobook could be given as a gift not only for themselves, but also to somebody else, as let’s say, for a wedding gift. If more and more people were doing this I am sure that in the future, Kinokuniya will not stock big books on genitals and Aksara will start to figure out that not all people are interested in Lomography.

To read the rest of the series, click the links below:

The Camera

The Photographers

The Photograph

The Editor

The Gallery